Authors:

Historic Era: Era 10: Contemporary United States (1968 to the present)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

September 1992 | Volume 43, Issue 5

Authors: Bernard A. Weisberger

Historic Era: Era 10: Contemporary United States (1968 to the present)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

September 1992 | Volume 43, Issue 5

Recently, I got a letter from a friend of mine, Max Lale, the current president of the Texas State Historical Society, that gave me a quick glimpse of a vanished world. Lale recalled that on election day of 1928, when he was twelve, he accompanied his father on a mile-and-a-quarter walk to their local polling place in Oklahoma. There he waited while his Southern-born father, faced with a choice between Al Smith and Herbert Hoover, agonized over which would be worse: to support a Catholic or a Republican. In the end he cast no vote for president. It was impossible to betray either the Protestant religion or the Democratic party.

Old-time Republican voters would have understood, even if they did not agree. To them, as the iconoclastic trial lawyer Clarence Darrow recalled of his childhood neighbors in Kinsman, Ohio, in the 1870s, “the Republican Party and all of its doctrines came as a divine revelation.”

That’s how seriously people took political affiliations a long time ago. It seems like a very long time ago in this election year. When, if recent trends hold up, the following predictions can safely be made. Only about half of those who are registered to vote will do so. A great many of them will split their tickets and cast ballots for a Republican president but a Democratic representative and, in some cases, senator. Of this active ticket-splitting electorate, many members—perhaps a majority—will define themselves as “independents.” And whatever the November outcome, virtuous media commentators will denounce both President and Congress for displaying election-year partisanship in their disagreements with each other, as if a partisan view were always automatically counter to the national interest.

Overtly playing politics— at least, old-style party politics—is currently a public relations felony. Among journalists and political scientists there is even an ongoing debate over whether or not the traditional American party system is still breathing. Some hold, as David Broder of the Washington Post did in a book published twenty years ago, that The Party’s Over. Others cleave to the beliefs of the political scientists Xandra Kayden and Eddie Mahe, Jr., who contended in a 1985 volume that the Party Goes On but in a new and modernized form that we don’t yet recognize. Whichever is closer to the truth, there is no denying that the Republican and Democratic national organizations have plummeted in popular esteem and loyalty.

That in itself says a good deal about how this nation has changed in this century, because the American political party was something special,

The key question, of course, is which, and it can’t be answered in a few thousand words, if at all. But a look at the life histories of our two major (and our array of minor) parties can help clarify the record. It may even help those who are deciding at this moment which candidates they will honor with what Mr. Dooley called their “invalyooable suffrage.”

The story begins with a somewhat startling fact. Parties are intruders into the constitutional scheme of things. Though they have almost always been at the core of American political life, they were neither welcomed nor provided for by the framers, who for the most part would have been sturdy supporters of the “nonpartisan” ideal if it had been articulated in 1787.

In a modern democracy, we see a political party simply as a permanent organization of persons bound by common interests who agree to support a particular set of candidates and principles at election time. But the suspicious Founding Fathers made little distinction between a party and a faction , dictionary-defined as “a small, cohesive and usually contentious group within a larger organization.” In the classical “republic of virtue,” which was their eighteenth-century ideal, contention would give way to a reasoned consensus on the general good, which wise voters and officeholders would pursue even if it seemed to conflict with their local and temporary self-interest. No leader worthy of the name would encourage group antagonisms that might tear apart the fabric of society.

The prize example of such a paragon was, of course, George Washington, whose unanimous and decidedly non-partisan choice as president by the electoral college in 1788 seemed to be an ideal illustration of how the system was supposed to work. It was. But it happened exactly once and never again afterward.

That may have disappointed the framers without surprising them. They were not self-deluded Utopians. They had plenty of experience with factions in their colonial assemblies, and they did expect that in a big and growing country a diversity of religious, social, and economic interests would soon make unanimity impossible. What they lacked was a clear picture of how such interests would organize themselves on a regular basis and contend for power. What they hoped was that no sinele one would become strong enough to dominate

The gladiators quickly arranged themselves around the two dominant personalities in Washington’s cabinet. Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton advocated a powerful central government that encouraged trade, banking, and manufactures and that openly favored its wealthiest citizens because their support would guarantee the nation’s permanence and stability. Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson thought distinctly otherwise. Only a decentralized republic built around communities of independent landowners would protect freedom from the raids of the greedy, the power-hungry, and the demagogues who served them. Soon the two men and their followers were at one another’s throats, much to the distress of Washington, who saw what was coming and warned that “the spirit of revenge natural to party dissension” had caused “the most horrid enormities” in the past.

Those who were of Hamilton’s mind took the name of Federalists, used by the supporters of the Constitution during the battle over its ratification. They were nation builders and numbered some of the most distinguished creators of America: Hamilton himself, President John Adams, Chief Justice John Marshall. They tended to put little faith in the people at large, whereas Jefferson’s every instinct, slaveholding elitist though he was, prompted him toward a steady widening of the scope of freedom. The debate was, in Alexis de Tocqueville’s words, “as old as the world itself,” between those who “wanted to restrict popular power” and those whose desire was “to extend it indefinitely.” Jefferson and his cohort accused the Federalists, with their love of tradition and authority, of leaning toward monarchy. To separate themselves clearly from that heresy, they used the name of “Republican.” In time, some became unabashedly willing to take the label of “Democratic-Republicans.”

The reader will immediately recognize that the names of both of today’s major parties are derived from that Jeffersonian coalition. Did Hamilton’s ideas die without progeny, then? Not by any means, but be patient. There is a winding path to travel yet.

The Federalists and the Republicans created a constitutional headache in 1796, when John Adams got the most electoral votes for president, and Jefferson, as the runner-up, automatically became his vice president. The two camps were still basically factions that did not look entirely unfamiliar to those who knew English politics, then dominated by two parties—landowning, conservative “Tories” and business-oriented, modernizing “Whigs.” The labels, however, basically described small groups of parliamentary leaders whom a smart king could play off against one another in the kind of game Dickens later satirized in Bleak House, with

American politics quickly broke away from that pattern. Though the electorate here was still mainly restricted to property holders inclined to defer to the wisdom of gentlemen, it was nonetheless much larger than England’s, and far more widely dispersed. It took a great deal of organizing, committee forming, and letter writing to unite the scattered political clubs into a cohesive party. The wonder is how effectively it was done at the speed of post riders on miserable roads. Even so, the nature of American geography and society required that a good deal of leeway be left in local hands. So while British parties were tightly knit and run from the top down, American parties were aggregates of independently created local and state organizations, each with a voice of its own.

As a result, general statements about American parties must be nibbled at cautiously rather than swallowed whole. It might be safe to say that the Federalists stood in a broad way for social conservatism, a strong central government, and trickle-down economics, and the Republicans for the opposite. But Federalist and Republican candidates for a governorship in some state might slug it out over purely parochial issues, unhitched to overarching political doctrines. And, even at the congressional level, party members jumped fences when some compelling interest in their district so dictated.

Nonetheless, the violence with which the Republicans and Federalists went at each other during John Adams’s administration seemed to justify Washington’s fear of “horrid enormities.” The wars of the French Revolution furnished a fiery background against which the pro-British Federalists and pro-French Republicans denounced each other as Jacobins, Tories, atheists, and inquisitors. The repressive Alien and Sedition Acts, passed in 1798 by the Federalist Congress, looked like an ominous warning of bloody strife to come.

But then came Jefferson’s election, labeled by some historians “the revolution of 1800.” In his inaugural address the philosopher of revolution called for conciliation. “We are all Republicans,” he said, “—we are all Federalists.” Every difference of opinion did not have to be a difference of principle. There were no reprisals, other than the replacement of Federalist job-holders, no arrests, nothing except a convincing demonstration that power could peacefully pass from one party to the other when the voters spoke. It was the clinching demonstration that the constitutional system—political parties and all—was working and would endure.

So it would, but not without change. Inside of another twenty years, the initial party system got a vigorous shaking up. The Federalists died, and the Republicans were transformed and renamed, all because of two irresistible and linked forces: national expansion and the rise of democracy. The curtain went up on the second act for American parties. This one saw the birth

The Republicans not only won in 1800 but took the next five presidential elections in a row, conferring double terms on Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe—the so-called Virginia Dynasty. Beaten time and again, the Federalists remained strong for a while in New England but gradually sank out of sight. This was not because their economic concepts were rejected but because their open courtship of privilege ran counter to the incoming tide of democracy and especially because their pro-British leanings put them on the wrong side of patriotic public opinion during the War of 1812, which most of them opposed. (Diehards from Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island held an antiwar convention at Hartford in December of 1814 and succeeded only in making themselves vulnerable to campaign charges of treason.)

It was ironic that the nationalistically minded Federalists should make a last stand defending the rights of states not to cooperate fully in “Mr. Madison’s war,” but that was to be expected when they were constantly shut out of control of the central government. They were no more inconsistent than the Republican administrations that doubled the size of the nation by purchasing Louisiana and Florida and that took the country into a costly conflict to defend freedom of international trade. These switches simply illustrate a second rule about American parties. Not only do the national organizations fail to impose ideological consistency on their state counterparts, but their own positions on the proper constitutional powers of the state governments, the Congress, the Presidency, and the Supreme Court often shift around, depending upon who is temporarily entrenched in any of those institutions. This is not to say cynically that all party principles are disposable, but merely that the flip-flopping reflects the federal system in operation and the intensely pragmatic nature of American political life.

At any rate, the Federalists were out of the national picture after 1816, and for practical election purposes American voters were all Republicans. But this so-called single-party (or no-party) “era of good feelings” was deceptive and did not last long. True, there was an invigorating flush of almost universal pride in the country’s successful emergence from the war, in the rush of westward expansion, and in the surge of industry and invention. Everyone was, in the modern sense, “pro-growth.” But unsettled questions remained. What kind of banking system should provide the credit for investment in canals, steamboats, turnpikes (and, later, railroads and telegraph systems)? Should the federal government and the Treasury have a hand in encouraging a transportation network? What about a tariff to protect those new textile factories from foreign competition? And those millions of acres of land owned by the nation—should they be virtually given away to immigrant and native-born pioneers? Or kept as a good source of revenue, to be sold at a controlled pace to well-heeled developers and town founders?

Splits over these issues would soon fracture the old-time Republican monolith

Jackson actually had the highest number of electoral (and popular) votes, and in bypassing him, the House made the profound mistake of ignoring the hurricane of democracy that had blown Federalism away. Universal manhood suffrage was becoming a reality in almost every state as property and religious qualifications for the vote were toppled by popular outcry. Universal was anything but an exact term. It meant white males only. Even so, a huge and newly enfranchised body of voters stood ready to crush any kind of elite that seemed to put itself between them and success. Jackson the Indian-killer, the victor of New Orleans, the uneducated and unpolished frontier youth who had made himself a gentleman planter, a judge, and a senator was their symbolic and actual hero.

He played the role to the hilt and re-established party politics by the loyalties and hatreds he created. He ran again in 1828 and, this time, made it to the White House, where he spent eight years smashing and roaring, fighting the “monsters” of monopoly and privilege, freely using the veto, defying the Supreme Court and Congress when he chose, and establishing a whole new concept of the President as “the people’s” friend and the prime mover of the national government. When the time came for his reelection in 1832, his supporters were proud to call themselves Democrats. The modern Democratic party may honor the cerebral Jefferson as one of its founders, but the true paternity lies with the fiercely partisan Jackson. He made it a fighting electoral force.

Jackson’s opponents were an assorted lot of spokesmen for modified Hamiltonian economics. In a very loose way, they wanted more nationalized control over the growth process—a powerful central bank, tariffs, conservative administration of the public domain, federal support of the “internal improvements” that would build a nationwide market (rather than an uneven patchwork of state and local investments). They had trouble coordinating their policies, but they were united in seeing Jackson as a dangerous demagogue. They called themselves National Republicans at first, but by the end of Jackson’s second term, they had found the catchier label of Whigs. English Whigs had fought against the power grabs of the king, and they, the American Whigs, would defend liberty against “King Andrew.”

And so from 1836 to 1852, after a long lapse, two-party politics was reborn as the Whigs battled the Democrats. The Whigs’ national

Though they sounded somewhat like reincarnated Federalists, the Whigs did not—could not—make the mistake of ignoring the common voter. Even American conservatives could no longer win without wooing the humble citizen in his own language. The Whigs did just that in 1840, when they out-demagogued the Democrats by running General Harrison, “Old Tippecanoe,” as a homespun soldier content to live in a log cabin and drink hard cider. He was actually a scion of Virginia’s plantation aristocracy, but no matter, the strategy worked, and in both parties the warmth of victory melted away any intellectual qualms.

In fact, universal suffrage was changing the basic machinery of politics. Both parties now organized vigorously at the grass roots. Meetings were held in townships, counties, and congressional districts to adopt resolutions, nominate local officials, and choose delegates to statewide or regional gatherings that in turn endorsed national candidates. In 1831, a short-lived third party known as the Anti-Masons came up with the idea of a national convention—held in Baltimore—to write a platform and pick a presidential standard-bearer. Both platform and candidate, William Wirt, are long forgotten, but the idea was quickly taken up by the other parties. The three- or four-day orgy of raucous speechmaking, celebrating, and factional infighting became a fixture. “If it were an agreeable subject,” William H. Seward wrote to a friend regarding that prototype gathering, “I would describe to you all the hustle, excitement, collision, irritation, enunciation, suspicion, confusion, obstinacy, fool-hardiness and humor of a convention.” None of those ingredients were lacking in the ones that followed.

The new order of things raised the status of a new kind of professional, the party worker who could organize masses of men and guarantee their “correct” vote. Likewise of the candidate who could deliver a stump speech more rousing than reasoned. Political rallies became, like the revivals and camp meetings they resembled, a form of public theater, alive and clangorous, torchlit and ritualistic, parading to the beat of campaign songs under fluttering banners emblazoned with slogans and portraits. Between elections, enthusiasm was sustained by party-subsidized newspapers that scorned the pretense of objectivity. Attacks on the personal and moral

The system engrossed the attention of those allowed to share in it. Some 2.5 million votes were cast in 1840 by a population of adult white males that probably did not number more than 3 million altogether. Dickens, on a visit the following year, complained of Americans’ “eternal prosy conversation about dollars and politics (the only two subjects they ever converse about).”

Most of what Dickens heard would have come from the dominant Whigs and Democrats. Third parties, then as now, were temporary shelters for voters with short-term unaddressed grievances, drawn together by some single idea, such as the Anti-Masonic party’s objection to “aristocratic” secret societies. When third parties showed strength, the major parties incorporated some of their ideas, then surrounded and ingested them, as the Whigs did with the Anti-Masons.

Both Whigs and Democrats needed votes in each of the different major sections that then made up the nation: the plantation South that imported heavily, the capital-hungry West, and the industrializing Northeast. The parties’ platforms were usually packages containing a balanced mixture of economic proposals with something for every point of the compass. Between such engineered compromises and the party organizations that reached from the White House down to county courthouses, the Whigs and Democrats were among the strongest of the bonds tying the United States together.

But, in the 1840s, the ties began to snap. The parties could not successfully make internal compromises on the uncompromisable, slavery. Relentlessly the question gutted and polarized both of them. The Whigs felt the strain first. Some of their stroneest bases were in New England and New England’s cultural extensions in those states bordering the Great Lakes, where abolitionism was swiftly ripening. The Democrats, on the other hand, were more strongly rooted in the South and Southwest, far less fertile ground for anti-slavery sentiment. Because of a Democratic convention rule—not repealed until 1936—that required a two-thirds vote to nominate a president, Southerners had enough strength to suppress the issue for a longer time.

But not forever. The abolitionist Liberty party, founded in 1840, pulled only 7,000 votes that year, but its total leaped to 62,000 in 1844. In 1848, “conscience” Whigs and antislavery Democrats joined in a Free-Soil party that was willing to stand for a half-loaf settlement of the question. Free-Soilers would leave slavery untouched where it existed but would bar it from all existing and future territories not yet organized into states. The effect would be immediate, since the Mexican War had just added the territories of California and New Mexico and, in fact, the whole present-day Southwest to the map. The Free-Soil ticket was a blue-ribbon alliance, former Democratic President Martin Van Buren at its head, and Charles Francis

The Free-Soilers met a happier destiny in 1854, but under another name. That year Southern Democrats in Congress, as the price for voting to organize the territories of Kansas and Nebraska, insisted on opening them to slavery and thereby repealing the thirty-four-year-old Missouri Compromise. Across the North outraged coalitions of “anti-Nebraska” Democrats, Free-Soilers, and conscience Whigs held mass meetings to denounce the plot of the “Slave Power” to deliver the entire West to the peculiar institution. Out of these inflamed gatherings rose a new organization, the Republican party reincarnated. Presumably, the name came from independent Democrats claiming to be the true heirs of Jefferson, whose humane, liberal ideals had been betrayed by the proslavery zealots who now dominated the Democrats. But the name did not change the fact that the new Republicans were and remained basically Hamiltonian and Whiggish in economic thought. Their primary identification at birth, however, was bedrock opposition to the further extension of slavery. They argued that if confined, slavery would gradually and justifiably die and so end the problem without strife.

The Republicans broke all precedents for instant success. In 1856 their first presidential candidate, John C. Frémont, won 114 electoral votes, only 35 short of the needed majority, and they also elected 92 representatives and 20 senators. From the start they were the second major party. The Whigs were gone, and the only other challenge in 1856 came from the American, or Know-Nothing, party, which got Maryland’s 8 electoral votes. This, too, was a one idea third party, a transient holding pen for those cut adrift by party shakeups. Its one idea was hostility to foreigners and Catholics. It had a brief run of success in industrial Massachusetts before its quick demise; its 1856 attraction for many conflicted borderstate voters was that it took no clear position on slavery.

The Democrats at last split in their final pre-Civil War convention in 1860. Northern Democrats who had not already defected to the Republicans nominated Stephen A. Douglas, the leading spokesman ffa for a morally neutral “deal” on slavery in the territories—namely, leaving it up to the Vf6 actual settlers to decide prior to admission to statehood. It was not enough for extreme pro-slavery Democrats, who by then were demanding federal protection for slavery wherever the flag went. They walked out and named their own candidate, John C. Breckenridge. A fourth party was formed, mainly by

Abraham Lincoln won, with a clear electoral-college majority and without the vote of a single Southern state. Southern hotheads seized on that as “proof” that the South and its institutions were no longer safe within the Union. Secession and war followed, and both the Union and the party system that had helped keep it together lay in ruins.

But only as a prelude to triumph. A stronger Union and a two-party system more vigorous than ever arose from the carnage. The third act began in 1865 and lasted until another war, almost eighty years later, rang down the curtain.

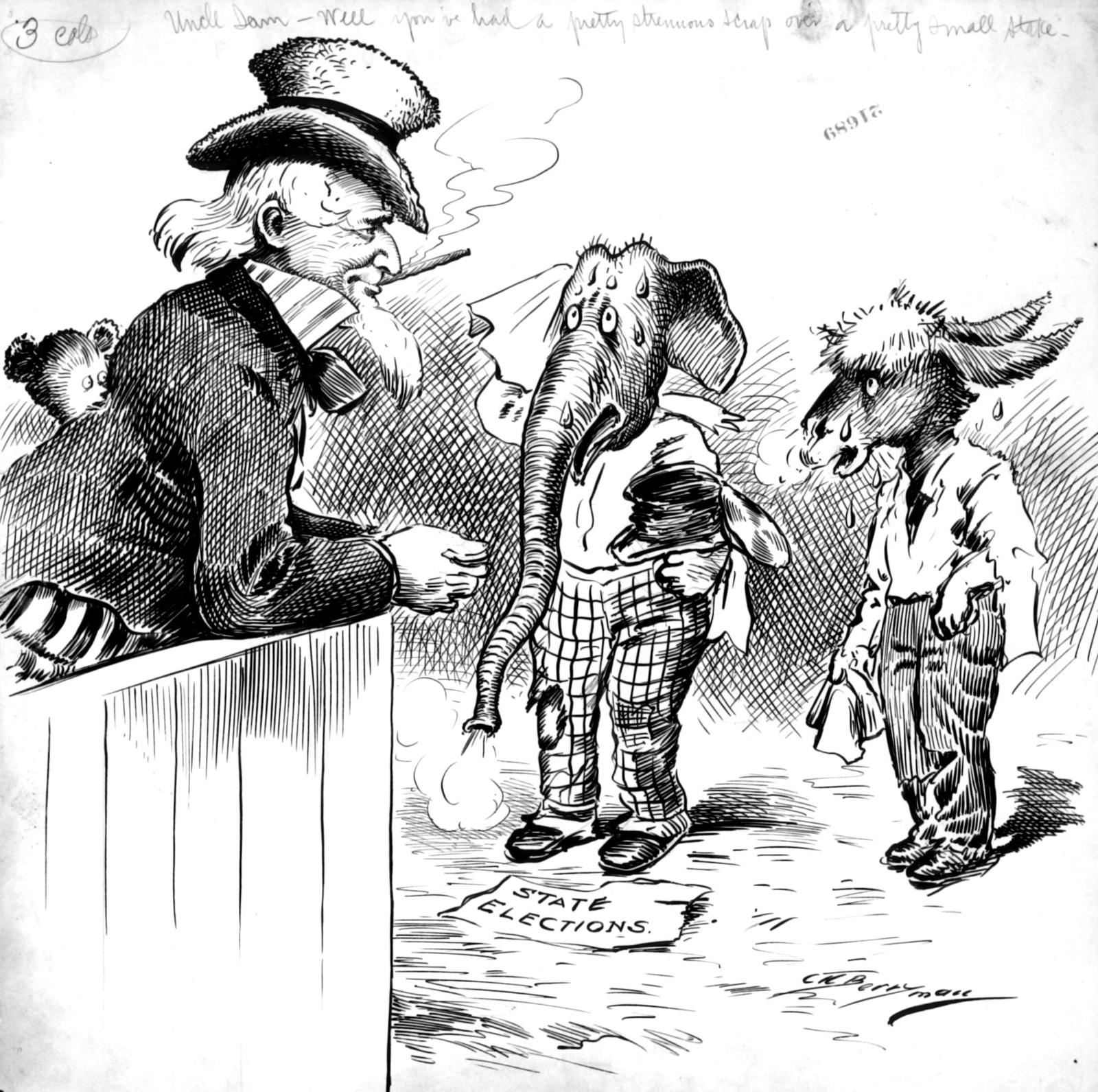

The agonies of battle, occupation, and Reconstruction set a fiery new brand of emotional partisanship on national politics. The elephant and donkey (invented by the cartoonist Thomas Nast at this time) became symbols as highly charged as the grand old flag or the old rugged cross. In the North the Republicans proclaimed themselves the party that had, in Robert M. La Follette’s words, “fought a desperate war for a great and righteous cause” and “had behind it the passionate enthusiasm of a whole generation.” It was, for young men like himself in the 188Os, “the party of partriotism.” Republican slogan makers put it tersely to veterans: “Vote as you shot.” Meanwhile, the Republicans’ Hamiltonian generosity to bankers, railroad builders, and manufacturers I encouraged the postwar I industrial boom and allowed Republicans likewise to identify themselves with growth and progress.

In the South, the war had directly the reverse result. During Reconstruction the states of the occupied South were run by Republican governments elected by freed blacks, newcomers from the North, and local white allies taking advantage of new political openings. For that reason, when pre-war Southern leaders regained control of the region’s politics and culture, after 1877, the very name of Republicanism was associated with whatever was hateful to them. No “decent” white man would any more vote Republican than he would defile the graves of his ancestors. The Solid South was born. Every Democratic presidential nominee began his campaign with a bonus of the South’s small but unwavering electoral vote. In Congress persistently re-elected Southern Democrats were able to translate their seniority into important leadership positions.

By the late 1880s, the two parties were in fairly even balance in voting for Congress, and control on Capitol Hill passed frequently from one side to the other. Since the Democratic leadership had by then signed on to approving industrial growth, there was no significant Democratic-versus-Republican debate on the overall drift of the nation away from its old anchorage in an agrarian majority. Critics of the new order fought their battles within the ranks of each party and generally lost.

But in 1892 came a change. Wheat and cotton farmers found themselves desperately squeezed between falling prices for the crops they sold and higher charges for the money they borrowed and the goods and services they bought. They blamed

The 1896 election turned out to be pivotal. Bryan was the last Jacksonian, a political liberal and a religious conservative who truly believed that the voice of the people was the voice of his fundamentalist God. He ran an impassioned speaking campaign built primarily on a single Populist proposal—namely, to spread wealth by permitting the unlimited coinage of plentiful silver at an artificially high fixed ratio to gold. The sixteen-year-old Vachel Lindsay remembered being thrilled at a Springfield, Illinois, rally by “Bryan, Bryan, Bryan/Candidate for President who sketched a silver Zion.”

The rest of the country was not so enchanted. Outside Bryan’s rural strongholds in the South and West, Republicans convincingly argued that a Bryan victory would ruin credit and commerce and k forever destroy the country’s manufacturing prosperity. Workers, as well as farmers dependent on urban markets, believed it. William McKinley won a huge victory, and Republicans totally dominated the federal government for the next decade and a half.

Two fresh landmark political truths had been established. One was that American voters now equated their fortunes and prospects with continued industrial health, and therefore job security became and almost always remained the dominant issue in their decision every four years on which party to entrust with the key to the White House. The other lasting truth was that the Republicans had repositioned themselves for a new generation, not as the Grand Old Party of Union and freedom but as the party most friendly to business.

But not without argument. Dealing with business, big and small, was at the top of the new twentieth-century agenda, and Republican “progressives” battled with “standpatters” to rein in irresponsible industrial leadership. It is easy to forget that Republicans like George Norris, Albert Beveridge, and Robert La Follette were among the first to campaign for regulating the railroads, clipping the wings of high finance, and rescuing the public domain from developers who grabbed with both hands. Other Republicans fought for laws to promote industrial health and safety, to protect the weak among workers, to make post-frontier democracy humane and fair. Theodore Roosevelt seized the spotlight as the prime example of a Republican progressive. As President from 1901 to 1909 he gave reform supervisibility, only to see conservatives seize the party helm again during the administration of his successor, William H. Taft. The old guard had—and would thereafter keep—the top hand in the GOP. When TR tried to win the nomination for another term in 1912, their

The Democrats meanwhile had their own intraparty battles. There were the Bryanites, there was a cadre of conservative Democratic lawyers and bankers who sometimes got to name the candidate (like Alton B. Parker in 1904), and there were the leaders, often Irish, of the urban Democratic machines that flourished among the huddled masses of new immigrants. The three groups battled so relentlessly that Will Rogers later liked to remark: “I belong to no organized party. I’m a Democrat.”

The machine, refined by constant testing and experience, was the greatest artifact of the golden era of American two-party politics, a mighty Americanizing and urbanizing force. At the neighborhood level it relied on an army of workers who garnered loyalty by helping the otherwise helpless to find jobs, get emergency food and fuel, and cope with landlords, courts, and licensing bureaus. On this foundation of free coal and turkeys and attendance at weddings, wakes, bar mitzvahs, and balls (plus some outright fraud in the count when necessary), a deliverable vote was built for the organization’s nominees to become aldermen and assemblymen and judges. The machine boss then guaranteed that these officials would approve whatever legislation, franchises, tax abatements, and court decisions were desired by the corporations with which he did business. The whole operation was lubricated by graft. “I seen my opportunities and I took ’em,” said one Tammany officer, George Washington Plunkitt, of his part in the system. It provided at both ends—social service for the poor and the removal of impediments to growth for rich entrepreneurs—but at a whacking cost in money and fairness.

While machine politics were often associated with big cities and Dem- ocrats, Republican state (and some urban) machines worked in comparable ways, firmly slamming the door on outsiders with new ideas. For that reason they became the target of the political prong of the progressives’ attack on the ills of democracy. The system of privilege, they argued, could be broken only by opening the system to thoughtful citizen participation through such devices as direct primaries to replace power-brokered conventions, secret ballots to prevent intimidation, or the initiative and referendum to allow voters, by petition, to have a say on issues that got buried in boss-dominated legislatures. The progressives had abiding faith in the power of informed opinion. Enact the direct primary, La Follette argued as early as 1897, and “intelligent, wellconsidered judgment will be substituted for unthinking enthusiasm, the lamp of reason for the torchlight.”

This was an early warning that the post-1865 party system was getting past its prime. Although he was talking of party primaries, La Follette was actually exalting a modern version of the nonpartisan ideal that the Constitution’s fathers had found attractive. The civil service reform movement of the 188Os had revived it as

In short, progressive thought was split between a desire to improve the f responsiveness of the parties and a conflicting feeling that the way to better government might not be through parties at all but rather around them or without them. The contradiction lingers to this day, an essential part of an unresolved debate over how to get governmental expertise without losing popular control. When anery enough, the debaters denounce one another as elitists and demagogues.

But, to return to history, 1912 was a peak year for progressivism. Instead of a Bryanite, a city boss, or a Wall Streeter the Democrats nominated a progressive professor, Woodrow Wilson. Theodore Roosevelt’s followers organized an independent Progressive party to run “the Colonel.” Between them Roosevelt and the victorious Wilson got more than 10 million votes to Taft’s 3.5 million. There were even 900,000 for the Socialist Eugene V. Debs. It did appear as if the old party system was indeed tottering.

Obituaries would have been premature, however. World War I and the 1920s arrested the national progressive advance, and Republicans and Democrats did business very much as usual, with the standpat Republicans getting much the better of it as they successively elected Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover and kept congressional majorities. The Democrats ran another conservative lawyer (John W. Davis) against Coolidge in 1924. Nearly 5 million dismayed progressives in both parties thereupon voted for the independent candidacy of the now-aged La Follette, but he won only Wisconsin’s 13 electoral votes. His defeat confirmed anew the ironclad grip of the two-party system. Americans do not vote to express principles or make educational statements. They vote to win, and most of them were then and thereafter certain that third parties could not win. Thanks to this somewhat self-fulfilling prophecy, only a tiny percentage of popular ballots are ever cast for third- (and fourth-, fifth-, and sixth-) party presidential candidates. Excluding Theodore Roosevelt’s 1912 total, La Follette’s 16 percent was the high-water mark.

There was a quiver of change in 1928, when the Democrats nominated Al Smith, so proudly from the sidewalks of New York and so uncompromisingly Catholic that four states of the former Confederacy committed the heresy of going Republican. There was an off-setting factor in Smith’s capture of the twelve largest cities of the nation, a sign of impending upheaval, but not yet enough to win for the Democrats. It took the Great Crash to do that.

And then came the political revolution of the New Deal. Its long-range effects on the lives of the

Although the Republicans bounced back in 1938 and 1940, a new era had clearly begun. The 1940 and 1944 elections, dominated by war, were not a clear testing ground of longrange shifts. It was Truman’s surprise victory in 1948—after a 1946 postwar reaction had made the Eightieth Congress Republican—that confirmed the durability of the Roosevelt coalition and seemed to foreshadow a long and unbroken Democratic reign.

But that was deceptive. After World War II, nothing, including the party system, was or ever would be quite the same.

To recapitulate the ten presidential elections since 1952 does not in itself advance our understanding of the huge changes taking place in American political behavior. It merely reflects them. Loomine lamest is the curious result of the abandonment of straight-ticket voting at the federal level. Democrats have controlled the Congress almost uninterruptedly for those forty years. But they have won the presidency only three times, and only once (in 1964) resoundingly. John F. Kennedy, it is easy to forget, barely squeaked by in 1960, and so did Jimmy Carter in 1976. The result is an almost permanent and potentially paralyzing division of responsibility between Congress and the president beyond that which the Constitution already built in.

One often cited reason for the Democrats’ loss of control of the White House is the unraveling of the Roosevelt coalition. That does seem to have happened, and the dissolution of the old alliance into unreconciled factions is partly due to the party’s laudable efforts since the 1970s to open up its governing committees and nominating conventions to women, blacks, and other newcomers to the process. Praiseworthy or not, however, liberalizing the rules underscores all the old jokes about the Democratic tradition of disorganization.

The Republicans in the meantime appear to have

Such speculations aside, do the two mainstream parties stand for anything distinctively traceable to their historic ancestors? Would Alexander Hamilton, returned from his untimely grave, pose for a photo op with George Bush? Would Abraham Lincoln? Would Andrew Jackson or Woodrow Wilson take the stump for Bill Clinton? The question is better left open; both parties long ago accepted the reality of a strong national government with an overpowering impact on the economy through both policy and expenditures. And neither one can afford, politically, to avoid continuing federal engagement in promoting and sustaining the general welfare, the well-being of “the people,” through an infinite variety of existing social programs. Whatever the rhetoric, both incorporate elements of the Jeffersonian and Hamiltonian outlooks. And both have generally been bound, since 1945, by an unspoken agreement on bipartisanship in foreign affairs, which have—at least until now—been the overshadowing responsibility of the national government. On diplomatic and military issues the parties agree not to disagree.

This is a far cry from saying that they are identical. Vachel Lindsay, to get back to him, wrote of that 1896 campaign: “There were truths eternal in the gab and tittle-tattle/There were real heads broken in the fustian and the rattle.” That is still true in 1992, but the parties simply don’t get to the gut and bring people out to cheer and howl as they used to. There may be dozens of reasons: the welfare state that makes the old-time precinct workers’ handouts obsolete, TV image making, the importance of big funding, poll taking—all of them developments that put a premium on expertise in campaign management instead of enthusiasm in the streets and that therefore make the ordinary voter feel shut out. Or perhaps just a new electorate to whom politics isn’t the absorbing pastime that it was in another American time and culture.

Or maybe it’s I the triumph of that part of the progressive idea that lauded disinterested competence in government as ideal. I have heard a young scholar defend the nronosition that we necessarily live nowadays under government administered by bureaucratic elites and virtually professional lawmakers and that “citizen participation” consists of sending money to the lobby of one’s choice and expressing one’s opinion to the poll takers. He believes that democracy’s health is not all that endangered by so-called voter apathy.

Perhaps. Still, there is a historical paradox here. We have actually widened the base of democracy over the last three-quarters of a century. We have, by constitutional amendment, enfranchised women, eighteen-year-olds, and residents of the District of Columbia and re-enfranchised blacks. Presidential nominees are no longer chosen in the

Whatever the national parties do now in the way of framing political life through professional fund-raising and research, it is different from the days, to quote Lindsay one final time, of “all the funny circus silks of politics unfurled … and torchlights down the street, to the end of the world.” The bottles have the same label, but the vintage is new. The party organizers and party bosses, from Aaron Burr and Thurlow Weed and Mark Hanna to Richard Croker and James M. Curlev and Big Bill Thompson, came on the scene at a particular stage of national evolution that is now past. They gave democracy creations of splendor and shadow. And now they are gone with Bryan “where the kings and the slaves and the troubadours rest.”