Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2021 | Volume 66, Issue 1

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2021 | Volume 66, Issue 1

Editor’s Note: Roy Morris Jr. is a contributing editor for MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History and the author of nine books, including a definitive history of the 1876 Presidential election, Fraud of the Century: Rutherford B. Hayes, Samuel Tilden, and the Stolen Election of 1876, in which portions of this essay first appeared.

Incumbent President Donald Trump, seeking to explain his reelection loss to Democratic candidate Joe Biden, tweeted three weeks after the 2020 election that it had been “the most corrupt election in American history.” There was no concrete proof of that charge, according to various state and federal courts, campaign officials and election certification boards.

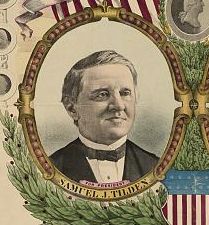

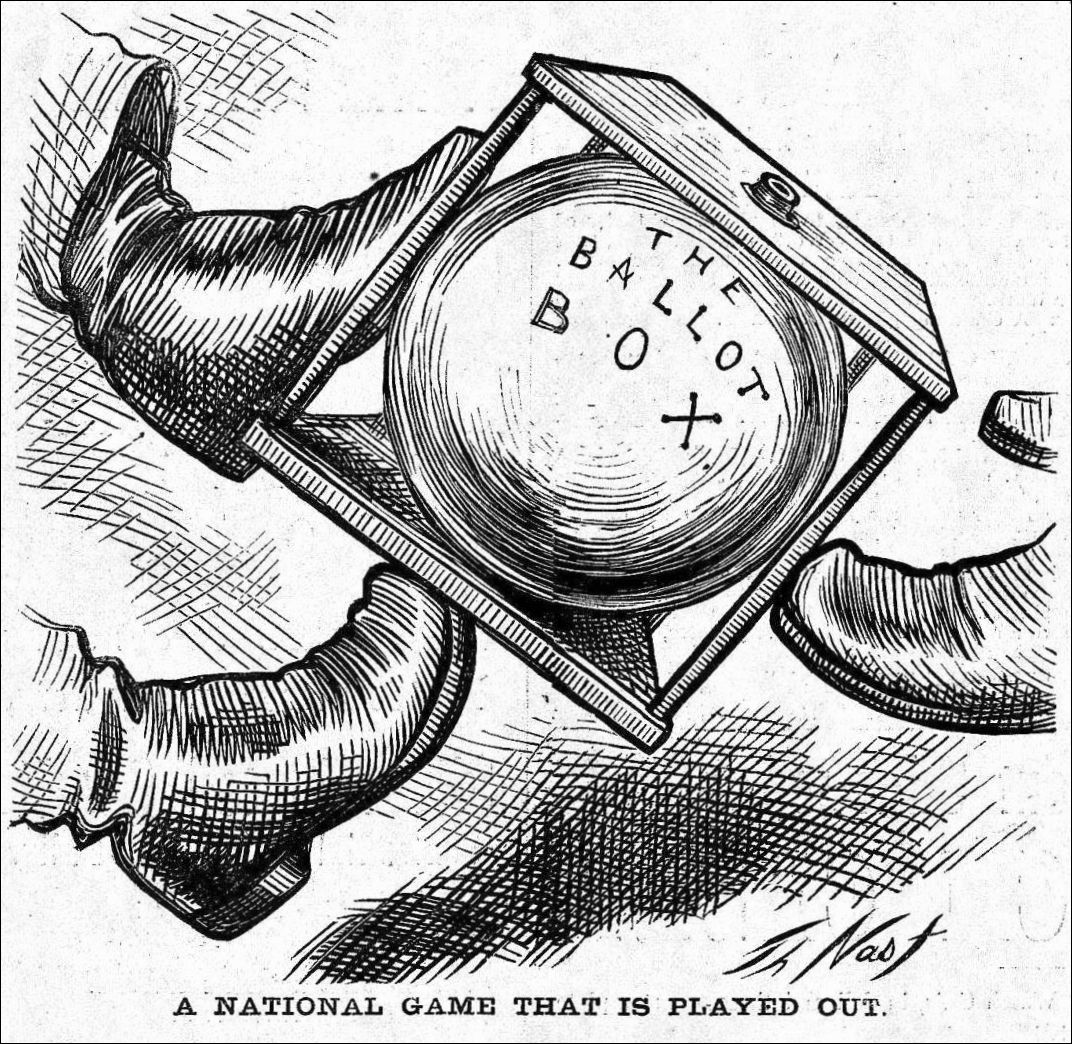

But even if Trump’s accusations had proven true, the 2020 election still could not have laid claim to being the nation’s most corrupt presidential election. That dubious distinction long since had gone to the 1876 presidential contest between Republican nominee Rutherford B. Hayes of Ohio and Democratic nominee Samuel J. Tilden of New York. No other presidential election even comes close.

Like the razor-thin election of 2000 between George W. Bush and Al Gore, the 1876 race also involved a few hundred votes in the state of Florida and was ultimately decided by the vote of a single Republican member of the U.S. Supreme Court. In both those elections there were charges of fraud, intimidation, lost ballots, and racism. Hordes of political operatives descended hungrily on the state, while the nation waited, anxiously if not breathlessly, for the winning candidate to be determined. When it was over, four months after election day, the candidate who probably had lost the election in Florida and definitely had lost the popular vote nationwide nevertheless was declared the winner, not just of Florida’s electoral votes but of the presidency itself.

The result was a singularly sordid presidential election, perhaps the most bitterly contested in the nation’s history, and one whose eventual winner was decided not in the nation’s multitudinous polling booths but in a single meeting room inside the Capitol, not by the American people en masse but by a fifteen-man Electoral Commission that was every bit as partisan and petty as the shadiest ward heeler in New York City or the most unreconstructed Rebel in South Carolina. It was an election that did little credit to anyone, except perhaps its ultimate loser.