Authors:

Historic Era: Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

October 2020 | Volume 65, Issue 6

Authors: David S. Reynolds

Historic Era: Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

October 2020 | Volume 65, Issue 6

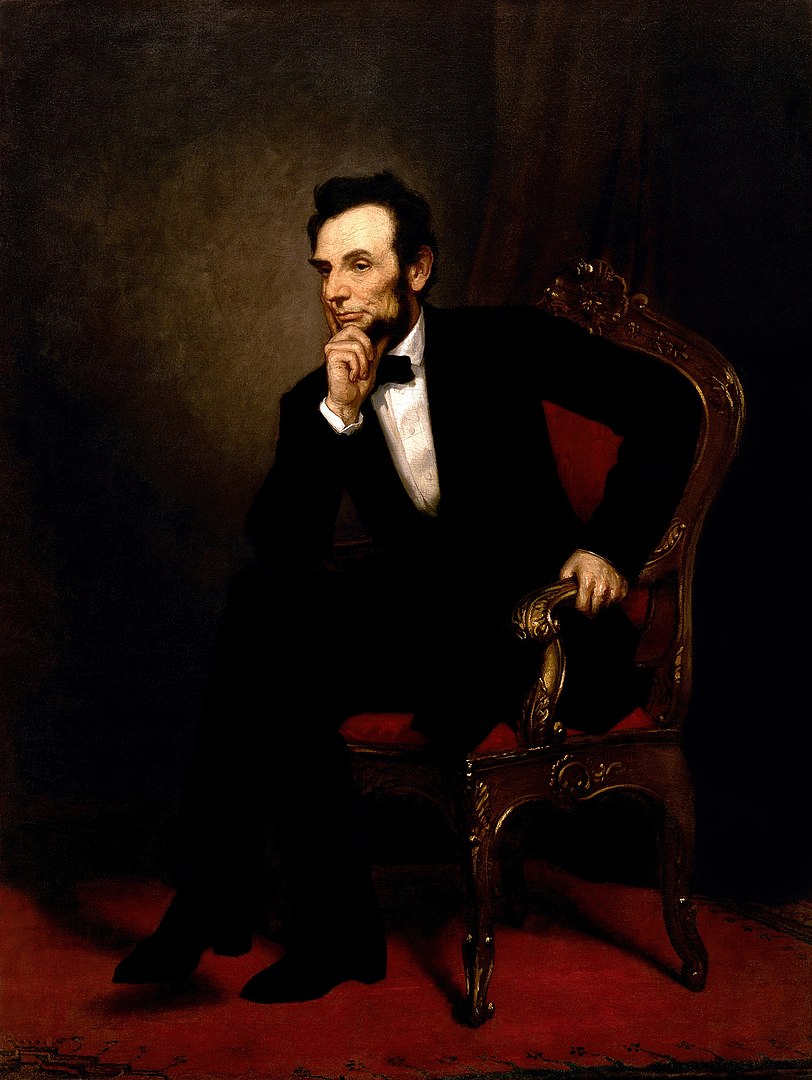

Editor's Note: David S. Reynolds is a Distinguished Professor at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York and the author of 15 books including first-rate biographies of Walt Whitman, John Brown, and Harriet Beecher Stowe. His latest is Abe: Abraham Lincoln in His Times, an ambitious and wide-ranging biography connecting Lincoln to his cultural environment in antebellum America. Publishers Weekly calls the book “magisterial and authoritative."

What makes a president great? How do we judge the character of candidates for high office? Those questions have been transcendent for American voters since the earliest days of our republic. And, since most people believe that Lincoln was our greatest president, it’s worth examining what it was that made him great.

Lincoln gained many of these traits through reading. Today, psychologists such as Geoff Kaufman at Dartmouth College point out that when we read about and identify with characters in fiction, we tend to subconsciously adopt their behavior. Lincoln proves that the same is true of nonfiction as well – his early reading exposed him to the role models of George Washington and Benjamin Franklin. And he absorbed core values from the Bible and Aesop’s Fables, and learned from reading James Riley that America had the finest political system in the world, but it was also stained by the worst form of oppression.

Lincoln’s schooling experience was typical for a boy growing up on the Kentucky-Indiana frontier. His total time in school, he reported, was less than one year. Abe attended five schools for short terms, two in Kentucky before he turned seven and three in Indiana at the ages of eleven, thirteen, and seventeen.

Schools on the frontier at the time were often windowless and dirt-floored, single-room log structures. A school term customarily lasted two or three months and was scheduled not to conflict with the planting and harvesting seasons, when children were needed for farm work.

However, in nineteenth-century America a sound education could be found outside the classroom as shown by the experiences of Frederick Douglass, who had no formal schooling yet became one of the century’s most eloquent communicators, or Walt Whitman, the great poet who left school at eleven. This was the case with Lincoln. He absorbed the cultural energies of the frontier, and read books that helped shape his character. He was an attentive reader, and little was lost on him. He often repeated passages aloud and wrote them down whenever he could.

When we survey these eclectic influences — to which can be added newspapers, which he began reading in Indiana in the 1820s — we see his mind was fed early on by all kinds of sources, high and low, sacred and secular. Absorbing

That Abe’s openness to his cultural surroundings laid the basis for his character was described by the Illinois attorney John W. Scott:

The books the young Lincoln read broadened him immeasurably. In the 1860 campaign biography by John Locke Scripps, authorized by Lincoln, seven books from Lincoln’s early years are highlighted as having been especially formative: Thomas Dilworth’s Spelling-Book, the Bible, Aesop’s Fables, Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, Mason Locke Weems’s The Life of Washington, Benjamin Franklin’s Autobiography, and James Riley’s Narrative of the Loss of the American Brig Commerce.

Other books important to the young Lincoln included William Scott’s Lessons in Elocution, The Kentucky Preceptor, Noah Webster’s The American Speller, The Seven Voyages of Sinbad, Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, and Lindley Murray’s The English Reader.

One of the earliest books he read, Thomas Dilworth’s Spelling-Book, was heavily didactic; it taught reading and spelling through preachy poems, biblical passages, and fables followed by interpretations. Each virtue points humans in a definite direction (lying and atheism lead toward hell, honesty toward heaven, and so on). But its didacticism sometimes contains seeds of radicalism.

The first lesson in the book reads: “No man may put off the laws of God; / My joy is in his law all the day” — a seemingly tame statement, yet one that presaged what for Lincoln and many other Americans would become one of the most controversial concepts of the pre-Civil War decade: the higher law, by which disobedience to human laws was deemed justified or even required if these laws were found to be in violation of God’s law.

Other textbooks Lincoln read were more far-reaching than Dilworth’s. For example, Williams Scott’s Lessons in Elocution included literary passages such as the soliloquy of Hamlet’s uncle on the murder of his brother (“Oh! My offense is rank; it smells to heaven”), which Lincoln would spontaneously recite during his presidency. Another source of memorable passages was Lindley Murray’s English Reader, which Lincoln later called “the best school-book ever put into

Aesop’s Fables proved a fertile source for him. The story about the strength of bundled sticks prompted Lincoln to use the image later in a political circular when encouraging his fellow Whigs to act in unison rather than separately. The fable about the lion who surrenders his teeth in order to win the woodman’s daughter and then is beaten to death by the woodman was cited by Lincoln when he refused to make concessions to the Confederacy that he knew would weaken the North. Aesop’s tale about two whites who futilely tried to rub away a black man’s skin color reminded Lincoln of Northerners who coldly de-emphasized the African American as a consideration in the war.

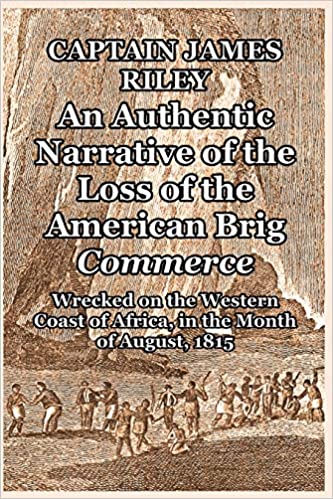

Lincoln’s early reading exposed him to the core values of American democracy. Take one of his favorite books, James Riley’s Narrative of the Loss of the American Brig Commerce. First published in 1817, Riley’s book went through twenty-four editions and enjoyed a lively sale. It was one of the last — and among the most famous — of the so-called Barbary captive narratives that had been written regularly since 1680. These narratives, some fictional and others, like Riley’s, based on fact, involved American or British sailors who were captured off the Barbary Coast in northern Africa, taken captive, and held in slavery by their Muslim captors.

Riley makes strong statements against American slavery. Although he portrays the Barbary masters as frequently harsh toward their white slaves, whom they call “Christian dogs,” he points out the inconsistency of America, supposedly the land of equality, holding more than a million black people in slavery. While Riley expresses appreciation for “the blessings of my native land, where political and moral institutions are in themselves the very best of any that prevail in the civilized portion of the globe,” he adds, “and yet, strange as it must appear to the philanthropist, my proud spirited and free countrymen still hold a million of the human species in the most cruel bonds of slavery, who are kept at hard labor and smarting under the savage lash of inhuman mercenary drivers,” and enduring “the miseries of hunger, thirst, imprisonment, cold, nakedness, and even tortures.”

Riley’s dual message — America has the world’s finest political system, but its democratic ideals are betrayed by the worst form of oppression — came to be shared by Lincoln, who would famously hail his nation as “the last best hope of earth” and yet loathed slavery so much that he chose civil war over tolerating its spread.

Lincoln also encountered antislavery passages in other books he read in his youth. The

It is likely that the young Lincoln, weaned in an antislavery Baptist sect, already had intimations of his later antislavery interpretation of the nation’s founding documents, which he appears to have read in his mid-teens. The Statutes of Indiana (1824), a law book he borrowed from his friend David Turnham, included as prefaces the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. One of Lincoln’s main achievements as a politician would be to combine the spirit of these three founding texts in a way that convincingly positioned the antislavery argument within the boundaries of the American system.

Crystallizing the arguments of other antislavery politicians, Lincoln merged the concept behind the Northwest Ordinance — which forbade the extension of slavery in the Western territories north of the Ohio River — with the Declaration’s pronouncement of human equality and the Constitution’s protection of human rights. This antislavery constitutionalism, which he presented most persuasively in the Cooper Union Address in 1860, was grounded in his meditations on the Founders and their ideals as a teenager in Indiana.

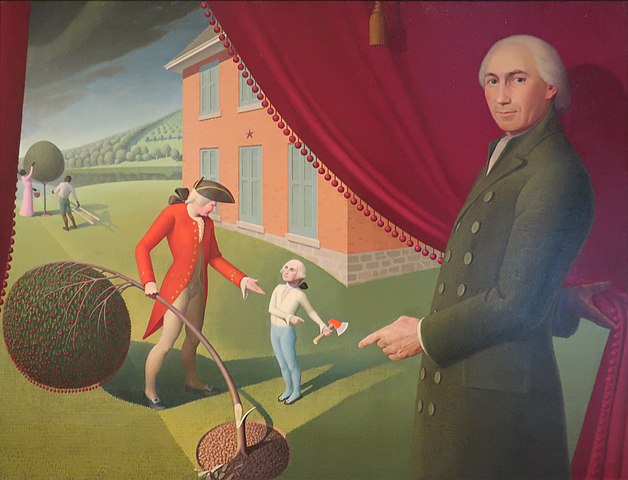

Lincoln’s interest in the Founders was fanned by The Life of George Washington by the Maryland-born preacher and bookseller Mason Locke Weems. In February 1861, when addressing the New Jersey Senate on a stop on his trip east to assume the presidency, he recalled that “a way back in my childhood, the earliest days of my life being able to read, I got hold of a small book, . . . Weems’ Life of Washington. I remember all the accounts there given of the battlefields and struggles for the liberties of the country, especially ‘the crossing the river’ and the contest with the Hessians.”

First published in 1800, Weems’s Washington appeared in expanded form in 1806, containing some new “very curious anecdotes,” including the apocryphal story about the cherry tree. This revised book went through many editions before Weems’s death in 1825. Lincoln read the 1809 edition, with its “curious anecdotes,” and its illustrative woodcuts. Lincoln could not know that Weems had made up the story about the young George confessing to his father that he was responsible for cutting down the cherry tree.

But patriotism and candor were not the only virtues Lincoln found

Lincoln, too, was known for his strength and sports skills. He could lift heavier weights, throw objects farther, and jump longer than any of his companions. He once mused about who would be the victor if he wrestled with Washington. When reminded that a descendant of Washington’s had reported that the first president “was perhaps the strongest man of his day. . . . And that in his youth he was a frontier wrestler, having never been thrown,” Lincoln remarked, “I can outlift any man. . . . When I was young, I never was thrown.” He added wryly: “If George was loafing around here now, I should be glad to have a tussle with him, and I rather believe that one of the plain people of Illinois would be able to manage the old aristocrat of old Virginia.”

The aristocrat of old Virginia may have been a muscle man, in the view of biographers, but he was also the model of evenhandedness — an attribute Lincoln aspired to. Another bestselling biography of Washington that Lincoln read was the 1807 book by David Ramsay, who portrayed the Founder as the epitome of equanimity. “He had religion without austerity,” Ramsay wrote, “dignity without pride, modesty without diffidence, courage without rashness, politeness without affectation, affability without familiarity. . . . [He was] a lover of order, systematical and methodical.” Another bonus of Ramsay’s biography was the inclusion of Washington’s will, in which he manumitted the slaves on the decease of his wife — an antislavery gesture on the part of the First American that fed into Lincoln’s view that the Founders desired the eventual extinction of the South’s peculiar institution.

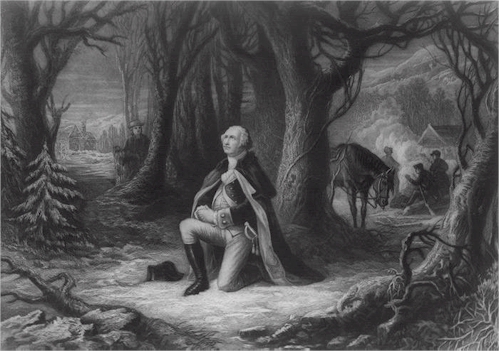

Washington’s Farewell Address was also included in Ramsay’s book. In his speech, Washington emphasized the paramount importance of preserving the American union, which, he saw, was threatened by warring factions and party divisions. A unifying force that Washington appealed to was religion. “This unity of government which constitutes you one people,” he declared, must be anchored in religion. Otherwise, he asked, how could oaths taken in courts or public hearings have credence? How could checks and balances work if amorality reigned? “Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity,” he said, “religion and morality are indispensable supports.”

The Washington that Lincoln and his contemporaries read about did not only promote religion publicly; he observed it privately as well. Ramsay writes of the first president: “The friend of morality and religion, he steadily attended on public worship; encouraged and strengthened the hands of the clergy; and in all his public acts made the most respectful mention of Providence. In a word, he carried from private life into his public administration the spirit of piety, a dependence upon the supreme governor of the universe.”

Weems’s Washington is even more pious than Ramsay’s. In Weems’s biography, the young George is taught to believe in God by his father, who in a crucial scene teaches him that all the beautiful and useful things in the world did not come by chance but were of divine origin. It was “at that moment that the good Spirit of God ingrafted upon [George’s] heart that germ of piety, which filled his after life with so many of the precious fruits of morality.”

As president, Weems’s Washington never misses church, no matter how pressing the national business is. As for the Farewell Address, that, Weems writes, was “about the length of an ordinary sermon” and “may do as much good to the people of America as any sermon ever preached, that DIVINE ONE on the mount excepted.” Washington’s death elicits from Weems a gush of piety even more rapturous than Harriet Beecher Stowe’s description of the death of the young Eva St. Clare in Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Washington is escorted heavenward: “Swift on angels’ wings the brightening saint ascended; while voices more than human were heard (in fancy’s ear), warbling through the happy regions, hymning the great procession, towards the gates of heaven.”

Weems’s and Ramsay’s readers could not know what historians have discovered: Washington was not nearly as devout as many Americans of that time wanted to believe. Although he was an Episcopalian, his church attendance was irregular, and he rarely, if ever, took communion. He was extremely private about his religious views, which seem to have been closer to deism than to Christianity. On his deathbed, he did not call for a member of the clergy. It is unclear if he believed in an afterlife.

But he did believe in the utility of religion as a means of fostering morality and unity in America. He saw the need of the religious spirit for supporting democratic institutions, and he did not privilege one religion or denomination over another.

In this regard, he was like another Founder with whom Lincoln was deeply familiar, Benjamin Franklin. In Indiana, the twelve-year-old Lincoln, at his father’s request, reportedly read aloud to the family sections of The Life of Dr. Benjamin Franklin, Written by Himself,

Franklin wrote a deistic pamphlet and won over two close friends to his newfound philosophy. However, he soon discovered that deism opened him up to sharp criticism, and he decided that, as he put it, “this doctrine, though it might be true, was not very useful.” After giving out some copies of his freethinking pamphlet, he destroyed the remaining ones and said little overtly about deism for the rest of his life.

Although Lincoln, like the founders, was a rationalist who viewed church religion skeptically, he could look to them for moral and spiritual guidance. After all, Franklin, Jefferson, and Thomas Paine, had performed good works and had founded a mighty nation. And they were religious, in their own way. Although Jefferson as president carefully respected the separation of church and state, even he invoked “a benign religion, . . . acknowledging and adoring an overruling providence” in his 1801 inaugural address, which was included in an anthology that the young Lincoln read, The Kentucky Preceptor. And Washington, despite his guardedness about his own faith, nonetheless insisted on religion as a necessary support for democratic institutions.

Lincoln, in this respect, was like Washington—secretive about his own religion, but innovative and insistent on the uses of religion in American public life. Like a deist, he rarely took sides among religions, and his tolerance of many faiths was remarkable. For him, as for Washington, the religious spirit held the potential of stabilizing and unifying a fragmented nation.

Lincoln also resembled Franklin, who rejected the Calvinistic faith of his childhood, turned for a time to deism, and then espoused a pragmatic religion based on good deeds. In one of the rare moments that he discussed his private beliefs, Lincoln declared he would join a church if he found one whose only requirement was to follow the Golden Rule. This was essentially the view of Franklin and the other Founders, who escaped the confines of a single church without abandoning religion altogether.

Franklin, who had risen from humble beginnings to the highest realms of achievement, established in his autobiography the self-made man stereotype that by Lincoln’s time had become part of the nation’s cultural fabric. Franklin’s autobiography stood as a how-to guide

How did Lincoln measure up to these virtues? Six of them — Moderation, Temperance, Tranquility, Humility, Sincerity, and Justice — were ones for which Lincoln undeniably deserved high marks. Franklin’s statement about Moderation, “Avoid extremes,” defined Lincoln more clearly than any other conceivable phrase. As a Northerner from a Southern background who could claim both Puritan and, in his mind, Cavalier roots, Lincoln was by nature prepared to take a middling course that, in the end, proved to be the salvation of the nation. He could take his place securely in the center because he had a genuine understanding of both antislavery and proslavery extremists that led him to see that radical militancy could, if carried through, destroy the Union.

Industry, another of Franklin’s virtues, was demonstrated in Lincoln’s youth. Lincoln once said that his father taught him how to work but not how to enjoy it. The work he referred to here was manual labor — the kind of work frontiersmen and farmers did. But felling and mauling trees had a positive impact on Lincoln’s career, for these frontier jobs fed the popular image of Lincoln as the Illinois Rail-splitter, which helped get him elected president.

Even when he shirked manual labor in his youth, Lincoln was preparing for the future. Dennis Hanks declared, “Lincoln was lazy — a very lazy man — he was always reading — scribbling — writing — ciphering — writing poetry &., &.” In his account of Industry, Franklin advises, “[B]e always employed in something useful: cut off all unnecessary actions.” But the activities that Hanks saw as signs of laziness were actually very useful to Lincoln in the Franklinian sense. Just as learning to read was Frederick Douglass’s path to freedom and influence, so the young Lincoln’s pursuit of reading, ciphering, and writing poetry lay behind his later success in redefining the nation through eloquent, well-reasoned language.

His reading spurred his precocious ambitiousness. In Dilworth’s Spelling-Book he would have read, “He that will not help himself, shall have help from nobody.” In Scott’s Lessons in Elocution, he received similar counsel: “Whatever you pursue, be emulous to excel.” Lincoln took such advice to heart. When he was a teenager in Indiana, a neighbor, Elizabeth Crawford, scolded him for teasing girls and asked, “What do you Expect will become of you?” She recalled his confident reply: “‘Be Presdt of the US,’ promptly responded Abe . . . He said that he would be Presdt of the US told my husband so often — Said it jokingly — yet with a Smack of deep Earnestness in his Eye & tone.” William Herndon confirmed, “He was always calculating,

Lincoln’s record on Franklin’s virtue of Tranquility was mixed. Periodically, Lincoln erupted in anger — as a lawyer against churlish or ungrateful clients, as president against visitors who pressured him too hard for favors, and so on. What was most remarkable, however, was how he kept calm in situations that would have traumatized the average person. “Through all his life, and through all the unexpected and stirring events of the rebellion,” his private secretaries Hay and Nicolay noted, “his personal manner was one of steadiness of word and act.” Had Lincoln been emotionally unstable, Herndon added, he “would have lost — lost, all, all.” Fortunately for the nation, he was practical, patient, and cool.

Humility, another of Franklin’s virtues, became one of Lincoln’s signature qualities. In his first speech as a fledgling Illinois politician, as a friend recalled, the ungainly, simply-attired Lincoln announced, “Gentlemen and citizens. I assume you know who I am. I am humble Abraham Lincoln.” Like Franklin’s self-effacing Poor Richard, the rough-hewn Lincoln appealed to the American masses because he seemed to be on their level.

Lincoln was also honest in the sense of Franklin, who wrote of Sincerity: “Use no hurtful deceit.” Lincoln’s sincerity, in a pragmatic Franklinian sense, cannot be denied. Lincoln seemed like an anomaly: a frontiersman, lawyer, and politician with an indisputable air of honesty. The Illinois attorney Samuel C. Parks, identifying as Lincoln’s major trait “integrity in the longest sense of that term,” noted, “I have often said that for a man who was for a quarter of a century both a lawyer & a politician he was the most honest man I ever knew.” And he was honest from an early age, as was testified by his stepmother, who recalled, “He never told me a lie in his life — never Evaded — never Equivocated never dodged.” It was no surprise that the masses came to know him as Honest Abe.

In heeding justice whenever he could, Lincoln revealed his debt to the Scottish Common Sense philosophy, to which he was exposed in his youth. Having emerged from Edinburgh in the early eighteenth century and having spread to England, the Continent, and America, Scottish Common Sense taught that every person is born with a conscience — a knowledge of the distinction between right and wrong — and that through reason and the exercise of virtue one could follow that conscience. The young Lincoln got a heavy infusion of Common Sense philosophy from his early reading, not only from Franklin but also from William Scott’s Lessons in Elocution and Lindley Murray’s Reader, which contain pieces by the Edinburgh thinker Hugh Blair (1718?1800) and others of the Common Sense school. A typical passage in

What was truly unusual about Lincoln was that he firmly distinguished between right and wrong without maintaining that he was following direct commands from God. He realized that the idea that God takes sides leads to narrowness and, at worst, bloodshed. It was important, in his view, for humans to believe in a Divine Being but equally important for them not to pretend to understand God’s purposes.

Lincoln has often been called a fatalist — an accurate assessment, as long as we understand that he was not a pessimistic one. His was not the fatalism of, say, Jonathan Edwards, who insisted that most humans were predestined to hell — a notion Lincoln found repulsive — nor was it the gloomy determinism of later American authors, such as Frank Norris or Theodore Dreiser, who saw humans as pawns amid material forces.

Lincoln’s view was more in line with the optimistic fatalism he found in Alexander Pope’s “An Essay on Man,” a poem that was included in his childhood anthologies and that long remained a touchstone for him. As president, Lincoln once told a British visitor that he thought “An Essay on Man” “contained all the religious instruction which it was necessary for a man to know.” The president asked the visitor if knew any wiser lines than the concluding ones of the poem’s First Epistle, which Lincoln recited from memory:

"All Nature is but art, unknown to thee;

All chance, direction, which thou canst not see;

All discord, harmony not understood;

All partial evil, universal good:

And, spite of pride in erring reason’s spite,

One truth is clear, whatever is, is right."

When the visitor praised the beauty of the passage, Lincoln smiled and said, “Yes, that’s a convenient line, too, that last one. You see, a man may turn it, and say, ‘Well if whatever is is right, why then, whatever isn’t must be Wrong.” Lincoln laughed heartily, and his visitor joined in.

Beneath the humor lay Lincoln’s sober recognition that right and wrong were, after all, relative. The best one could do, he realized, was to attempt to align good works with one’s sense of justice, without ever being assured that one knew God’s plan. In Pope’s view, “direction,” “harmony,” and “universal good” were there, even though they were hidden from “erring reason.”