Authors:

Historic Era: Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Spring 2021 | Volume 66, Issue 3

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Spring 2021 | Volume 66, Issue 3

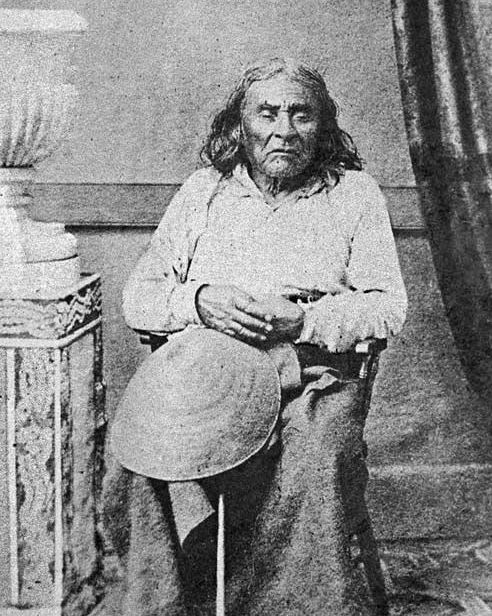

It is possible to walk down a rough, rain-lashed street in Seattle and stand near where Chief Seattle, the city’s namesake, delivered a speech considered to be one of the greatest ever given by any Native American. But you will be alone in your effort, and won’t find a statue, a sign or even an ‘X’ to mark the spot.

Seattle is the largest city in the world named after a Native American, but most city residents would be hard-pressed to describe him. Ironically, much of this is due to the debate surrounding the famed speech that he gave in 1854, at a time when his people’s numbers were dwindling, and to an audience that included the Washington Territory’s first governor. Not printed until 1887, the speech has taken many different forms over the ensuing century and a half, evolving from a paean of peace and territorial sovereignty to its more recent rendering as an environmentalist anthem. After all these years, the question remains: Which version of Seattle’s speech is the true one?

When Seattle died on June 7, 1866, he had been exiled from his town for over a year, driven out in an effort to spiff up the place’s rough image. At his death, neither of the territorial newspapers mentioned his passing, that of a Native leader who, on February 28, 1856, had been quoted on the front page of the New York Herald’s morning edition.

The town’s name kept his memory alive, but the question “Why would you name your town after an Indian?” was more an accusation. In 1875, a popular travel writer, Charles Nordhoff (grandfather of the H. M. S. Bounty trilogy’s co-author) wrote: “When… you enter Washington Territory, your ears begin to be assailed by the most barbarous names imaginable.” After citing “Skookum-Chuck…Nenelops …Toutle.” He added, “Seattle is similarly barbarous.”

The man himself did not escape similar derogatory criticisms. In 1890, western historian Charles Bancroft described him as a “naked savage who conversed only in signs and grunts.” The same disdain has prevailed. In his 1978 biography, Doc Maynard: The Man Who Invented Seattle, Bill Speidel writes that when speaking, Seattle “sounded like a demonstration by the winner of an Iowa hog-calling contest.”

In his speech, Seattle welcomed Washington Territory’s diminutive first governor, Isaac Stevens – also known as “Little Rough and Ready,” or, depending on your politics, “Little Bandy-legged Tyrant”– when he arrived in the newly named town on January 10,