Authors:

Historic Era: Era 10: Contemporary United States (1968 to the present)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

September 2020 | Volume 65, Issue 5

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 10: Contemporary United States (1968 to the present)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

September 2020 | Volume 65, Issue 5

The numbers are already grim. Worldwide, over 27 million have contracted Covid-19; nearly 875,000 have died from it. Public health experts caution that those numbers are certainly undercounts. Some deaths are mistakenly attributed to underlying conditions, not Covid-19, and many people who likely had the virus were not able to get tested. At-home deaths are often excluded. Overwhelmed health care systems lack the resources to generate reliable statistics.

As the spread continues, with the risk of second or third waves of infection, we should recognize that this pandemic – like those of the past – will change history. We should plan to embrace those changes that will improve our world, not worsen it.

When Athens battled its neighbors in the fifth century B.C., plagues repeatedly crippled the Greek city-state’s war effort, which ended in calamitous defeat. Nearly a millennium later, the “Plague of Justinian” cost the Byzantine Roman Empire its provinces in Italy and North Africa.

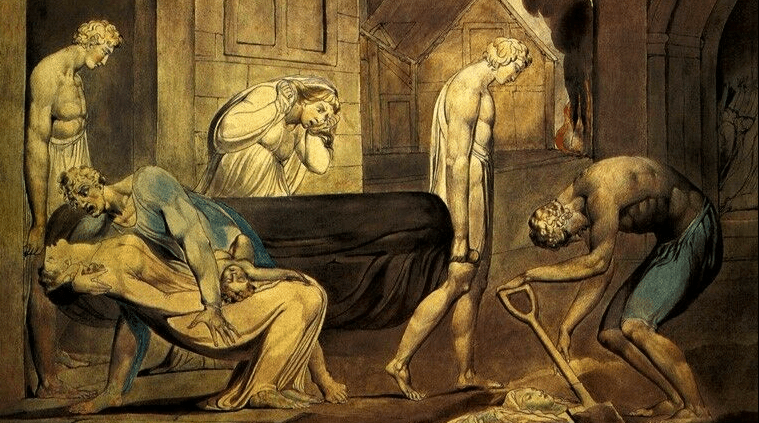

In the 14th century, the Black Death of Europe fomented massive popular upheavals. Terrified mobs annihilated hundreds of Jewish communities, a genocidal pattern that recurred with succeeding pandemics.

Charles Mann has pointed out that perhaps nine-tenths of the indigenous population of the Americas died from European pathogens in less than a generation, and that “arguably, this is the single most powerful explanatory fact in the entire history of the Americas post-1492.”

Popular violence followed cholera outbreaks in the United States in 1831-32, and plague in India between 1896 and 1900.

Recently, some television pundits have claimed that facing a pandemic is new for Americans and we haven't had to deal before with over-crowded hospitals or “social distancing,” even though those who read history know that was exactly what happened for epidemics of yellow fever, malaria, typhoid fever, cholera, or influenza.

Read about U.S. pandemics in American Heritage

The most studied pandemic is the devastating Spanish Influenza of a century ago, at the end of World War I, which killed some 40 million. German generals blamed the disease for the failure of their last-ditch offensive in July 1918.

The flu also changed the resulting peace conference when American President Woodrow Wilson suffered a health setback which his physician attributed to influenza. The weakened Wilson offered little opposition to schemes, which he had previously criticized, to give control of the Middle East to Britain and France and to grant the Shantung Peninsula of China to Japan. They would have lasting consequences.

Economists have tried to gauge the Spanish flu’s reduction of wealth globally, while demographers have concluded that babies conceived during that pandemic later experienced