Authors:

Historic Era: Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

July/August 2020 | Volume 65, Issue 4

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

July/August 2020 | Volume 65, Issue 4

An unlikely band of American librarians and archivists mobilized during World War II in a forgotten war effort centered on books and documents. Helped by an odd assortment of scholars, spies, and soldiers, the information hunters gathered enemy publications in the spy-ridden cities of Stockholm and Lisbon, searched for records in liberated Paris and the rubble of Berlin, seized Nazi works from bookstores and schools, and unearthed millions of books hidden in German caves and mineshafts.

Improvising library techniques in wartime conditions, they contributed to Allied intelligence, safeguarded endangered collections, and restituted looted books — and built up the international holdings of leading American libraries for the postwar period. These men — and a few women — came together in a series of enormous collecting missions that originated in the unique conditions of World War II.

The information hunters offer a contrast to the Monuments Men, the well-known army unit of curators and museum specialists who saved endangered art and culture in wartime. More than in any previous American war, World War II required the mobilization of knowledge to fight the enemy, and books and documents drew the attention of many different decision-makers and personnel, civilian and military. Foreign publications were seen as a potent source of intelligence; only over time did questions of preserving libraries, restituting looted collections, and building American libraries emerge.

At the outset of the war, no one could have foreseen the large-scale government-led operations to acquire, exploit, rescue, and restitute books. It turned out that the expertise of librarians and scholars aligned closely with American military and political objectives. Although they were on the margins of battlefields, the experiences of these information hunters shed new light on the war and its impact on American life.

On the eve of World War II, the American government had only limited capacity for foreign intelligence gathering. The FBI compiled dossiers on domestic threats and intercepted mail, American embassies reported on foreign developments, and the armed services began to strengthen military intelligence. But the U.S. was far behind Great Britain and Germany. As the international crisis mounted, President Franklin Roosevelt came to believe the government needed a robust intelligence capability.

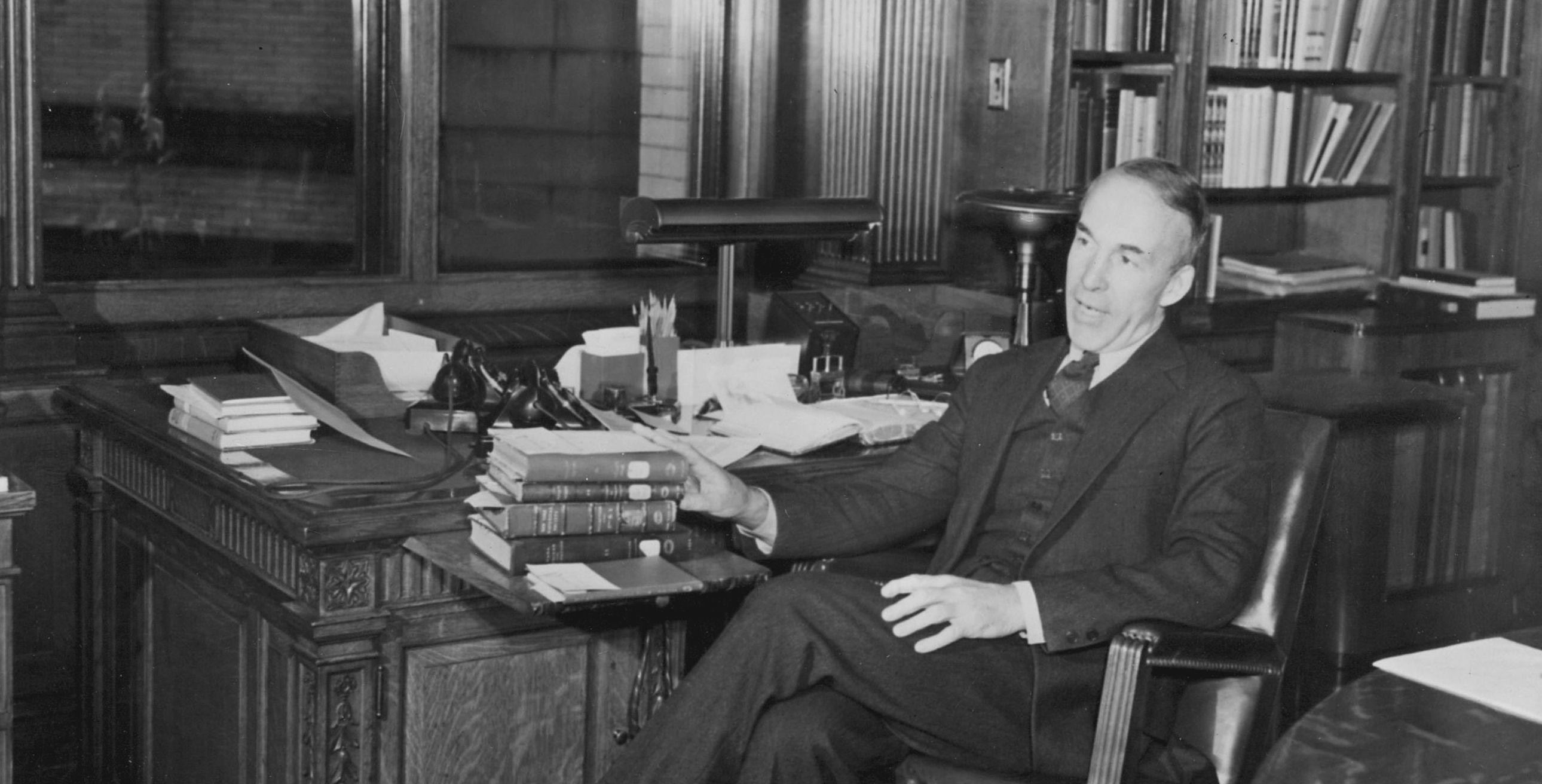

In July 1941, Roosevelt directed William “Wild Bill” Donovan, a decorated WWI veteran, lawyer, and politico, to build a civilian intelligence agency, which became known as the Office of Strategic Services or OSS. Initially the agency was called the Coordinator of Information, a significant name, for it was this new attention to information that led to the wartime collecting missions. It focused on the prosaic task of gathering and analyzing non-secret publications and documents.

Donovan enlisted the aid of Archibald MacLeish, the famed poet, playwright, and the Librarian of Congress. Under MacLeish, the Library of Congress had become the site of a new cultural-governmental alliance. An ardent interventionist, MacLeish urgently raised the stakes for librarians, calling on them to be not only custodians of culture but defenders of freedom.

Strangely enough, the origins of America’s vast intelligence apparatus might be traced to the meetings of these two men in the summer of 1941. Although Donovan would embrace espionage and secret operations, he initially turned to publicly available information to understand the enemy. MacLeish encouraged analyzing such sources using the methods and tools of scholarship, and he committed the Library to assist this effort. Foreign newspapers, scientific periodicals, industrial directories, and similar publications were in great demand. With the international book trade shut down by war, other means of acquisition had to be found. Not long after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt created an agency for this purpose called the Interdepartmental Committee for the Acquisition of Foreign Publications (IDC).

The IDC got off to a slow start, failing to acquire a single item in its first four months. Finally in April 1942, it began to send librarians and scholars abroad to collect and microfilm these materials. Initially the committee thought it could get by with a couple of agents, but the program expanded quickly, with personnel placed in London, Stockholm, Lisbon, Istanbul, Cairo, New Delhi, and Chongqing.

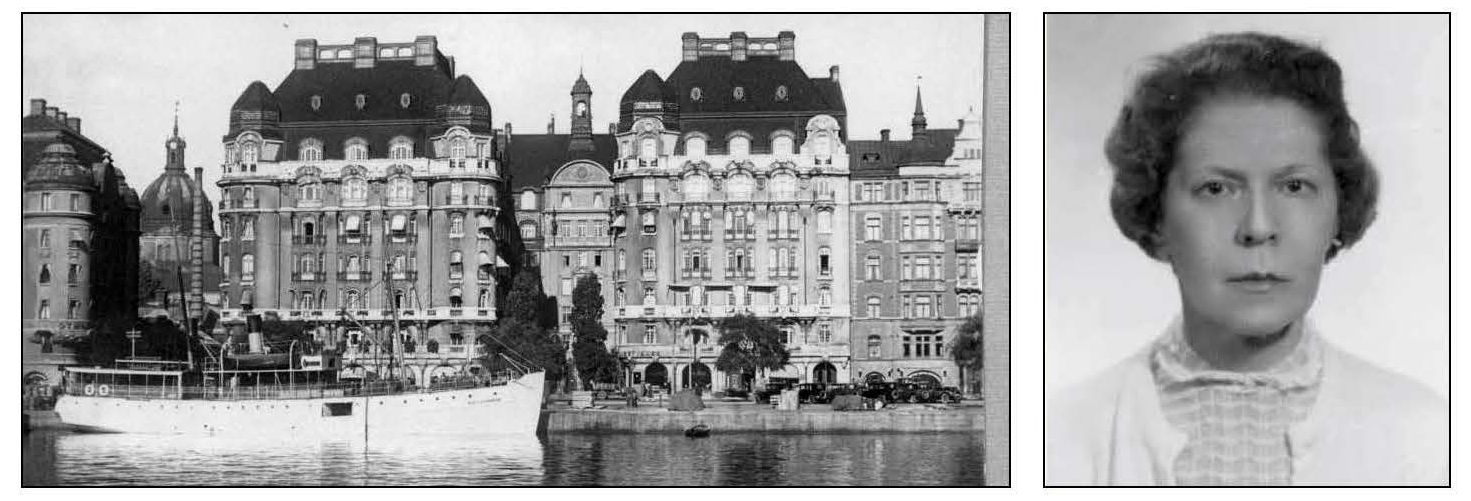

Heading the Stockholm operation was Adele Kibre, the only woman to serve as an agent in the field. She grew up in Hollywood, in a family connected to the film industry, but she had a scholarly bent and went to the University of Chicago to earn a PhD in medieval linguistics. Like many