Authors:

Historic Era: Era 9: Postwar United States (1945 to early 1970s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2020 | Volume 64, Issue 1

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 9: Postwar United States (1945 to early 1970s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2020 | Volume 64, Issue 1

A bully was stalking the Nation’s Capital. Insulting people, ruining reputations, using fear to bend Congress to his will. Behind the scenes, many said someone should stand up for American values. Someone from the bully’s own party should speak to the American people.

Margaret Chase Smith had served just a year in the Senate, yet many in Washington considered her a likely vice-presidential candidate on the GOP ticket in 1952. “The American people are sick and tired of seeing innocent people smeared,” Mrs. Smith told her fellow Senators. But “in those days,” she recalled, “freshmen senators were to be seen and not heard, like good children.”

When Joseph McCarthy produced a list of 205 Communists in government, Smith trusted him. “It looked as though Joe was onto something disturbing and frightening,” she said. But then she studied the documents McCarthy offered as evidence. She saw no evidence.

At first, she wavered. “I am not a lawyer,” she thought. “After all, Joe was a lawyer and any lawyer Senator will tell you that lawyer Senators are superior to non-lawyer Senators.” Surely, she hoped, “one of the Democrats would take the Senate floor.” But when no challenge came, “it became evident that Joe had the Senate paralyzed with fear.”

Back in Skowhegan, Maine, folks knew Maggie Chase. Her father was a barber; her mother worked in shoe factories. Maggie went straight from high school into teaching, then journalism. Only when she married her publisher, Clyde Smith, did she enter politics, accompanying Mr. Smith to Washington when he was elected to Congress during the New Deal. When he died four years later, she won a special election, then won four elections on her own, racking up 60-70 percent of the vote.

Though beloved in Maine, in Congress Smith was known more for her attire than her expertise. Nattily dressed, she always wore a red rose in her lapel. And that was all Congress expected from the junior senator from Maine. But then she gave Congress a lesson in integrity.

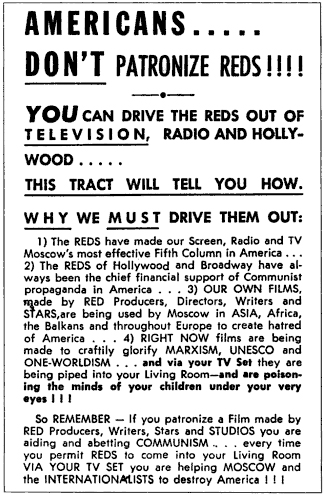

As McCarthy grilled one accused communist after another, Smith began to speak out. The American people, she wrote in her nationally syndicated column, need “written evidence in black and white instead of conflicting oral outbursts in nebulous hues of red and pink.” But the grilling continued.

On June 1, 1950, as Smith boarded the Senate tram, McCarthy approached.

“Margaret,” he said, “you look very serious. Are you going to make a speech?”

Smith remained as unfluttered as the rose in her lapel. “Yes, and you will not like it.” When McCarthy