Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Spring 2020 | Volume 65, Issue 2

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Spring 2020 | Volume 65, Issue 2

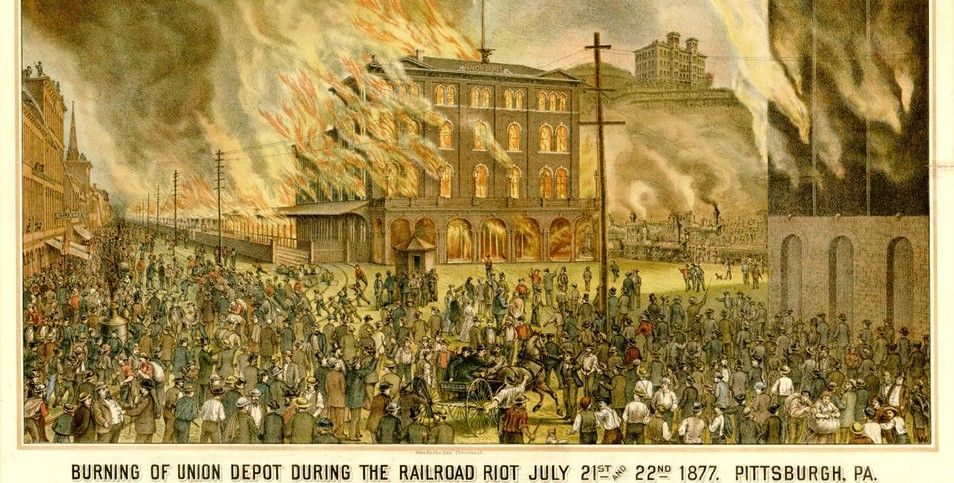

To the New York Tribune it was “an insurrection”; the St. Louis Republican called it “a labor revolution”; and the Pittsburgh Leader told its readers, “This may be the beginning of a great civil war in this country, between labor and capital.” The extraordinary events of July, 1877, did not quite add up to all that, but they certainly looked like a war while they were going on.

The Great Railroad War — or the Great Strike, as it came to be called when things had calmed down — was America’s first national labor uprising. It burst upon a hundred cities and towns and railroad crossings from New York to California: only New England and the Deep South were spared. Before it ended, more than a hundred persons had been killed and hundreds more injured; fully two thirds of the nation’s seventy-five thousand miles of railroad track had been affected; untold millions of dollars worth of railroad property had been burned, blown up, or torn apart. And, for the first time in U.S. history, federal troops in large numbers had been called out to crush civilian strikers.

Eighteen seventy-seven marked the fourth and worst year of the depression that followed the crash of ’73. Perhaps a million of the nation’s 4,500,000 non-farm workers were out of work. Trade unionism had virtually collapsed. Jobless men and their families choked city slums; thousands more roamed the countryside as tramps.

The railroads had sought to ride out the economic storm by cutting costs — including wages. The average trainman’s salary had already been reduced by 35 per cent since 1873. The men took it. They had little choice since there were no effective unions to fight for them and the countryside was full of unemployed men ready to take any job.

Then, four major railroads — the Pennsylvania, Erie, New York Central, and Baltimore & Ohio — announced a further wage cut of 10 per cent. With it came other economies that worsened the railroad man’s lot. Some lines began charging rent on the tiny track-side patches on which the trainmen’s shanties and kitchen gardens stood, and required crews to pay for return trips aboard trains they had just worked. (In one celebrated instance, a Lake Shore Line engineer was paid sixteen cents for operating one run, then charged a quarter to ride back home again.) And the railroads did all this to their men—and more—while continuing to pay out handsome dividends of 8 and 10 per cent to their investors.

It all finally became too much for the men to take, and on the hot morning of July 16 — the