Authors:

Historic Era: Era 7: The Emergence of Modern America (1890-1930)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Spring 2020 | Volume 65, Issue 2

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 7: The Emergence of Modern America (1890-1930)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Spring 2020 | Volume 65, Issue 2

Editor's Note: John Barry is the author of The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History, from which this essay is adapted.

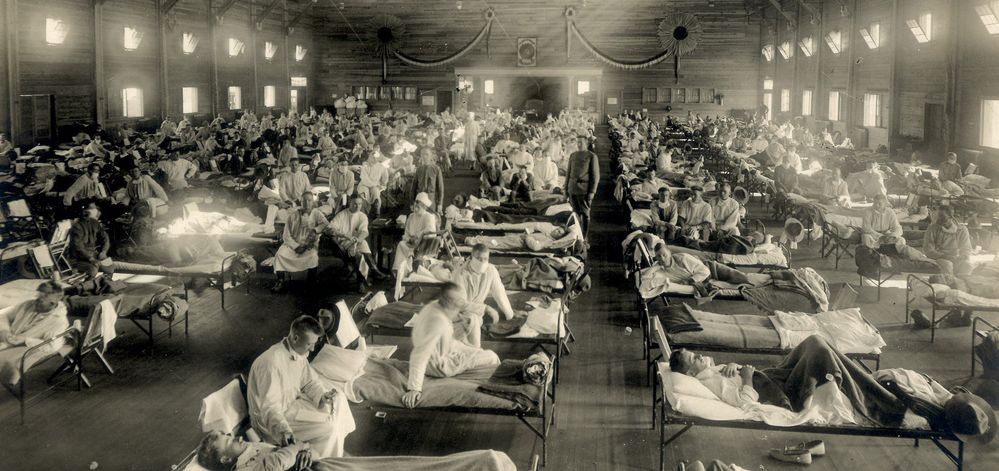

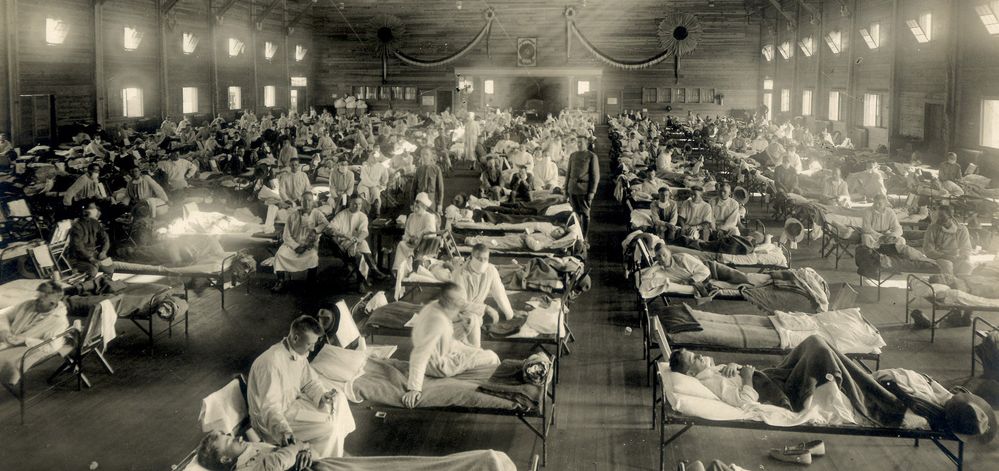

In August 1918, an influenza virus emerged — probably in the United States — and began to spread. When a young Navy doctor, Lt. John J. Keegan, saw how fast the disease moved through patients at the Chelsea Naval Hospital, he fired off a warning that it “promises to spread rapidly across the entire country, attacking between 30 and 40 percent of the population” to the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Keegan’s words proved prophetic. All over the world, the virus was adapting to humans, achieving maximum efficiency and turning lethal. Within each city, within each factory, within each family, into each store and each farm, along the length of the track of the railroads, along the rivers and roads, deep into the bowels of mines and high along the ridges of the mountains, the virus would find its way. In the next weeks, the virus would test society as a whole and each element within it. Society would have to gather itself to meet this test, or collapse.

Before that worldwide pandemic faded away in 1920, it would kill more people than any other outbreak of disease in human history. Plague in the 1300s killed a far larger proportion of the population — more than one-quarter of Europe — but in raw numbers influenza killed more than plague then, more than AIDS today..

The lowest estimate of the pandemic's worldwide death toll is twenty-one million, in a world with a population less than one-third of today's. That estimate comes from a contemporary study of the disease and newspapers have often cited it since, but it is almost certainly wrong. Epidemiologists today estimate that influenza likely caused at least fifty million deaths worldwide, and possibly as many as one hundred million.

Yet even that number understates the horror of the disease, a horror contained in other data. Normally influenza chiefly kills the elderly and infants, but in the 1918 pandemic roughly half of those who died were young men and women in the prime of their life, in their twenties and thirties. Harvey Cushing, then a brilliant young surgeon who would go on to great fame — and who himself fell desperately ill with influenza and never fully recovered from what was likely a complication — would call these victims "doubly dead