Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2020 | Volume 64, Issue 1

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2020 | Volume 64, Issue 1

Clouds of doom shrouded the nation in 1800. George Washington was dead.

For the first time in their 25-year struggle to govern themselves, Americans faced a future without the father of their country to lead them. And they lost their way.

Absent their commander-in-chief, the men who had helped him lead the nation to independence went mad. Chaos engulfed the land as surviving Founding Fathers Adams, Burr, Hamilton, Jefferson, Monroe, and others turned on each other as they clawed at Washington’s fallen mantle.

In a drama not unlike a classical Greek or Shakespearean tragedy, arrogance and lust for power gripped the souls of national heroes, perverting their patriotism, spurring them to spring on each other, fangs bared, spitting venom. Defying the Declaration of Independence and Constitution they had written and sworn to uphold, they ignored the commandments their religions demanded they obey. Madness swept them into its arms, with congressmen wrestling each other to the floor of the House, pummeling each other. Former battlefield comrades and close friends challenged each other to deadly duels, and high government officials plotted to disgrace, imprison, or murder those they perceived as political foes.

Presidents were not immune from the madness. John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, both signers of the Declaration of Independence, blatantly violated their oaths of office, stripping the Bill of Rights from the Constitution and, in Jefferson’s case, urging states to consider secession. The madness affected heroes as well. Virginia Senator James Monroe, a hero at the Battle of Trenton, plotted to disgrace Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton, who had helped save Monroe’s life at Trenton. Hamilton, in turn, plotted to disgrace Aaron Burr Jr., who had also fought at Trenton and rode with both Monroe and Hamilton at Monmouth Courthouse. In the postwar struggle for power, Hamilton’s scheming unseated President Adams in the 1800 presidential election and provoked the most dangerous constitutional conflict in early American history. Later, Hamilton’s insane feuding with Burr — by then vice president of the United States — ended in a disastrous duel that sent him to his grave and Burr to exile in Europe.

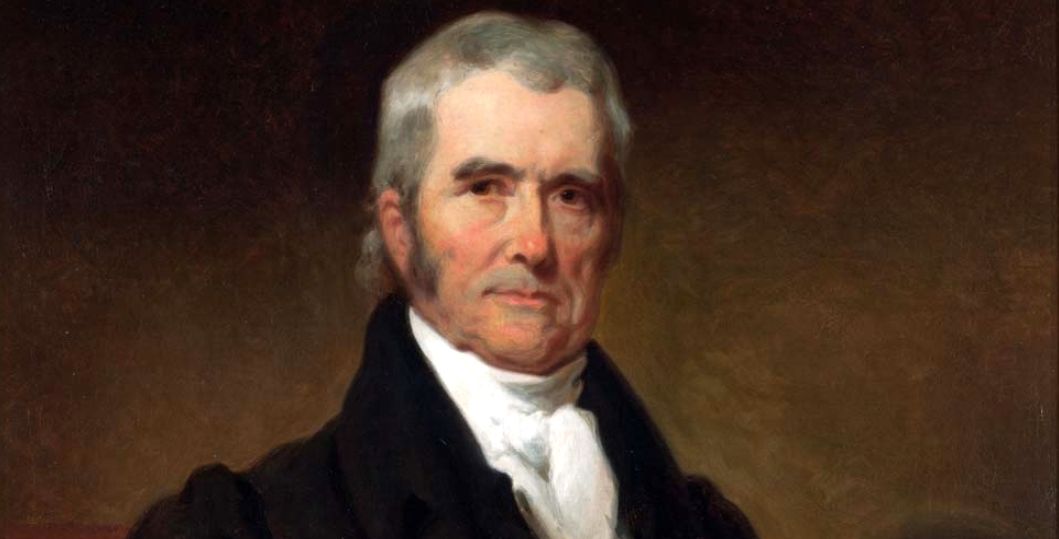

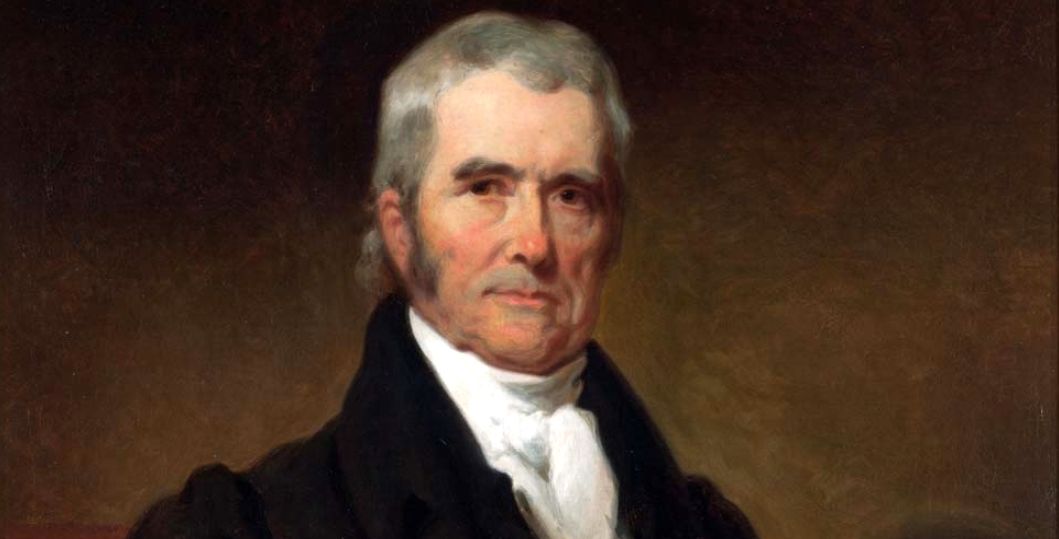

As scandal and ignominy tarred his former wartime comrades, one man stood apart from the chaos engulfing the government as heroic in peace as he had been in war. Like Burr, Hamilton, and Monroe, John Marshall had charged into enemy lines in New York, Trenton, and Monmouth and shared their suffering through the bitter winter at Valley Forge. Content to practice law at home in Richmond, Virginia, after the war he won national acclaim as a delegate in 1788 to Virginia’s ratification convention.

In one of the most dramatic debates in American history, Marshall challenged America’s legendary patriot Patrick Henry and argued for ratification of the Constitution — a document