Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

September 1992 | Volume 43, Issue 5

Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

September 1992 | Volume 43, Issue 5

“I’ve got a ballot, a magic little ballot,” sang supporters of Henry Wallace’s presidential campaign in 1948. ”… There is magic in that ballot when you vo-o-o-ote !”

Americans performed magic with their paper ballots for a long time. In fact, Massachusetts Puritans were electing governors by written ballots as early as 1634, influenced perhaps by city elections they had witnessed in the Netherlands. Most early voting, however, remained viva voce: in person and out loud. It was a very public act. Virginia electors announced their choices in the presence of the rival candidates, usually gaining an “imbibable” from the one they favored. When the printed ballot (locally called a prox) emerged in Rhode Island by 1744, its purpose was not secrecy but the convenience of voters unable to journey to Newport for election day.

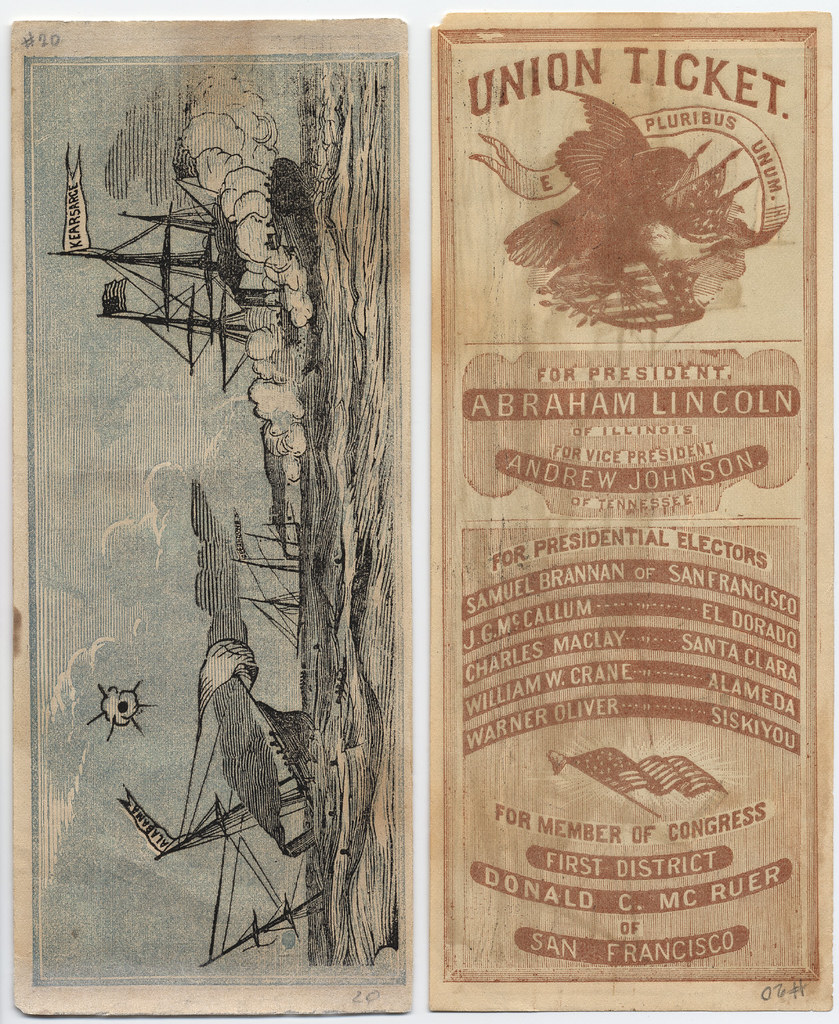

Long before the Revolution, ballots had evolved into the form we recognize today: a party’s candidates were listed from top to bottom in order of importance, from governor down to coroner. To lure voters, printers adorned their ballots with handsome ornaments and sometimes with a little propaganda. “Liberty, Property, & No Stamps,” reads a 1766 prox; in the next year a ballot tagged “Supporters of the Colony’s Plights” vied with one aimed at “Seekers of Peace.”

Viva voce remained the dominant mode of voting until the 1820s, when the growth of cities and the gradual extension of suffrage beyond prominent men of notoriety made change essential. Jeffersonians hoped that the paper ballot would constitute a secret vote that workmen might cast free of intimidation by their wealthy employers, but this wasn’t always the case. Some localities required separate ballot boxes for each party; others made voters sign their ballots.

As more and more offices became elective, ballots stretched longer; some grew so unwieldy that they had to be cut into national, state, and local segments. Modestly declining to vote for himself in 1860, Abraham Lincoln snipped off the national part at the top and voted only the state and local Illinois Republican slates.

Ballots acquired more elaborate graphics and propaganda during the nineteenth century, incorporating easily recognizable symbols of hot political issues or humorous vignettes. To accommodate illiterate voters, the ballots brandished familiar party emblems and portraits of the candidates. Maryland Democrats overworked a steadily deteriorating “Jackson and Liberty” woodcut for half a century; as a result some German-speaking farmers are said to have thought they were voting for Old Hickory many years after his death.

Such confusion wasn’t always accidental, for ward heelers found the paper ballot ideal for dirty tricks. The stratagem of printing bogus opposition ballots that were deliberately flawed so as to be thrown out had been perfected by 1764. In