Authors:

Historic Era: Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

July/August 2020 | Volume 65, Issue 4

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

July/August 2020 | Volume 65, Issue 4

Editor’s Note: We asked historian Paul Dickson to give us some perspective on the recent demonstrations in the nation’s capital. He pointed to the effort by thousands of veterans to get help during the Depression — protests that were met with violence, but eventually led to profound changes. Mr. Dickson coauthored The Bonus Army: An American Epic with Thomas B. Allen, and is the author of over 60 other books.

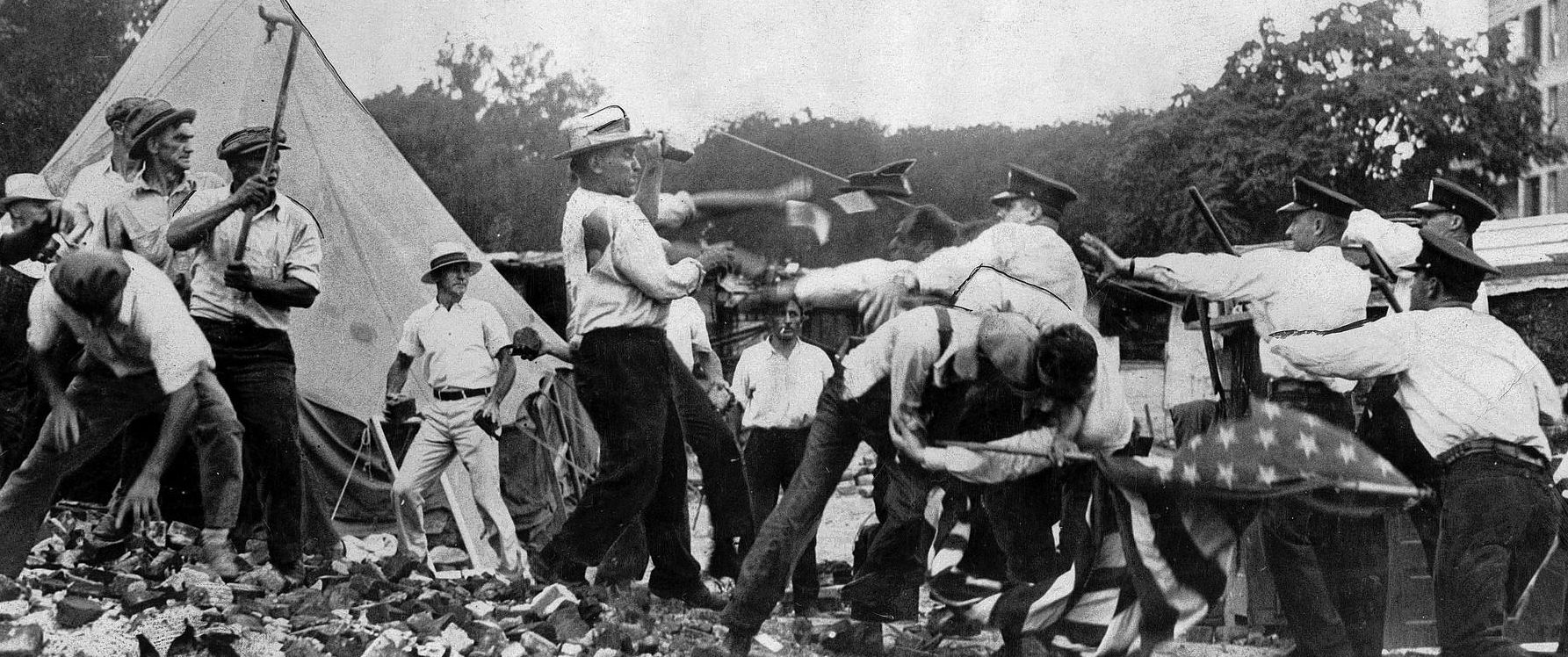

President Donald Trump’s threat to bring 10,000 Federal troops to the Capital to enforce the law after recent demonstrations is hardly the first time that the U.S. Army has been called upon to move against civilians. In 1932, an estimated 17,000 veterans and their families headed to Washington from across the country to protest and were set upon by cavalry, infantry, tanks and machine guns.

The marchers demanded payment of the “bonus” promised in 1924 to soldiers who had served in the Great War, but deferred until 1945 because of wrangling over the federal budget. Now, deep in the Depression, the vets had dubbed the delayed payment the Tombstone Bonus, for the only way to get the cash before 1945 was to die, in which case the payment would be made to the next of kin as a death benefit.

Victorious war veterans have vexed politicians since the days of Caesar’s legions. Returning warriors were both a potential power bloc and a threat — men who marched off to serve the state in war and then