Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Spring 2021 | Volume 66, Issue 3

Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Spring 2021 | Volume 66, Issue 3

Editor's Note: Bruce Watson is a writer, historian, and contributing editor at American Heritage. You can read more of his work on his blog, The Attic.

One morning last fall, I found myself driving along the Miller’s River as it winds through Western Massachusetts. The sun was a pale disc burning through wisps of gauze. Mist rose over the rolling river, soaring above autumnal reds and yellows. Despite my destination – Boston – it suddenly seemed as if I were westbound, crossing the Appalachians, headed for a better country, a country I used to know. Moved by the scenery, I flipped my iPod to my favorite American song. You know it. Above the din of our lives, you can hear it.

Forget, for a moment, all the would-be anthems written before or since. This land may be my land, but it’s come to feel like someone else's. Amber waves of grain are out there somewhere, but lately, dirges have doused my soul. I have not felt at home on the range in years. And as for the dawn’s early light, who among us has seen it lately? But this song…

On that morning, for that moment, the song spanned centuries. And as if bound across the wide Missouri, I drove deeper into a country I knew again. The road took me along the river, into shadowed gorges, above quilts of birch and maple. The chorus swelled and the song ended, only to be played again with the flip of a finger.

I had always loved the song, always teared up. What I love most about “Shenandoah” is that no one knows who wrote it. We don’t know where in America it was written, nor are we certain who or what this Shenandoah is.

This much I knew: Shenandoah is a gorgeous valley in Virginia, but the “wide Missouri” does not flow there. Was the singer bidding farewell, heading west? Perhaps, but early on, another interpretation arises.

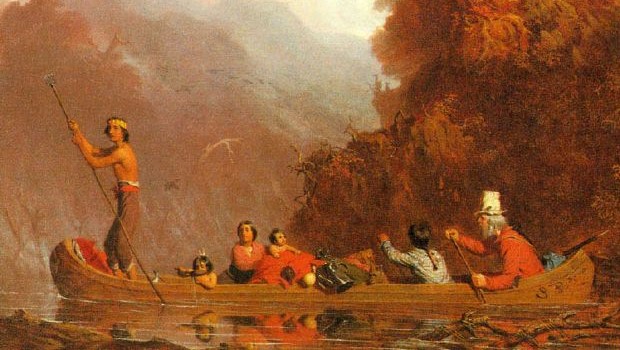

So Shenandoah was also a Native-American chief. But the song made scant mention of natives. Written by that greatest of all songwriters, Traditional, the song's aching beauty proved that tradition knows us – knows our longing, our dreams, and how often dreams shift into a minor key.

The road bound me away from the Miller’s River and on toward Boston. On a busy fall morning, fellow Americans zipped past. Some had their own internal music, but none heard a song so lyrical, so lovely, so American as “Shenandoah.”

I