Authors:

Historic Era: Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

December 1996 | Volume 47, Issue 8

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

December 1996 | Volume 47, Issue 8

Readers, our fearful trip through another presidential election is done. Whatever we may each feel about the results, it is time to relax, remind ourselves that the world will go on revolving, and prepare to celebrate the end of another of its rotations. In other words, perhaps it is appropriate in this holiday month to look at changing American fashions in seeing in the New Year.

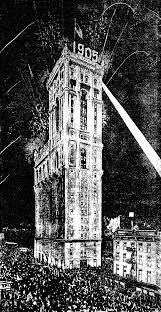

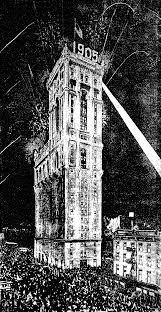

Many among us will pass New Year’s Eve in what we think of as a traditional manner, partying with friends, singing “Auld Lang Syne,” and possibly watching the televised seventy-seven-foot descent of a lighted six-foot-high sphere down a pole atop One Times Square, New York City, timed to take up precisely the last 60 seconds of the outgoing year. And on the next afternoon, following a long, late breakfast, millions of football addicts, in company or alone, hung-over or healthy, will slump before television sets watching a seemingly endless succession of intercollegiate games. Of course, “traditions” in this country sometimes have surprisingly short lives.

Robert Burns’s “Auld Lang Syne” was written in 1788. And the dropping of the ball in Times Square dates respectably back to 1907, when a signmaker and metalworker named Jacob Starr—fittingly for America a Russian immigrant—built the first such sphere. As for those bowl games, the oldest of them, the Rose Bowl, has been part of Pasadena’s Tournament of Roses continuously since 1916. The Rose Parade that nowadays precedes the kickoff was first held in 1886, when it was sponsored by a private hunt club. Soon it became a civic festival that yoked the buoyancy and high visibility of celebrating a new year to the purposes of California public relations. That, too, seems especially American.

It goes without saying that the roots of the holiday are ancient and universal. Christmas and New Year’s both fall close to the time of the winter solstice, the shortest day of the year and thus the occasion of a number of pre-Christian festivals that mingle awe and celebration. The Romans, whose calendar we still use, marked the season with the feast called Saturnalia, a time of gifts, merrymaking, and masquerade. That’s one obvious origin of our partying. There are also “new years” tied to other calendars and traditions. Rosh Hashanah, “the beginning of the year,” which Jews observe in early autumn, starts a ten-day period of penitence. Chinese tradition sets the holiday in early February, and in cities with significant populations of Chinese descent there are boisterous parades with dancing “dragons” and firecrackers to frighten away any evil presences hovering over the coming year. There is a positive folkloric feast in tracking year-end rituals around the globe. Many of them found their way to American shores in