Authors:

Historic Era: Era 10: Contemporary United States (1968 to the present)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

June 2021 | Volume 66, Issue 4

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 10: Contemporary United States (1968 to the present)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

June 2021 | Volume 66, Issue 4

Editor’s Note: James Reston, Jr. is a Vietnam-era veteran and author of seventeen books including A Rift in the Earth: Art, Memory, and the Fight for a Vietnam War Memorial about the founding of the Wall. His latest book is a 9/11 novel, The Nineteenth Hijacker, published in February.

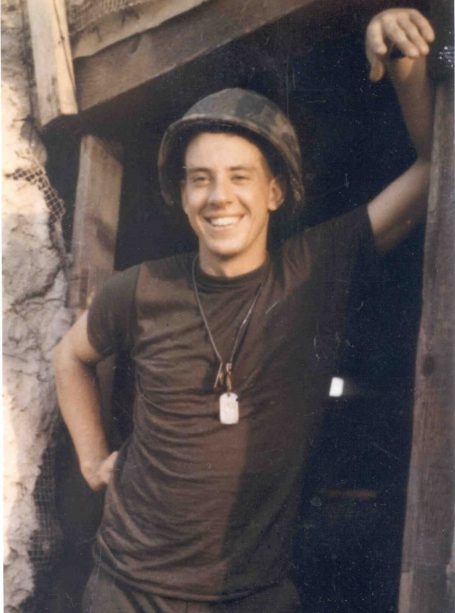

Torment was acute for many veterans in the years after the Vietnam War ended. More than 2.1 million men and women deployed over the course of the conflict, and returning soldiers were often scorned and humiliated as purveyors of death and torture, and dupes of a discredited policy. College friends looked on veterans’ service with mystification and disapproval, while they moved forward with careers or cared for trick knees.

How should a country heal after such a divisive war? What could be done to bring the rage and recrimination to an end? How long would the reconciliation take—if indeed the healing could ever happen?

Please sign our petition to ask President Biden to award the Presidential Medal to Jan Scruggs for his efforts to create the Vietnam Wall and heal our nation’s division.

From 1978 to 1984, those profound questions were encapsulated in a brawl over how to commemorate the war, the first the United States had ever lost. It was an extraordinary struggle between groups with different attitudes toward what some called the 20th Century’s “lost cause,” and what constitutes honor and courage in times of national crisis. It was also a fight between people with different notions about public art.

At the time, the competition for an appropriate design to commemorate the sacrifice in Vietnam was the largest contest of its kind in the history of art with 1421 entries—a remarkable explosion of creativity. The surprising winner was a twenty-one-year-old Yale undergraduate named Maya Lin, whose concept of a simple, chevron-shaped black granite wall became instantly controversial. A cabal of well-connected, forceful veterans led the charge against it, denigrating the design as shameful and nihilistic, an insult to veterans and a paean to anti-war protesters. They did everything they could to scuttle the winning design and replace it with something more “heroic”… and they almost succeeded.

Long after the Vietnam conflict, the struggle remains intensely relevant for wars that America may fight in the future. The memorial on the National Mall is no longer just about veterans and their loss and sacrifice, no longer just about Vietnam, but about all wars and all service to country as well as moral opposition to governmental authority.

No one could have predicted that this simple space of contemplation has become one of the most popular sites in the nation’s capital, with over three million visitors a year. This simple V