Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

July/August 1997 | Volume 48, Issue 4

Authors: Pauline Maier

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

July/August 1997 | Volume 48, Issue 4

John Adams thought Americans would commemorate their Independence Day on the second of July. Future generations, he confidently predicted, would remember July 2, 1776, as “the most memorable Epocha, in the History of America” and celebrate it as their “Day of Deliverance by solemn Acts of Devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with Shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more.”

His proposal, however odd it seems today, was perfectly reasonable when he made it in a letter to his wife, Abigail. On the previous day, July 2, 1776, the Second Continental Congress had finally resolved “That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.”

The thought that Americans might instead commemorate July 4, the day Congress adopted a “declaration on Independency” that he had helped prepare, did not apparently occur to Adams in 1776. The Declaration of Independence was one of those congressional statements that he later described as “dress and ornament rather than Body, Soul, or Substance,” a way of announcing to the world the fact of American independence, which was for Adams the thing worth celebrating.

In fact, holding our great national festival on the Fourth makes no sense at all—unless we are actually celebrating not just independence but the Declaration of Independence. And the declaration we celebrate, what Abraham Lincoln called “the charter of our liberties,” is a document whose meaning and function today are different from what they were in 1776. In short, during the nineteenth century the Declaration of Independence became not just a way of announcing and justifying the end of Britain’s power over the Thirteen Colonies and the emergence of the United States as an independent nation but a statement of principles to guide stable, established governments. Indeed, it came to usurp in fact if not in law a role that Americans normally delegated to bills of rights. How did that happen? And why?

According to notes kept by Thomas Jefferson, the Second Continental Congress did not discuss the resolution on independence when it was first proposed by Virginia’s Richard Henry Lee, on Friday, June 7, 1776, because it was “obliged to attend at that time to some other

John and Samuel Adams, along with others such as Virginia’s George Wythe, wanted Congress to declare independence right away and start negotiating foreign alliances and forming a more lasting confederation (which Lee also proposed). Others, including Pennsylvania’s James Wilson, Edward Rutledge of South Carolina, and Robert R. Livingston of New York, argued for delay. They noted that the delegates of several colonies, including Maryland, Pennsylvania, Delaware, New Jersey, and New York, had not been “impowered” by their home governments to vote for independence. If a vote was taken immediately, those delegates would have to “retire” from Congress, and their states might secede from the union, which would seriously weaken the Americans’ chance of realizing their independence. In the past, they said, members of Congress had followed the “wise & proper” policy of putting off major decisions “till the voice of the people drove us into it,” since “they were our power, & without them our declarations could nor be carried into effect.” Moreover, opinion on independence in the critical middle colonies was “fast ripening & in a short time,” they predicted, the people there would “join in the general voice of America.”

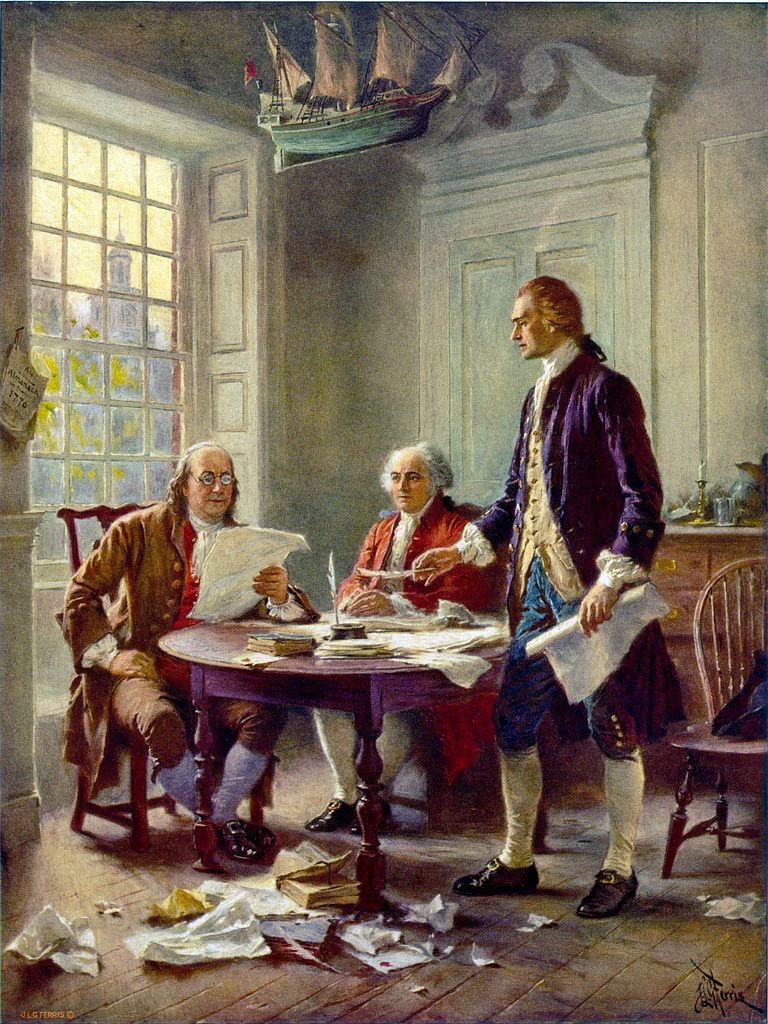

Congress decided to give the laggard colonies time and so delayed its decision for three weeks. But it also appointed a Committee of Five to draft a declaration of independence so that such a document could be issued quickly once Lee’s motion passed. The committee’s members included Jefferson, Livingston, John Adams, Roger Sherman of Connecticut, and Pennsylvania’s Benjamin Franklin. The drafting committee met, decided what the declaration should say and how it would be organized, then asked Jefferson to prepare a draft.

Meanwhile, Adams—who did more to win Congress’s consent to independence than any other delegate—worked feverishly to bring popular pressure on the governments of recalcitrant colonies so they would change the instructions issued to their congressional delegates. By June 28, when the Committee of Five submitted to Congress a draft declaration, only Maryland and New York had failed to allow their delegates to vote fo independence. That night, Maryland fell into line.

Even so, when the Committee of the Whole again took up Lee’s resolution, on July 1, only nine colonies voted in favor (the four New England states, New Jersey, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, and Georgia). South Carolina and Pennsylvania opposed the proposition, Delaware’s two delegates split,

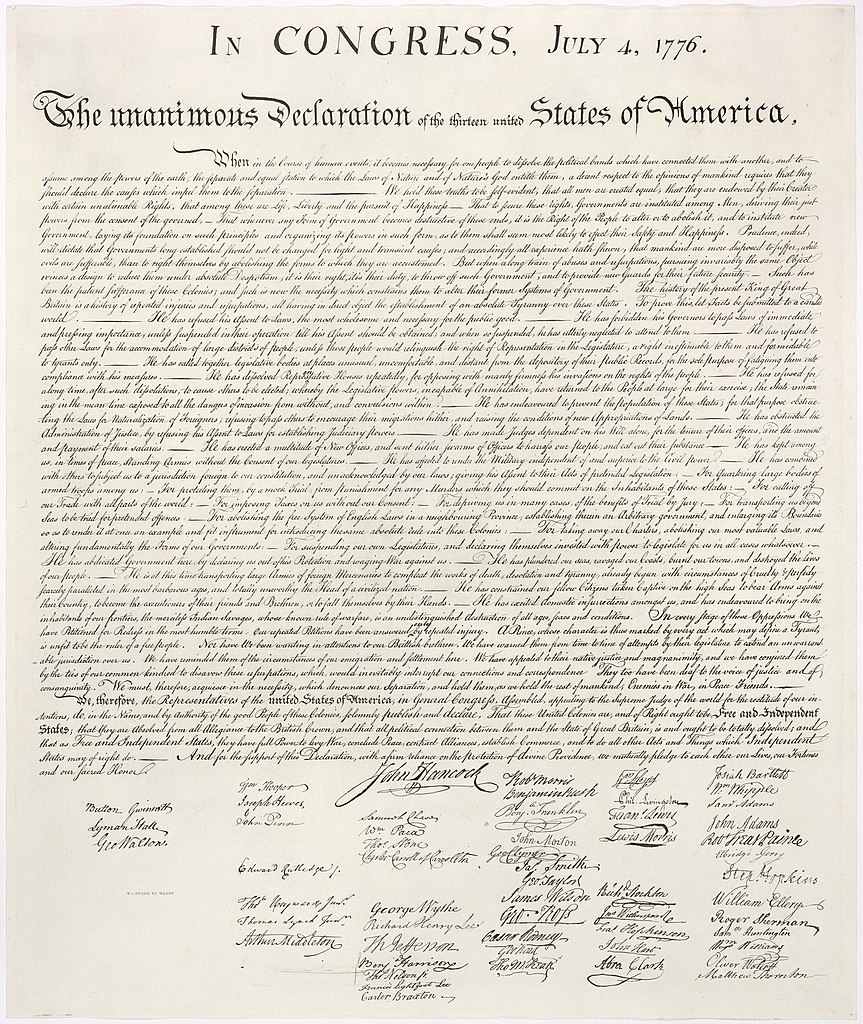

Once independence had been adopted, Congress again formed itself into a Committee of the Whole. It then spent the better part of two days editing the draft declaration submitted by its Committee of Five, rewriting or chopping off large sections of text. Finally, on July 4, Congress approved the revised Declaration and ordered it to be printed and sent to the several states and to the commanding officers of the Continental Army. By formally announcing and justifying the end of British rule, that document, as letters from Congress’s president, John Hancock, explained, laid “the Ground & Foundation” of American self-government. As a result, it had to be proclaimed not only before American troops in the hope that it would inspire them to fight more ardently for what was now the cause of both liberty and national independence but throughout the country, and “in such a Manner, that the People may be universally informed of it.”

Not until four days later did a committee of Congress— not Congress itself—get around to sending a copy of the Declaration to its emissary in Paris, Silas Deane, with orders to present it to the court of France and send copies to “the other Courts of Europe.” Unfortunately the original letter was lost, and the next failed to reach Deane until November, when news of American independence had circulated for months. To make matters worse, it arrived with only a brief note from the committee and in an envelope that lacked a seal, an unfortunately slipshod way, complained Deane, to announce the arrival of the United States among the powers of the earth to “old and powerful! states.” Despite the Declaration’s reference to the “opinions of mankind,” it was obviously meant first and foremost for a home audience.

As copies of the Declaration spread through the states and were publicly read at town meetings, religious services, court days, or wherever else people assembled, Americans marked the occasion with appropriate rituals. They lit great bonfires, “illuminated” their windows with

But what exactly were they celebrating? The news, not the vehicle that brought it; independence and the assumption of self-government, not the document that announced Congress’s decision to break with Britain. Considering how revered a position the Declaration of Independence later won in the minds and hearts of the people, Americans’ disregard for it in the first years of the new nation verges on the unbelievable. One colonial newspaper dismissed the Declaration’s extensive charges against the king as just another “recapitulation of injuries,” one, it seems, in a series, and not particularly remarkable compared with earlier “catalogues of grievances.” Citations of the Declaration were usually drawn from its final paragraph, which said that the united colonies “are and of Right ought to be Free and Independent states” and were “Absolved of all Allegiance to the British Crown” —words from the Lee resolution that Congress had inserted into the committee draft. Independence was new; the rest of the Declaration seemed all too familiar to Americans, a restatement of what they and their representatives had already said time and again.

The adoption of independence was, however, from the beginning confused with its declaration. Differences in the meaning of the word declare contributed to the confusion. Before the Declaration of Independence was issued—while, in fact, Congress was still editing Jefferson’s draft—Pennsylvania newspapers announced that on July 2 the Continental Congress had “declared the United Colonies Free and Independent States,” by which it meant simply that it had officially accepted that status. Newspapers in other colonies repeated the story. In later years the “Anniversary of the United States of America” came to be celebrated on the date Congress had approved the Declaration of Independence. That began, it seems, by accident. In 1777 no member of Congress thought of marking the anniversary of independence at all until July 3, when it was too late to honor July 2. As a result, the celebration took place on the Fourth, and that became the tradition. At least one delegate spoke of “celebrating the Anniversary of the Declaration of Independence,” but over the next few years references to the anniversary of independence and of the Declaration seem to have been virtually interchangeable.

Accounts of the events at Philadelphia on July 4, 1777, say quite a bit about the music played by a band of Hessian soldiers who had been captured at the Battle of Trenton the previous December, and the “splended illumination” of houses, but little about

In fact, one of the very few public comments on the document’s literary qualities came in a Virginia newspaper’s account of a 1777 speech by John Wilkes, an English radical and a long-time supporter of the Americans, in the House of Commons. Wilkes set out to answer a fellow member of Parliament who had attacked the Declaration of Independence as “a wretched compostion, very ill written, drawn up with a view to captivate the people.” Curiously, Wilkes seemed to agree with that description. The purpose of the document, he said, was indeed to captivate the American people, who were not much impressed by “the polished periods, the harmonious, happy expressions, with all the grace, ease, and elegance of a beautiful diction” that Englishmen valued. What they liked was “manly, nervous sense … even in the most awkward and uncouth dress of language.”

All that began to change in the 1790s, when, in the midst of bitter partisan conflict, the modern understanding and reputation of the Declaration of Independence first emerged. Until that time celebrations of the Fourth were controlled by nationalists who found a home in the Federalist party, and their earlier inattention to the Declaration hardened into a rigid hostility after 1790. The document’s anti-British character was an embarrassment to Federalists who sought economic and diplomatic rapprochement with Britain. The language of equality and rights in the Declaration was different from that of the Declaration of the Rights of Man issued by the French National Assembly in 1789, but it still seemed too “French” for the comfort of Federalists, who, after the execution of Louis XVI and the onset of the Terror, lost whatever sympathy for the French Revolution they had once felt. Moreover, they understandably found it best to say as little as possible about a fundamental American text that had been drafted by a leader of the opposing Republican party.

It was, then, the Republicans who began to celebrate the Declaration of Independence as a “deathless instrument” written by “the immortal Jefferson.” The Republicans saw themselves as the defenders of the American Republic of 1776 against subversion by pro-British “monarchists,” and they

The Federalists responded that Jefferson had not written the Declaration alone. The drafting committee—including John Adams, a Federalist—had also contributed to its creation. And Jefferson’s role as “the scribe who penned the declaration” had not been so distinguished as his followers suggested. Federalists rediscovered similarities between the Declaration and Locke’s Second Treatise of Government that Richard Henry Lee had noticed long before and used them to argue that even the “small part of that memorable instrument” that could be attributed to Jefferson “he stole from Locke’s Essays.” But, after the War of 1812, the Federalist party slipped from sight, and with it, efforts to disparage the Declaration of Independence.

When a new party system formed in the late 1820s and 1830s, both Whigs and Jacksonians claimed descent from Jefferson and his party and so accepted the old Republican position on the Declaration and Jefferson’s glorious role in its creation. By then, too, a new generation of Americans had come of age and made preservation of the nation’s revolutionary history its particular mission. Its efforts, and its reverential attitude toward the revolutionaries and their works, also helped establish the Declaration of Independence as an important icon of American identity.

The change came suddenly. As late as January 1817, John Adams said that his country had no interest in its past. “I see no disposition to celebrate or remember, or even Curiosity to enquire into the Characters, Actions, or Events of the Revolution,” he wrote the artist John Trumbull. But a little more than a month later Congress commissioned Trumbull to produce four large paintings commemorating the Revolution, which were to hang in the rotunda of the new American Capitol. For Trumbull, the most important of the series, and the one to which he first turned, was the Declaration of Independence. He based that work on a smaller painting he had done between 1786 and 1793

Soon copies of the document were being published and sold briskly, which perhaps was what inspired Secretary of State John Quincy Adams to have an exact facsimile of the Declaration, the only one ever produced, made in 1823. Congress had it distributed throughout the country. Books also started to appear: the collected biographies of those who signed the Declaration in nine volumes by Joseph M. Sanderson (1823–27) or one volume by Charles A. Goodrich (1831), full biographies of individual revolutionaries that were often written by descendants who used family papers, and collections of revolutionary documents edited by such notable figures as Hezekiah Niles, Jared Sparks, and Peter Force.

Postwar efforts to preserve the memories and records ofthe Revolution were undertaken in a mood of near panic. Many documents remained in private hands, where they were gradually separated from one another and lost. Even worse, many revolutionaries had died, taking with them precious memories that were gone forever. The presence of living remnants of the revolutionary generation seemed so important in preserving its tradition that Americans watched anxiously as their numbers declined.

These attitudes first appeared in the decade before 1826, the fiftieth anniversary of independence, but they persisted on into the Civil War. In 1864 the Reverend Elias Brewster Hillard noted that only seven of those who had fought in the Revolutionary War still survived, and he hurried to interview and photograph those “venerable and now sacred men” for the benefit of posterity. “The present is the last generation that will be connected by living link with the great period in which our national independence was achieved,” he wrote in the introduction to his book The Last Men of the Revolution. “Our own are the last eyes that will look on men who looked on Washington; our ears the last that will hear the living voices of those who heard his words. Henceforth the American Revolution will be known among men by the silent record of history alone.”

Most of the men Hillard interviewed had played modest roles in the Revolution. In the early 1820s, however, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson were still alive, and as the only surviving members of the committee that had drafted the Declaration of Independence, they attracted an extraordinary outpouring of attention. Pilgrims, invited and uninvited, flocked particularly to Monticello, hoping to catch a glimpse of

Adams, in truth, was miffed by Jefferson’s celebrity as the penman of Independence. The drafting of the Declaration of Independence, he thought, had assumed an exaggerated importance. Jefferson perhaps agreed; he, too, cautioned a correspondent against giving too much emphasis to “mere composition.” The Declaration, he said, had not and had not been meant to be an original or novel creation; his assignment had been to produce “an expression of the American mind, and to give that expression the proper tone and spirit called for by the occasion.”

Jefferson, however, played an important role in rescuing the Declaration from obscurity and making it a defining event of the revolutionary “heroic age.” It was he who first suggested that the young John Trumbull paint The Declaration of Independence. And Trumbull’s first sketch of his famous painting shares a piece of drawing paper with a sketch by Jefferson, executed in Paris sometime in 1786, of the assembly room in the Old Pennsylvania State House, now known as Independence Hall. Trumbull’s painting of the scene carefully followed Jefferson’s sketch, which unfortunately included architectural inaccuracies, as Trumbull later learned to his dismay.

Jefferson also spent hour after hour answering, in longhand, letters that he said numbered 1267 in 1820, many of which asked questions about the Declaration and its creation. Unfortunately, his responses, like the sketch he made for Trumbull, were inaccurate in many details. Even his account of the drafting process, retold in an important letter to James Madison of 1823 that has been accepted by one authority after another, conflicts with a note he sent Benjamin Franklin in June 1776. Jefferson forgot, in short, how substantial a role other members of the drafting committee had played in framing the Declaration and adjusting its text before it was submitted to Congress.

Indeed, in old age Jefferson found enormous consolation in the fact that he was, as he ordered inscribed on his tomb, “Author of the Declaration of American Independence.” More than anything else he had done, that role came to justify his life. It saved him from a despair that he suffered at the time of the Missouri crisis, when everything the Revolution had accomplished seemed to him in jeopardy, and that was later fed by problems at the University of Virginia, his own deteriorating health, and personal financial troubles so severe that he feared the loss of his beloved home, Monticello (those troubles, incidentally, virtually precluded him from freeing more than a handful of slaves at

But just which principles did he mean? Those in the Declaration’s second paragraph, which he understood exactly as they had been understood in 1776—as an assertion primarily of the right of revolution. Jefferson composed the long sentence beginning “We hold these truths to be self-evident” in a well-known eighteenth-century rhetorical style by which one phrase was piled on another and the meaning of the whole became clear only at the end. The sequence ended with an assertion of the “Right of the People to alter or to abolish” any government that failed to secure their in-alienable rights and to institute a new form of government more likely “to effect their Safety and Happiness.” That was the right Americans were exercising in July 1776, and it seemed no less relevant in the 1820s, when revolutionary movements were sweeping through Europe and Latin America. The American example would be, as Jefferson said in the last letter of his life, a “signal arousing men to burst the chains under which monkish ignorance and superstition had persuaded them to bind themselves, and to assume the blessings and security of self-government.”

Others, however, emphasized the opening phrases of the sentence that began the Declaration’s second paragraph, particularly “the memorable assertion, that ‘all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, and that to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.’” That passage, the eulogist John Sergeant said at Philadelphia in July 1826, was the “text of the revolution,” the “ruling vital principle” that had inspired the men of the 1770s, who “looked forward through succeeding generations, and saw stamped upon all their institutions, the great principles set forth in the Declaration of Independence.” In Hallowell, Maine, another eulogist, Peleg Sprague, similarly described the Declaration of Independence as an assertion “ by a whole people , of… the native equality of the human race , as the true foundation of all political, of all human institutions.”

And so an interpretation of the Declaration that had emerged in the 1790s became ever more widely repeated. The equality that Sergeant and Sprague emphasized was not, however, asserted for the first time in the

Jefferson was not alone in adapting the Mason text for his purposes. The Virginia convention revised the Mason draft before enacting Virginia’s Declaration of Rights, which said that all men were “by nature” equally free and independent. Several other states—including Pennsylvania (1776), Vermont (1777), Massachusetts (1780), and New Hampshire (1784)—remained closer to Mason’s wording, including in their state bill of rights the assertions that men were “born free and equal” or “born equally free and independent.” Unlike the Declaration of Independence, moreover, the state bills or “declarations” of rights became (after an initial period of confusion) legally binding. Americans’ first efforts to work out the meaning of the equality written into their founding documents therefore occurred on the state level.

In Massachusetts, for example, several slaves won their freedom in the 1780s by arguing before the state’s Supreme Judicial Court that the provision in the state’s bill of rights that all men were born free and equal made slavery unlawful. Later, in the famous case of Commonwealth v. Aves (1836), Justice Lemuel Shaw ruled that those words were sufficient to end slavery in Massachusetts, indeed that it would be difficult to find others “more precisely adapted to the abolition of negro slavery.” White Americans also found the equality provisions in their state bills of rights useful. In the Virginia constitutional convention of 1829–30, for example, a delegate from the trans-Appalachian West, John R. Cooke, cited that “sacred instrument” the Virginia Declaration of Rights against the state’s system of representing all counties equally in the legislature regardless of their populations and its imposition of a property qualification for the vote, both of which gave disproportional power to men in the eastern part of the state. The framers of Virginia’s 1776 constitution allowed those practices to persist despite their violation of the equality affirmed in the Declaration of Rights, Cooke said, because there were limits on how much they dared

But why, if the states had legally binding statements of men’s equality, should anyone turn to the Declaration of Independence? Because not all states had bills of rights, and not all the bills of rights that did exist included statements on equality. Moreover, neither the federal Constitution nor the federal Bill of Rights asserted men’s natural equality or their possession of inalienable rights or the right of the people to reject or change their government. As a result, contenders in national politics who found those old revolutionary principles useful had to cite the Declaration of Independence. It was all they had.

The sacred stature given the Declaration after 1815 made it extremely useful for causes attempting to seize the moral high ground in public debate. Beginning about 1820, workers, farmers, women’s rights advocates, and other groups persistently used the Declaration of Independence to justify their quest for equality and their opposition to the “tyranny” of factory owners or railroads or great corporations or the male power structure. It remained, however, especially easy for the opponents of slavery to cite the Declaration on behalf of their cause. Eighteenth-century statements of equality referred to men in a state of nature, before governments were created, and asserted that no persons acquired legitimate authority over others without their consent. If so, a system of slavery in which men were born the subjects and indeed the property of others was profoundly wrong. In short, the same principle that denied kings a right to rule by inheritance alone undercut the right of masters to own slaves whose status was determined by birth, not consent. The kinship of the Declaration of Independence with the cause of antislavery was understood from the beginning—which explains why gradual emancipation acts, such as those in New York and New Jersey, took effect on July 4 in 1799 and 1804 and why Nat Turner’s rebellion was originally planned for July 4, 1831.

Even in the eighteenth century, however, assertions of men’s equal birth provoked dissent. As slavery became an increasingly divisive issue, denials that men were naturally equal multiplied. Men were not created equal in Virginia, John Tyler insisted during the Missouri debates of 1820: “No, sir, the principle, although lovely and beautiful, cannot obliterate those distinctions in society which society itself engenders and gives birth to.” Six years later the acerbic, self-styled Virginia aristocrat John Randolph called the notion of man’s equal creation “a falsehood, and a most pernicious falsehood, even though I find it in the Declaration of Independence.” Man was born in a state of “perfect helplessness and ignorance” and so was from the start dependent

Five years later, in senate debates over the Kansas-Nebraska Act, Indiana’s John Pettit pronounced his widely quoted statement that the supposed “self-evident truth” of man’s equal creation was in fact “a self-evident lie.” Ohio’s senator Benjamin Franklin Wade, an outspoken opponent of slavery known for his vituperative style and intense patriotism, rose to reply. Perhaps Wade’s first and middle names gave him a special bond with the Declaration and its creators. The “great declaration cost our forefathers too dear,” he said, to be so “lightly thrown away by their children.” Without its inspiring principles the Americans could not have won their independence; for the revolutionary generation the “great truths” in that “immortal instrument,” the Declaration of Independence, were “worth the sacrifice of all else on earth, even life itself.” How, then, were men equal? Not, surely, in physical power or intellect. The “good old Declaration” said “that all men are equal, and have inalienable rights; that is, [they are] equal in point of right; that no man has a right to trample on another.” Where those rights were wrested from men through force or fraud, justice demanded that they be “restored without delay.”

Abraham Lincoln, a little-known forty-four-year-old lawyer in Springfield, Illinois, who had served one term in Congress before being turned our of office, read these debates, was aroused as by nothing before, and began to pick up the dropped threads of his political career. Like Wade, Lincoln idealized the men of the American Revolution, who were for him “a forest of giant oaks,” “a fortress of strength,” “iron men.” He also shared the deep concern of his contemporaries as the “silent artillery of time” removed them and the “ living history ” they embodied from this world.

Before the 1850s, however, Lincoln seems to have had relatively little interest in the Declaration of Independence. Then, suddenly, that document and its assertion that all men were created equal became his “ancient faith,” the “father of all moral principles,” an “axiom” of free society. He was provoked by the attacks of men such as Pettit and Calhoun. And he made the arguments of

Lincoln’s position emerged fully and powerfully during his debates with Illinois’s senator Stephen Douglas, a Democrat who had proposed the Kansas-Nebraska Act and whose seat Lincoln sought in 1858. They were an odd couple, Douglas and Lincoln, as different physically—at full height Douglas came only to Lincoln’s shoulders—as they were in style. Douglas wore well-tailored clothes; Lincoln’s barely covered his limbs. Douglas was in general the more polished speaker; Lincoln sometimes rambled on, losing his point and his audience, although he could also, especially with a prepared text, be a powerful orator. The greatest difference between them was, however, in the positions they took on the future of slavery and the meaning of the Declaration of Independence.

Douglas defended the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which allowed the people of those states to permit slavery within their borders, as consistent with the revolutionary heritage. After all, in instructing their delegates to vote for independence, one state after another had explicitly retained the exclusive right of defining its domestic institutions. Moreover, the Declaration of Independence carried no implications for slavery, since its statement on equality referred to white men only. In fact, Douglas said, it simply meant that American colonists of European descent had equal rights with the King’s subjects in Great Britain. The signers were not thinking of “the negro or … savage Indians, or the Feejee, or the Malay, or any other inferior or degraded race.” Otherwise they would have been honor bound to free their own slaves, which not even Thomas Jefferson did. The Declaration had only one purpose: to explain and justify American independence.

To Lincoln, Douglas’s argument left only a “mangled ruin” of the Declaration of Independence, whose “plain, unmistakable language” said “ all men” were created equal. In affirming that government derived its “just powers from the consent of the governed,” the Declaration also said that no man could rightly govern others without their consent. If, then, “the negro is a man,” was it not a “total destruction of self-government, to say that he too shall not govern himself ?” To govern a man without his consent was “despotism.” Moreover, to confine the document's significance to the British peoples of 1776 denied its meaning, Lincoln charged, not only for Douglas’s “inferior races” but for the French, Irish, German, Scandinavian, and other immigrants who had come to America after the Revolution. For them the promise of equality linked new Americans with the founding generation; it was an “electric cord” that bound them into the nation “as though they were blood of the blood, and flesh of the flesh of the men who wrote that Declaration,” and so made

Like Wade, Lincoln denied that the signers meant that men were equal in “ all respects ,” including “color, size, intellect, moral developments, or social capacity.” He, too, made sense of the Declaration’s assertion of man’s equal creation by eliding it with the next, separate statement on rights. The signers, he insisted, said men were equal in having “‘certain inalienable rights….’ This they said, and this they meant.” Like John Cooke in Virginia three decades before, Lincoln thought the Founders allowed the persistence of practices at odds with their principles for reasons of necessity: to establish the Constitution demanded that slavery continue in those original states that chose to keep it. “We could not secure the good we did if we grasped for more,” but that did not “destroy the principle that is the charter of our liberties.” Nor did it mean that slavery had to be allowed in states not yet organized in 1776, such as Kansas and Nebraska.

Again like Cooke, Lincoln claimed that the authors of the Declaration understood its second paragraph as setting a standard for free men whose principles should be realized “as fast as circumstances … permit.” They wanted that standard to be “familiar to all, and revered by all; constantly looked to, and constantly labored for, and even though never perfectly attained, constantly approximated and thereby constantly spreading and deepening its influence, and augmenting the happiness and value of life to all people of all colors everywhere.” And if, as Calhoun said, American independence could have been declared without any assertion of human equality and inalienable rights, that made its inclusion all the more wonderful. “All honor to Jefferson,” Lincoln said in a letter of 1859, “to the man who … had the coolness, forecast, and capacity to introduce into a merely revolutionary document, an abstract truth, applicable to all men and all times, and to embalm it there,” where it would remain “a rebuke and a stumbling-block to the very harbingers of re-appearing tyranny and oppression.”

Jefferson and the members of the second continental Congress did not understand what they were doing in quite that way on July 4, 1776. For them, it was enough for the Declaration to be “merely revolutionary.” But, if Douglas’s history was more accurate, Lincoln’s reading of the Declaration was better suited

Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address stated briefly and eloquently convictions he had developed over the previous decade, convictions that on point after point echoed earlier Americans: Republicans of the 1790s, the eulogists Peleg Sprague and John Sergeant in 1826, John Cooke in the Virginia convention a few years later, Benjamin Wade in 1853. Some of those men he knew; others were unfamiliar to him, but they had also struggled to understand the practical implications of their revolutionary heritage and followed the same logic to the same conclusions. The Declaration of Independence that Lincoln left was not Jefferson’s Declaration, although Jefferson and other revolutionaries shared the values which Lincoln and others stressed: equality, human rights, government by consent. Nor was Lincoln’s Declaration of Independence solely his creation. It remained an “expression of the American mind,” not, of course, what all Americans thought but what many had come to accept. And its implications continued to evolve after Lincoln’s death. In 1858, he had written a correspondent that the language of the Declaration of Independence was at odds with slavery but did not require political and social equality for free black Americans. Few disagreed then. How many would agree today?

The Declaration of Independence is in fact a curious document. After the Civil War, members of Lincoln’s party tried to write its principles into the Constitution by enacting the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments, which is why issues of racial or age or gender equality are now so often fought out in the courts. But the Declaration itself is not and has never been legally binding. Its power comes from its capacity to inspire and move the hearts of living Americans, and its meaning lies in what they choose to make of it. It has been at once a cause of controversy,