Authors:

Historic Era: Era 7: The Emergence of Modern America (1890-1930)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2021 | Volume 66, Issue 1

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 7: The Emergence of Modern America (1890-1930)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2021 | Volume 66, Issue 1

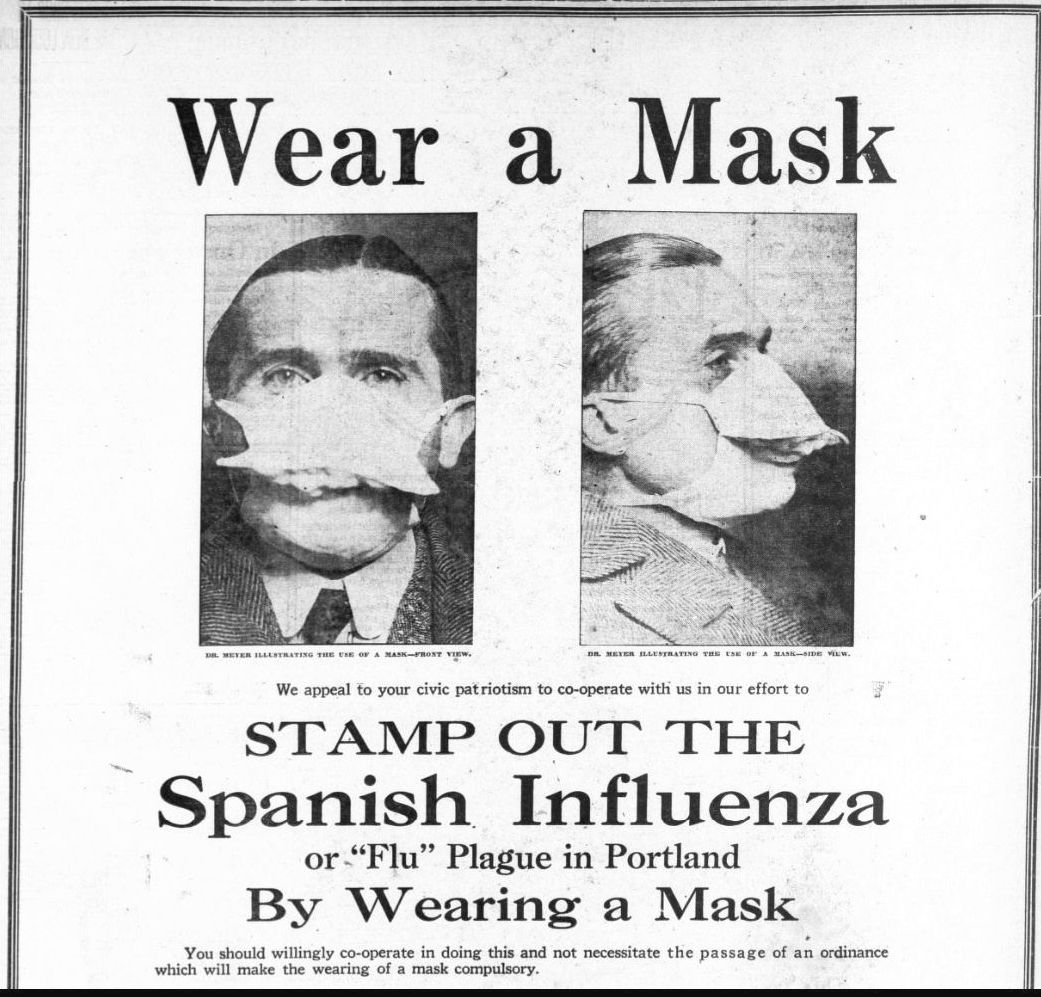

We have become all too familiar in the last year with face masks, social distancing, lost income, empty streets, and the gnawing fear of being the next to be stricken. Recently, our downtowns cities have resembled London during the Great Plague — “the streete thin of people, the shops shut up, and all in mournful silence, as not knowing whose turne might be next,” as John Evelyn penned in his diary in 1665.

The reality in 2020 may have shocked most people, but it's not a new phenomenon in America. In fact, a pandemic has appeared in almost every generation since the earliest settlements on the continent.

Many of these pandemics profoundly changed society. Smallpox enabled Cortés to conquer Mexico and its vastly larger Aztec army. A few years later, it arrived in New England, carried by a European sailor shipwrecked on Cape Cod, as Charles Mann wrote in "A Pox on the New World" in American Heritage. The terrible disease quickly spread among Native American tribes, causing high fever, chills, and scarring of the skin in those who survived. Indians “died in heapes, as they lay in their houses,” the merchant Thomas Morton recalled.

In evolutionary history, the native populations on the American continents had few pandemic diseases before Europeans arrived— no smallpox, influenza, measles, or malaria. So there was little inherent immunity from these new diseases, or understanding about how they spread. Sometimes individuals who seemed healthy but were infected would flee to neighboring villages, carrying the disease with them.

As smallpox crossed the continent, it wiped out entire Indian tribes, an estimated 70 percent of the total population of North America. Anger over the introduction of disease fueled Indian animosity against white settlers. But the reduction of native populations in New England enabled European settlements to survive in the decades that followed these pandemics.

Professor Alfred W. Crosby of the University of Texas also wrote about the sad history of smallpox and Native Americans in American Heritage. The epidemic “struck the coast of New England, devastating the tribes like an autumnal nor’easter raking leaves from the trees.” One colonist informed the Wampanoag tribe that Europeans had the plague as their ally, in addition to gunpowder. “The God of the English has it in store, and could send it at his pleasure, to the destruction of his or our enemies.”

The Great Plague in England killed an estimated 100,000 people in 1665 and 1666, including