Authors:

Historic Era: Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2021, Summer 2025 | Volume 66, Issue 1

Authors: Peter Cozzens

Historic Era: Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2021, Summer 2025 | Volume 66, Issue 1

Editor’s Note: One of the most respected historians of the Civil War and Indian conflicts, Peter Cozzens has written 17 books and is now at work on the third volume of a trilogy about the Indian wars in the American West, the Old Northwest (America’s Heartland), and the Old Southwest (the Deep South). Portions of this essay appear in the second volume, Tecumseh and the Prophet: The Shawnee Brothers Who Defied a Nation, published last month by Knopf. Mr. Cozzens’ 2016 book, The Earth is Weeping: The Epic Story of the Indian Wars of the American West, won the Gilder Lehrman Prize for Military History and is the first volume in the trilogy, which will conclude with A Brutal Reckoning: Andrew Jackson, the Creek Indians, and the Epic War for the American South, projected for publication in 2023.

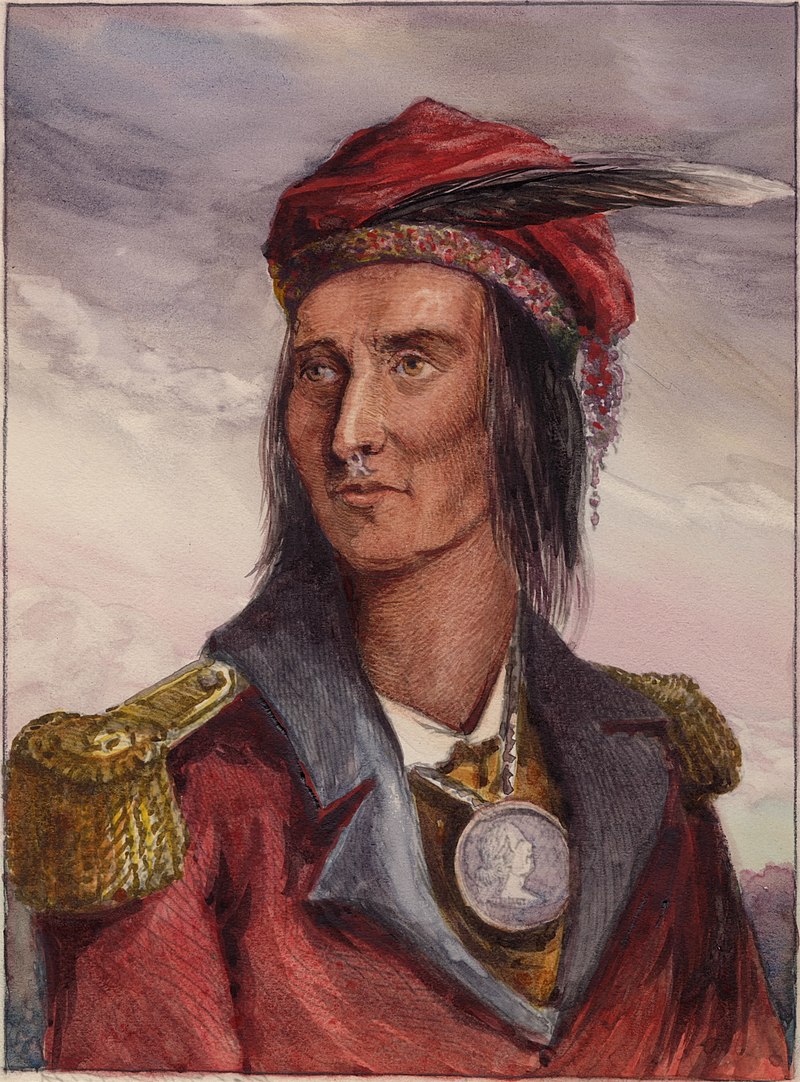

Gov. William Henry Harrison of the Indiana Territory was amazed. In a decade on the frontier implementing a fiercely acquisitive government land policy, he had met with scores of Indian chiefs, some defiant, others malleable. Never, however, had he encountered a native leader like the Shawnee chief Tecumseh, the man he considered his principal opponent in the fight for the Northwest, as present-day Ohio, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, and Wisconsin were then known.

After a contentious council with Tecumseh in July 1811, Harrison penned a remarkable tribute to him, arguably the most effusive praise a government official ever offered an American Indian leader. Tecumseh had parried Harrison’s every verbal thrust, eloquently defending his refusal to relinquish what Harrison considered “one of the fairest portions of the globe, [then] the haunt of a few wretched savages.”

There was nothing remotely wretched about Tecumseh, however. As Harrison told the secretary of war, “The implicit obedience and respect which the followers of Tecumseh pay to him is really astonishing, and more than any other circumstance bespeaks him one of those uncommon geniuses which spring up occasionally to produce revolutions and overturn the established order of things. If it were not for the vicinity of the United States, he would, perhaps, be the founder of an empire that would rival in glory that of Mexico or Peru.”

Harrison marveled at the vigor with which the Shawnee chief pursued his dream of an Indian union. “No difficulties deter him. His activity and industry supply the want of letters. For four years he has been in constant motion. You see him today on the Wabash and in a short time you hear of him on the shores of Lake Erie or Michigan, or on the banks of the Mississippi, and wherever he goes he makes an impression favorable to his purposes.”

Harrison’s testimonial encapsulates the talents of this passionate

Fables flower where facts are few or forgotten. Myths endure when people want to believe them. So it was with the Shawnee brothers. Tecumseh would come to personify for Americans all that was great and noble in the Indian character as non-Indians (whites, in the parlance of the time) perceived greatness and nobility. The reasons for this are obvious. Tecumseh advocated a political and military alliance to oppose U.S. encroachment on Indian land. This was something that whites could readily comprehend. Tecumseh, who was first and foremost a political leader, acted as they would have acted under similar circumstances.

Tenskwatawa, on the other hand, offered a divinely inspired solution to Indian land dispossession and cultural dissolution, drawing on native tradition that was beyond white understanding. Tenskwatawa’s person also repulsed whites. He was an unappealing, disfigured ex-alcoholic who as a boy had accidentally shot his right eye out with an arrow; a “man devoid of talent or merit, a brawling mischievous Indian demagogue,” according to an Indian agent who knew the Shawnee brothers intimately. The same official admired Tecumseh as the exemplar of Shawnee manhood — a skilled hunter and cunning war leader, charitable, and an orator of rare eloquence. In a similar manner, history, biography, and folklore all came to deify Tecumseh and demonize his brother as a delusional charlatan.

This unfortunate process of elevating Tecumseh at Tenskwatawa’s expense failed to give Tenskwatawa adequate credit for his role in creating and sustaining the Indian confederacy of the Shawnee brothers. It also neglected the nativist religious fervor that contributed to the emergence of Tenskwatawa and that he shaped into a coherent and enthralling doctrine. In fact, Tecumseh truly believed his brother to be a divinely inspired prophet capable of communing with the Master of Life, or Great Spirit, and also embraced his creed.

The Shawnee brothers’ grand intertribal alliance began with Tenskwatawa’s visions of eternity in 1805 and his resulting doctrine of religious and moral revitalization of Native-American society, which was rapidly declining in the Old Northwest. He called on Indians to unite

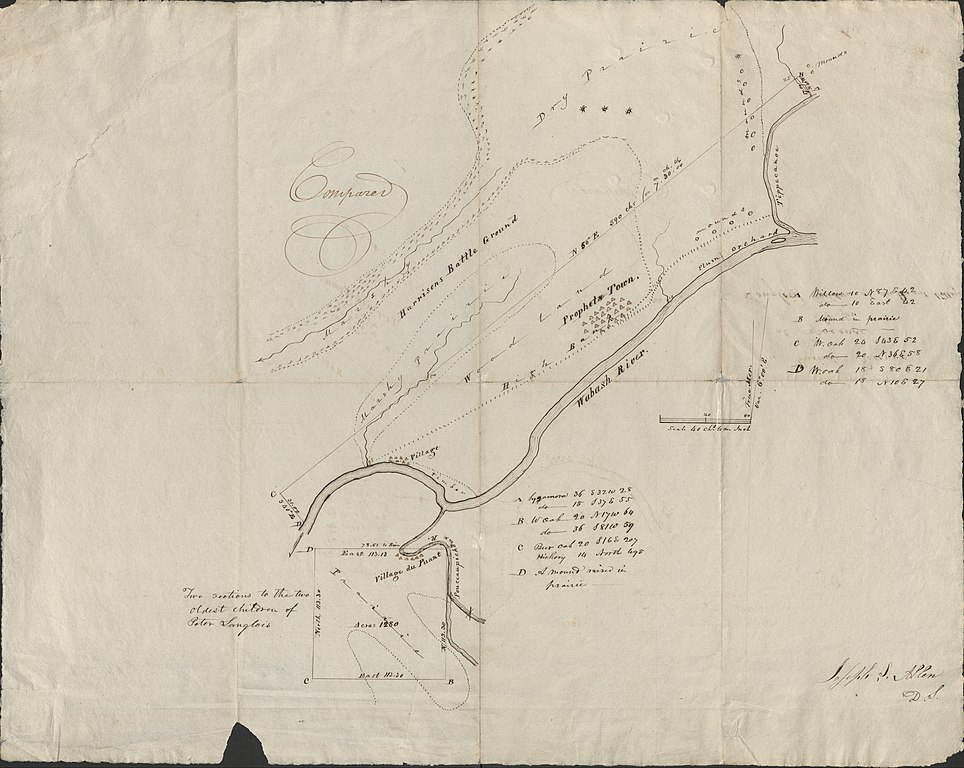

Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa had been willing to abide by a series of dubious treaties that Governor William Henry Harrison of the Indiana Territory had negotiated between 1803-1805, compacts that significantly reduced Indian lands in the Old Northwest. They warned Harrison, however, that they would oppose any future accords. Nevertheless, in 1809 Harrison concluded the shady Treaty of Fort Wayne, which deprived the Indians of millions of more acres and brought the white frontier to within sixty miles of their home village of Prophetstown, the spiritual and political center of their movement located at the junction of the Wabash and Tippecanoe rivers in what is today western Indiana. The die was cast.

Believing a defensive war against future encroachments inevitable, Tecumseh traveled south in the summer of 1811 to enlist the powerful Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Creek peoples in the alliance. Before departing, he enjoined Tenskwatawa to avoid a conflict with Harrison. As the autumn deepened, hundreds of warriors left Prophetstown for their distant villages to begin the winter hunt. Only the most militant followers from afar — Potawatomis, Kickapoos, Winnebagos, and Wyandots — remained, together with fewer than 100 Shawnee warriors, to meet any hostilities that the Long Knives, as the Indians called the American military, might provoke.

Tenskwatawa stood at a crossroads. Before Tecumseh left, the Shawnee brothers had agreed not to provoke Harrison. But Tenskwatawa soon had second thoughts. Tecumseh’s increasingly pragmatic brand of pan-Indianism was eclipsing Tenskwatawa’s leadership of the movement he had begun. And now Tecumseh was proposing a primarily political alliance with the southern tribes that would marginalize Tenskwatawa’s medicine.

Although he endorsed Tecumseh’s mission, and Tecumseh did fervently preach his younger brother’s doctrine to the southern tribes, Tenskwatawa could not find it in himself to remain idle while Tecumseh sought support in the South. And so he encouraged actions that were bound to alarm Governor Harrison, who was itching for an excuse to make war on him. In mid-September Tenskwatawa sent runners to the Kickapoos, Potawatomis, and Miamis, enjoining their warriors to return to Prophetstown. Other envoys from Prophetstown met with British agents at Amherstburg to arrange additional supplies of arms, ammunition, clothing, and blankets.

Tenskwatawa’s actions were partly defensive — the Long Knives had done their share of saber-rattling — but were ultimately counter- productive. In the porous communities of Indians, métis, and white traders, there was no concealing his machinations from Harrison and little hope that they would be conveyed to the governor honestly. Harrison’s principal informants, a French interpreter and a Delaware

It was not only whites of questionable intent and self-serving Indian spies who cast Tenskwatawa’s actions as belligerent. Seeing an opportunity to rid himself of the Shawnee brothers, Chief Black Hoof blamed Tenskwatawa for the Potawatomi chief Main Poc’s depredations in Illinois, casting him as the agent of Indian evils — past, present, and future. “Since [Tenskwatawa] situated himself on the Wabash, it has been [his] usual practice to gather the Indians about him for bad purposes, and I believe he will continue to do so,” Black Hoof told American officials in late August. “It is him that has been the principal cause of all the mischief that has been done.”

While less absolute in their condemnation of the Prophet, Little Turtle and the other Miami chiefs promised to remain neutral in any conflict between Tenskwatawa and Harrison. The Wyandots also pledged neutrality and offered to provide the Americans with “early information if we know of any mischief coming your way.”

Both the easily frightened governor Ninian Edwards of Illinois and the recently installed governor Benjamin Howard of the Louisiana Territory advocated military action against the Shawnee Prophet before Tecumseh returned from the South, presumably with reinforcements to initiate a war himself. “Whether the Prophet intends to make war or not, partial war must continue to be the consequence,” reasoned Edwards. “The hostility which he excites against the United States is the cement of union among his confederates, and such is the nature of Indians that they cannot be collected and kept together under such circumstances without having their minds prepared for war; and in that situation, it is almost impossible to restrain them from premature acts of hostility. Were this the only danger,” he cautioned the War Department, “it would be sufficient to justify the dispersion of the Prophet’s party.”

Harrison heartily concurred in the need to dismantle Prophetstown or, at a minimum, to prevent more warriors from congregating there. Tecumseh’s uncharacteristic diffidence after the altercation on the first day of their August council deepened Harrison’s conviction that recalcitrant Indians respected only brute force or the threat of its use. He peppered the secretary of war with requests for permission to march against Prophetstown. “Heedless of futurity, it is only by placing the danger before his eyes that a savage is to be controlled,” averred Harrison. “Even the gallant Tecumseh is not insensible to an argument of this kind.” The Shawnee chief had been as complaisant as a courtier on his last visit, a “wonderful metamorphosis in manner entirely produced by the gleaming and clanging of arms.”

There were discordant notes in

The tranquility at Prophetstown proved to Badollet that Tenskwatawa contemplated only a “defensive war to protect his infant settlement.” So too, at least to Badollet, did the mid-September visit to Vincennes of a delegation from Tenskwatawa proclaiming that “his heart was warm” toward the United States. The governor, however, had heard such protestations before. Seizing on a recent string of horse thefts by parties unknown as evidence of Tenskwatawa’s hostility, on September 26, Harrison started up the east bank of the Wabash River with 1,020 officers and men to disperse the warriors concentrated at Prophetstown before Tecumseh was able to bring the southern tribes into the confederacy. Instructions from Washington, D.C., were minimal: Secretary of War Eustis asked only that Harrison try to preserve the peace if possible.

Harrison led a colorful procession northward. The 404 regulars of the Fourth Infantry wore high black-visored caps, blue coatees, white pantaloons, and black gaiters and shoes. With their wide-brimmed black hats, fringed hunting shirts, linen or buckskin Kentucky jeans, and moccasins, the 616 militiamen were indistinguishable from frontier settlers. Harrison himself inclined toward western informality. An officer’s wife who saw him leave said the lankly, dark-eyed, sallow- complexioned governor had on a hunting shirt “made of calico and trimmed with fringe, the fashion of it [resembling] a woman’s short gown tied in a hard knot. On his head he wore a round beaver hat ornamented with a large ostrich feather.”

At Prophetstown, the colors Tenskwatawa wore were consternation and confusion. He had on hand approximately five hundred warriors. Indian agent John Johnston placed the number at 350, Harrison at between 450 and 600, and a resident French trader at 700. Most were militant Kickapoos, Potawatomis, and Winnebagos. There were no Miamis, only a scattering of Delawares and Ottawas, perhaps a dozen Creeks, Chief Roundhead’s small contingent of Wyandots, and fewer than fifty Shawnee warriors. Although outnumbered two to one, the Indians were well armed with British muskets. Having learned from Wayne the devastating impact of a bayonet charge at Fallen Timbers, many also carried spears to deter the Long Knives from fighting at close quarters.

Tenskwatawa had expected an enthusiastic response to his summons to the Illinois tribes, but just 125 Potawatomis answered the call. Although his gunshot wound had healed,

Tenskwatawa was furious. He made clear his anger in the speech and the black wampum belt he entrusted to loyal Potawatomi couriers to carry to their absent western allies. “Brothers,” the speech ran, “you promised me last year that you would be ready in the spring. The spring came but no person was ready. The fall has come, and I look towards the sun setting, and I cannot discern anything. You have not been true!” No longer banking on reinforcements, Tenskwatawa prudently erected a strong line of log breastworks around Prophetstown.

While Tecumseh argued his case to the Creek Indians at Tuckabatchee six hundred miles to the south, Harrison marched up the east bank of the Wabash. On October 2 he paused at the edge of vast grasslands seventy miles southwest of Prophetstown. There he erected an elaborate fortification, which his officers insisted he name Fort Harrison, and dispatched Delaware emissaries to Tenskwatawa with harsh terms: surrender warriors who had attacked American settlements (none from Prophetstown had), return stolen horses (his people had taken none), and appear immediately at a council on ground of the governor’s choosing. An uneasy interregnum obtained.

Dark clouds rolled over the prairie. Heavy rains alternated with light snowfalls, churning the ground around Fort Harrison into a pasty ooze. Food ran short. The Delawares did not return. While awaiting resupply and a reply from the Prophet, Harrison received a letter from Secretary Eustis granting him wide latitude to act as circumstances dictated so long as he com- mitted no acts that might threaten British interests. As for the Shawnee Prophet, Eustis suggested Harrison order him to dismantle Prophets- town. Should Tenskwatawa decline, Harrison was free to attack him.

With the prospect of war with Great Britain ever present, the Madison administration might have calculated it would be better to eradicate the presumably belligerent Indians before a conflict did break out.

If Harrison found himself unfettered, Tenskwatawa, by contrast, felt increasingly constrained. His own turbulent followers, as well as his previous success in beguiling the governor, choked off the Shawnee Prophet’s options as effectively as did the approaching Long Knives. Small war parties slipped out of Prophetstown, intent on winning laurels without regard for the larger consequences. Lurking Indians nightly prowled Harrison’s encampment, keeping the sentries on edge. Finally, one young warrior went too far. Creeping through the soggy brush near Harrison’s camp on the cold and cloudy night of October 10, he shot an unsuspecting sentry through the thighs and then scampered off. Another guard aimed at the musket flash, but his weapon misfired twice.

Pandemonium ensued. Nervous sentries fired on mounted

The lone Indian warrior had not only thrown a scare into Harrison’s army, but he also had doomed Prophetstown to retribution. Harrison assumed Tenskwatawa had ordered the harassment that culminated in the sentry’s wounding. His attempt at righteous indignation boomed as a hyperbolic expression of delight. “The powers given me in your last letter and circumstances which have occurred here at the very moment on which it was received call for measures of a more energetic kind,” he told Secretary Eustis, adding, “I had always supposed that the Prophet was a rash and presumptuous man, but he has exceeded expectations. He has not contented himself with throwing the gauntlet but has absolutely commenced the war.”

It is preposterous to think that Tenskwatawa would have jeopardized Prophetstown and his six years of labor gaining converts simply to score a few casualties in Harrison’s camp. But he was unable to control the wild young warriors from the western tribes. They spoiled for a fight and, as the Potawatomi chief Shabbona later confessed, sorely underestimated the Long Knives.

“If they cross the Wabash, we will take their scalps and drive them into the river,” boasted the warriors. “They cannot swim. Their powder will be wet. The fish will eat their bodies. The bones of the white men will lie upon every sandbar. Their flesh will fatten the buzzards. These white soldiers are not warriors. Their hands are soft. Their faces are white. One half of them are calico peddlers. The other half can only shoot squirrels. They cannot stand before men.”

Into this belligerent milieu rode Governor Harrison’s Delaware emissaries. Never long on self-restraint, Tenskwatawa at last succumbed to the war fever, evidently with renewed confidence in the inviolability of his own medicine. After all, he had hoodwinked Harrison and served up the Black Sun when the governor challenged him to produce a miracle. And later Harrison had naïvely provided him with food for his hungry followers. Perhaps the Master of Life would again favor Tenskwatawa at Harrison’s expense.

And so, while the young men gave themselves over to war dances, Tenskwatawa communed with the Master of Life — not, however, before declaring that he would burn the first American prisoner taken. For good measure, Tenskwatawa’s disciples roughed up the Delaware emissaries. Tecumseh’s injunction against provoking war was lost in the blustery bravado that pervaded Prophetstown.

Tenskwatawa’s abuse of the Delaware envoys exasperated Harrison. “I cannot account for the conduct of the Prophet upon any rational principle,” he wrote Eustis. “Nothing now remains but to chastise him, and he shall certainly get it.” On October 29, Harrison marched cautiously north from Fort Harrison. Rather than follow the old Indian trail up the

Disallowing the doubtful claim that the Prophet was behind the recent raids in the Illinois and Indiana territories, Harrison was clearly the aggressor. Perhaps mindful that political opponents would raise objections, he made a final attempt to avert bloodshed. Before crossing the Wabash River, he prevailed on the Delaware chiefs to send three or four men with another message to the Prophet, a mission that the Miamis endorsed and to which they also contributed two dozen chiefs and warriors.

Harrison’s terms were tantamount to a surrender of all for which the Shawnee brothers had strived. The Winnebagos, Potawatomis, and Kickapoos, who constituted three-quarters of the Prophetstown warrior population, were to return to their respective tribes. The Prophet was to deliver up the stolen horses Harrison assumed he had and turn over the “murderers of our citizens” or offer “satisfactory proofs that they were not under his control.”

The Delaware and Miami troop entered an Indian community roiled by internal conflict. The Potawatomis were divided between Shabbona’s small moderate faction and a larger contingent under Chief Wabaunsee, who had demonstrated his desire to kill white men by swimming out to an army keelboat on the Wabash two days earlier and tomahawking and scalping a crew member. The Winnebagos clamored for a fight, the Kickapoos were ready to take up arms if necessary, and Chief Roundhead’s contingent of Wyandots likely deferred to the Shawnee Prophet.

Confronted with factious followers, Tenskwatawa temporized. He expected Harrison to approach along the southeast side of the Wabash opposite the village. With the river as a barrier, Tenskwatawa hoped to stall him until Wyandot and Ojibwa warriors who were expected from the Michigan Territory arrived. He also agreed to a council. Unfortunately for him, however, the Delawares and Miamis were unaware that Harrison had crossed the Wabash.

Whatever powers the Master of Life may have granted Tenskwatawa, they clearly did not include the gift of omniscience. On the bleak and chill afternoon of November 6, Tenskwatawa was as startled as his most myopic follower when Indian scouts stumbled into Prophetstown to warn that the Long Knives were groping through the patchwork of leaf-choked ravines, soggy prairie, and barren autumnal forests southwest of the village. Warriors ran to occupy the log breastworks surrounding the town or spread out in the marshy pasture beyond to confront the enemy in the open. Women, children, and the elderly spilled

To the approaching Long Knives, the moment appeared ripe for an assault. To save his village, Tenskwatawa resorted to subterfuge. Certainly, he saw nothing immoral in deceit; to his way of thinking, the Americans had precipitated the conflict. “Who began the war?” he later asked a government official rhetorically. “Did not General Harrison come to my village? If we had come to you, then you might have blamed us, but you came to my village; for this you are angry at me.”

Out from Prophetstown at Tenskwatawa’s behest, several chiefs galloped toward Harrison’s army as it deployed in line of battle in tall prairie grass just 150 yards beyond the Indian fortifications. While the troops clutched their muskets and awaited the expected order to rush the village, Harrison held an impromptu council with the Prophet’s representatives. The Indians expressed surprise at Harrison’s rapid advance because the Delawares and Miamis had assured Tenskwatawa that Harrison would remain in place until he had the Prophet’s reply. The chiefs assured Harrison that Tenskwatawa wanted to avert bloodshed. Would the governor agree to meet with the Prophet the following day?

Much to the army’s dismay, Harrison accepted not only the offer of a council but also an Indian suggestion that he camp for the night on an oak-covered ridge three-quarters of a mile northwest of, and clearly visible from, Prophetstown. The interpreter Joseph Barron foresaw trouble. “I was mistrustful of the Indians from the moment of our arrival and told [Harrison] that their professions could hardly be depended on. I was averse to the place selected for encampment. I saw from appearances, and I knew from my long acquaintances with the Indians that they consider stratagems honorable in war.”

While Barron fretted and the Long Knives bedded down on the horizon, Tenskwatawa and the war chiefs faced off amid the lengthening shadows of what promised to be an exceedingly dark, cold, windy, and rainy November night. The issue at hand was whether to launch a surprise night attack or to confer with Harrison in the morning. Tenskwatawa had deceived the governor, not with respect to his own predilection, which in the actual face of the enemy leaned toward the pacific, but with respect to his failure to mention the belligerence of the war chiefs. Now their differences were made manifest. The Winnebagos demanded immediate action, and the war chiefs expected Tenskwatawa to provide the divine protection essential to victory.

Tenskwatawa was backed him into a corner and retired to commune with the Master of Life. After a suitable interval, he emerged from his wigwam, wearing a necklace of deer hooves and grasping a string of his sacred beans to announce a bevy

The battle must be fought that night, he announced. The Master of Life had conferred upon Tenskwatawa the power to sow chaos in the American lines. An impenetrable darkness would shield the Indians from the Long Knives, but Tenskwatawa would provide light “like the noontime sun” to guide the warriors and illuminate the stupefied Americans. His medicine also would disable American muskets. The Indian triumph would be as complete as had been the slaughter of Arthur St. Clair’s army north of Cincinnati two decades earlier.

Tenskwatawa “promised us a horse-load of scalps, and a gun for every warrior, and many horses,” recalled Shabbona. Every woman, moreover, “should have one of the white warriors to use as her slave, or to treat as she pleased.” Victory, however, was contingent on the warriors killing Governor Harrison. The Master of Life demanded his death. When he fell, the surviving soldiers “would run and hide in the grass like young quails,” insisted Tenskwatawa. “You will then have possession of their camp and all its equipage, and you can shoot the men with their own guns from every tree. But above all else, you must kill the great chief.”

Shabbona said that one hundred Kickapoo warriors were chosen to find and kill Harrison. They would know him by the white horse he customarily rode. Tenskwatawa retired with these men to the great council house to instruct them on their crucial mission. They were to crawl like snakes through the prairie grass, subdue the American sentries, then infiltrate the army camp until they reached Harrison’s tent. If American sentries spotted the warriors, they must “rush forward boldly and kill the great war chief of the whites.” If the Kickapoos failed to slay Harrison, the battle would be lost. This the Master of Life had told Tenskwatawa, and this, said Shabbona, “the Indians all believed.” Tenskwatawa retired to a low knoll near Prophetstown to pray — possibly for himself — and watch the forthcoming contest, leaving the execution of his plan to the war chiefs.

The Indian commanders led their warriors across the sodden prairie after midnight. A sharp wind whipped over the open ground. Rain fell cold and hard. The going was slow, gaps in the twisting files of warriors frequent. After making allowances for Tenskwatawa’s proposed rush on Harrison’s tent, the war chiefs agreed to attack in the usual fashion. The horns of an approaching Indian crescent would encircle the American camp. The Kickapoos, who led the march, would form the right horn, and the Winnebagos, who brought up the rear, would form the left. The Potawatomis and other Indian contingents would comprise the base of the crescent. After the Kickapoo infiltrators killed Harrison, the general assault would commence. The Indians would communicate across the battlefield with bone whistles and dried deer hoof rattles.

The Long Knives occupied a hollow, compact trapezoid on

Five hundred warriors neared the oak ridge, their medicine seemingly strong. The black rainclouds fulfilled one of the Prophet’s predictions, the American bonfires another. The flames would impede the Long Knives’ visibility and silhouette them to the oncoming warriors. But the Indians squandered their advantage. Overeager Kickapoos outpaced the other Indians. Coming up opposite Harrison’s southern flank at four-thirty a.m., they approached the American line while the Potawatomi, Winnebago, and mixed-tribal files were still struggling across the prairie. A disgusted Shabbona described the opening moments of the fight:

The men that were to crawl upon their bellies into camp were seen in the grass by a white man who had eyes like an owl, and he fired and hit his mark. The Indian was not brave. He cried out. He should have lain still and died. Then the other men fired. The other Indians were fools. They jumped up out of the grass and yelled. They believed what had been told them, that a white man would run at a noise made in the night. Then many Indians who had crept very close to be ready to take scalps when the white men ran all yelled like wolves, wild cats, and screech owls; but it did not make the white men run.

Shabbona was too hard on his Kickapoo brethren. The commander of the American sentries lost two men killed and several wounded in the opening moments of the battle. As the Kickapoos surged toward Harrison’s tent, the surviving sentries scattered, some tossing aside their muskets. Two companies of regulars nearly succumbed too, but Harrison escaped death by mounting a gray horse instead of the white horse the Indians expected him to ride. He shifted troops to blunt the

The Potawatomis came up on the left of the Kickapoos. The Winnebagos attacked Harrison’s northern flank fifteen minutes afterward. After negotiating stampeding cattle and horses from the American camp, the Shawnees, Wyandots, and other Indians opened fire on Harrison’s front line. By five a.m. the fighting had become general. Musket flashes lit the rain-streaked darkness, briefly revealing furtive Indian figures darting from tree to tree. Soldiers crumpled without the men nearest them even being aware they had fallen.

“The horrors attendant on this sanguinary conflict far exceed my power of description,” confessed a frightened regular. “The awful yell of the savages, the tremendous roar of musketry, the agonizing screams of the wounded and dying, mingling in tumultuous uproar, formed a scene that can better be imagined than described.”

It was often impossible to distinguish friend from foe. Crouching behind an oak, Shabbona watched a Delaware warrior easily dash past the soldiers to the one bonfire still burning; his musket had misfired, and he wanted to fix the gunlock by the firelight. A militiaman personally known to Shabbona raised his musket to dispatch the Delaware. Shabbona tried to shoot the Long Knife first, but a flag bearer unfurled his banner between the Potawatomi and his intended victim, blocking his shot. Then Shabbona heard the militiaman’s musket and saw the Delaware fall. “I thought he was dead. The white man thought so too and ran to him with a knife. He wanted a Delaware scalp. Just as he got to him the Delaware jumped up and ran away. He had only lost an ear.”

Shabbona, who wanted neither scalps nor glory, declined to rush the American lines. The Potawatomis were more determined. An army lieutenant opposing them recollected the difficulty of dislodging them: “The manner the Indians fought was desperate; they would rush with horrid yells in bodies upon the lines. Being driven back, they would remain in perfect silence for a few seconds, then would whistle on an instrument and commence the rush again, while others would creep up close to the lines on their hands and knees and get behind trees for their support.” Joseph Barron understood the significance of the brief pauses between onrushes: every time a warrior fell, the whooping leaders nearest him would cease their clamor.

As the darkness melted into a gray gunpowder-tinged twilight and Harrison’s lines held, the hiatuses grew more frequent. At seven a.m. sunrise put shadows to flight, and Indian morale weakened. “Our warriors saw that the Prophet’s grand plan had failed — that the great white chief was riding fearlessly among his troops in spite of bullets, and their hearts melted,” remembered Shabbona. “After

Shabbona perhaps overstated the impact of Governor Harrison’s survival on Indian resolve. Unlike the Ottawa chief Shabbona, many Potawatomis believed themselves on the verge of victory notwithstanding Harrison’s escape and instead blamed their failure to rout the American army on a lack of powder and lead. Most were down to their last rounds.

In any event, counterattacking infantrymen drove the Indians from the field at bayonet point. Saber-wielding dragoons pursued them into the marshes beyond the ridge. Slow runners among the warriors suffered a hard fate. An Indiana militiaman saw a wounded Indian stand up in the middle of the flooded prairie and stagger toward the timber bordering Prophetstown. A moment later a member of his company rushed down the ridge and shot the man dead. Then four brutal Kentucky volunteers crossed the prairie to claim the spoils of war. They divided the warrior’s scalp into four pieces, “each one cutting a hole in a piece, putting his ramrod through the hole and placing his part of the scalp just behind the first thimble of his gun near its muzzle. Such was the fate of nearly all of the Indians found dead on the battleground, and such was the disposition of their scalps.”

Tenskwatawa took no part in the Battle of Tippecanoe. On a hill well beyond the range of American bullets, he passed the early morning in incantations, enjoining the Master of Life to fulfill his promise of victory. As the warriors broke, Tenskwatawa fled into Prophetstown, where furious warriors denounced his impotent medicine.

The Winnebagos, long his most devoted followers, had suffered disproportionately high losses, including their war chief. Seizing Tenskwatawa, they brandished war clubs over his head and demanded to know why he had misled them into believing “that the white people were dead or crazy when they were all in their senses and fought like the Devil.”

Tenskwatawa thought fast. The blame for defeat, he said, rested not with him but with one of his wives, who had neglected to tell him that she was menstruating. All warriors understood that menstrual blood could nullify the strongest medicine of men; consequently, menstruating women were forbidden to handle sacred objects. But the foolish woman had not told Tenskwatawa, who permitted her to assist him in his prayers and manipulate his sacred strings of beans.

If the Winnebagos and other warriors would only rally, Tenskwatawa would clean his sacraments and again make medicine guaranteeing victory over the Long Knives. Spurning him but sparing his life for fear that killing the Prophet would bring divinely wrought death on themselves, the Winnebagos joined the general exodus from Prophetstown. Tenskwatawa also abandoned his sacred village, his reputation tarnished but not forfeited.

Harrison was content to allow the Indians to depart. He had been hurt badly, losing 62 dead and 126 wounded,

Indian casualties at Tippecanoe are difficult to calculate. They likely ranged from twenty-five to thirty-six dead and perhaps twice that number wounded. Harrison hastened to paint the battle as a stunning triumph – the legend would propel him to the Presidency thirty years later on the slogan “Tippecanoe and Tyler, too.” But dissenting voices emerged before the ink had dried on his report.

From Indian accounts of Tippecanoe, the Indian agent John Johnston concluded that “the governor has been outgeneraled by them, which is the more extraordinary when we consider his long acquaintance with their history and character.” Meeting with a Kickapoo chief who had seen action at Tippecanoe, Matthew Elliott, the venerable Indian superintendent at Amherstburg, Ontario, reported that the “Prophet and his people do not appear as a vanquished enemy.”

Weeks after the fight, Tecumseh would return from his trip to meet with the southern tribes disappointed but still intent on building a confederation of Indian nations to stand up to American encroachments. He and the Prophet would rebuild and try to expand their alliances westward, and seek more military supplies from the British. Indian outrage over Harrison’s Tippecanoe expedition would spur recruitment, and Kickapoo, Winnebago, and Potawatomi war parties began slogging through deep winter snows from the Mississippi to the Chicago River in search of American scalps to avenge their dead. Shortly after, friendly Fox Indians told their Indian agent that the Winnebagoes “were determined to perish or revenge themselves on the Americans for what Governor Harrison had done to their nation at the time they went to see the Prophet.”

The Shawnee brothers Tecumseh and “the Prophet” Tenskwatawa would emerge as truly transformative figures, able to unite adherents from more than a dozen tribes in confronting both the spiritual and physical menace the young American Republic posed to the Indian way of life. Their goal of a grand Indian alliance provides a window into the larger story of the turbulent early days of the United States, when American settlers spilled over the Appalachians and killed or intimidated Indians with a contemptuous disregard for treaty and law in their haste to exploit lands recently won from the British in the War of Independence. The violent treatment of the Indians and rampant lawlessness in the Old Northwest presaged the excesses

Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa stepped onto the stage just as the young American Republic flexed its expansionist muscles. Indisputably, Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa were the most significant siblings in American Indian history. Indeed, it is fair to conclude that the Shawnee brothers were also among the most influential siblings in the annals of America. Their story epitomized the disruption and disintegration of thousands of Indian families during this tragic and largely forgotten epoch in America’s march westward.