Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

November 2020 | Volume 65, Issue 7

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

November 2020 | Volume 65, Issue 7

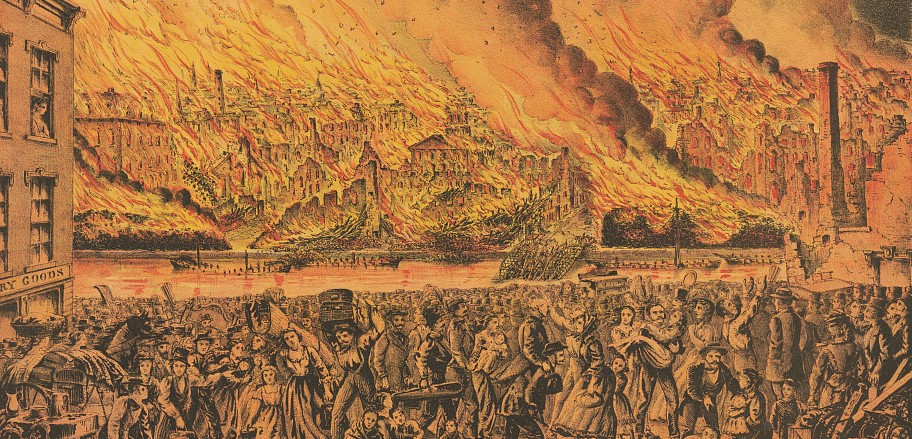

Editor’s Note: On October 8, 1871, the Great Chicago Fire destroyed close to three square miles of the city, took an estimated 300 lives, and left some 90,000 homeless. Surprisingly, there has not been a major, carefully researched book on the fire until Chicago's Great Fire: The Destruction and Resurrection of an Iconic American City, from which this is excerpted and adapted. Author Carl Smith is a professor emeritus of English, American Studies, and history at Northwestern University.

Patrick and Catherine O’Leary lived with their five children—two girls and three boys, ranging from a fifteen-year-old to an infant—about three quarters of a mile south of the Saturday Night Fire, on the north side of DeKoven Street, some two hundred feet east of Jefferson Street. A local reporter described the neighborhood, one of the most densely populated sections of the city, as “a terra incognita to respectable Chicagoans,” packed with “one-story frame dwellings, cow-stables, corn-cribs, sheds innumerable; every wretched building within four feet of its neighbor, and everything of wood.”

Catherine O’Leary was about forty, and Patrick O’Leary a few years older. They were both immigrants from Ireland, he from County Kerry in the southwest and she from adjoining County Cork. They married before departing for America in 1845, at the onset of the potato blight that starved the country and killed or drove out more than 20 percent of the population over the next half dozen years. They had first lived in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, where Patrick had enlisted to serve in the Union Army.

Patrick was an unskilled laborer, earning perhaps $1.50 to $2.00 a day when he found work. Catherine kept house and conducted a small dairy business in the neighborhood. By this time most milk arrived by train from the surrounding countryside, but it struck no one as unusual that a family, whether wealthy or poor, might keep farm animals well within the city limits. Catherine O’Leary sheltered her four cows, a calf, and the horse that pulled her milk wagon in the barn behind their home. The livestock was an important source of income in which she and Patrick had made a significant investment. She had taken delivery of two tons of timothy hay for the animals the day before. The O’Learys had also recently received and stored in the barn a supply of wood shavings and coal for cooking and to keep them warm in colder days ahead.

A person of generous inclination might call the O’Leary home a cottage, but it was not much more than a ramshackle shanty, sixteen feet wide and about twice that deep. Like thousands of others throughout the city, it consisted of a frame made of two-by-fours covered