Authors:

Historic Era: Era 7: The Emergence of Modern America (1890-1930)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

September 2020 | Volume 65, Issue 5

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 7: The Emergence of Modern America (1890-1930)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

September 2020 | Volume 65, Issue 5

Editor's Note: Susan Ware is a historian, general editor of the American National Biography, and editor of the biographical dictionary, Notable American Women. Among her books is Why They Marched: Untold Stories of the Women Who Fought for the Right to Vote (Harvard University Press), from which this essay is adapted.

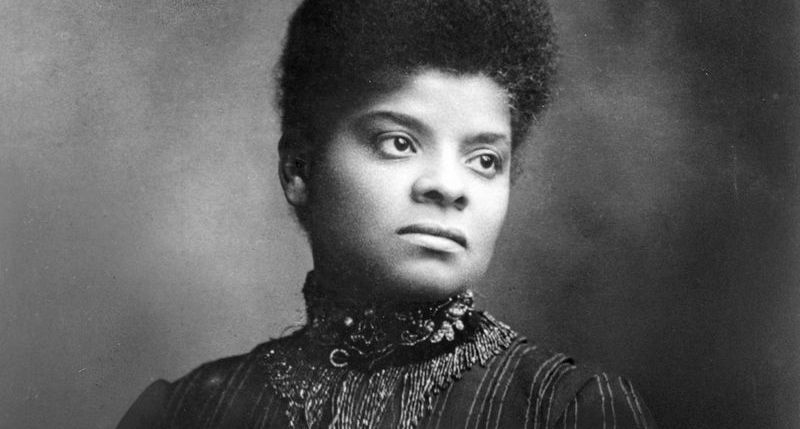

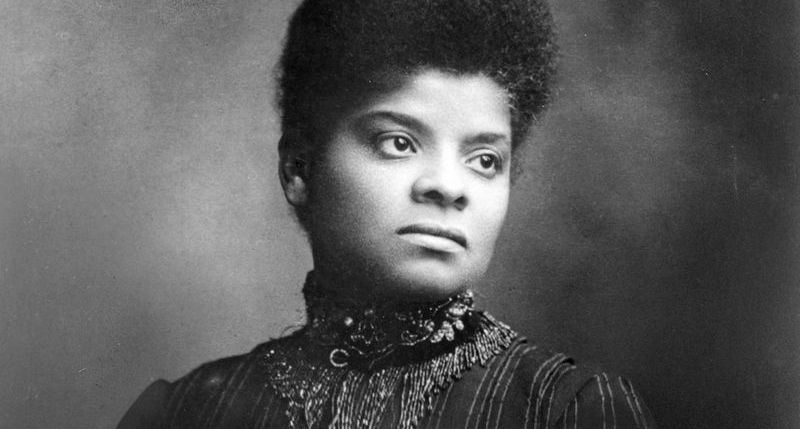

In the first six months of 1913, Illinois was a hotbed of suffrage activism, and Ida Wells-Barnett wanted to make sure that African American women were part of the action.

Despite being a longtime member of the Illinois Women’s Suffrage Association, she had not previously been able to drum up much interest on the question within Chicago’s growing black community. But now that the Illinois legislature was considering the law to grant presidential and municipal suffrage to women, things were different. “When I saw that we were likely to have a restricted suffrage.” Wells Barnett recalled, “and the white women of the organization were working like beavers to bring it about, I made another effort to get our women interested.”

On January 30, 1913 she founded the Alpha Suffrage Club, the first African American suffrage organization in Chicago. Two months later, at a march timed to protest President Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration, she challenged the racism of the white-led national movement head-on — and she prevailed.

Ida Wells-Barnett was no stranger to controversy. Born a slave in Holly Springs, Mississippi during the upheavals of the Civil War, she spent the rest of her life fighting for full citizenship, both as an African American and a woman. After a yellow fever epidemic killed her parents and a younger sibling in 1878, she dropped out of school and became a teacher to support her family, even though she was only sixteen years old. Seeking broader opportunities, she relocated to Memphis, where she became a journalist.

Ida B. Wells’s first experience in challenging discrimination came in 1883, when she was forcibly evicted from the “ladies” car on a Chesapeake & Ohio train and forced to relocate to the much less commodious “colored” car. Indignant at her treatment, she sued the railroad company, claiming she was entitled to ride in the ladies’ car because she had purchased a full-fare ticket specifically designated for it. She won an initial settlement from the railroad company, but it was later overturned. Confirming the deteriorating climate for African American rights, the Supreme Court upheld the practice of Jim Crow segregation in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896.

of losing revenue to Black-owned businesses. " data-entity-type="file" data-entity-uuid="37826b10-d588-4723-82be-225c63d9875a" height="451" src="https://www.americanheritage.com/sites/default/files/inline-images/Lynch_Laws_original.jpg" width="297" loading="lazy">

Ida B. Wells is best known for her anti-lynching activism. Her epiphany occurred in 1892 in Memphis, where she had become part owner of a newspaper called the Memphis Free Speech. When three black men were lynched by a white mob, Wells exposed the real reason for the racial violence in her pamphlet Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases: successful black shopkeepers posed an economic threat to white businessmen.

She also challenged the claim that black men were lynched because they raped white women, pointing out that some white women voluntarily engaged in sexual relations with black men.

In retaliation for such inflammatory statements, the office of her newspaper was trashed, and she was basically run out of town. Several years later, she relocated to Chicago, where she married the lawyer Ferdinand Barnett and had four children. She lived in Chicago for the rest of her life.

Anti-lynching was but one of the many crusades for justice that Ida Wells-Barnett (as she was now known) took on. In 1893, she publicly challenged the organizers of the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago for excluding the contributions of African Americans. In 1894, she attacked the temperance leader Frances Willard for making racist statements about black men’s moral character and demanded, without success, that the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union make anti-lynching part of its broad reform agenda.

In 1910, she organized the Women’s Second Ward Republican Club on Chicago’s South Side, “to assist the men in getting better laws for the race and having representation in everything which tends to the uplift of the city and government.” She also founded a South Side settlement house called the Negro Fellowship League. Three years later, she founded the Alpha Suffrage Club.

Even though African Americans at the time were overwhelmingly associated with the Republican Party, the Alpha Suffrage Club was nonpartisan. Its primary goal was to educate African American women about the duties and responsibilities of citizenship and voting. As Wells-Barnett admitted, the club often started from scratch: “If the white women were backward in political matters, our own women were even more so.” The goal was to make African American women feel more comfortable in the realm of politics and then to “use the vote for the advantage of ourselves and our race.”

One of the Alpha Suffrage Club’s first tasks was to raise money to send its president to Washington, DC for the suffrage demonstration Alice Paul was planning on March 3, 1913, to coincide with Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. Ida Wells-Barnett was one of more than sixty Illinois suffragists who made the trip — so many that the Chicago Tribune sent a reporter and photographer to cover the story.

Once the Illinois