Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

February/March 2021 | Volume 66, Issue 2

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

February/March 2021 | Volume 66, Issue 2

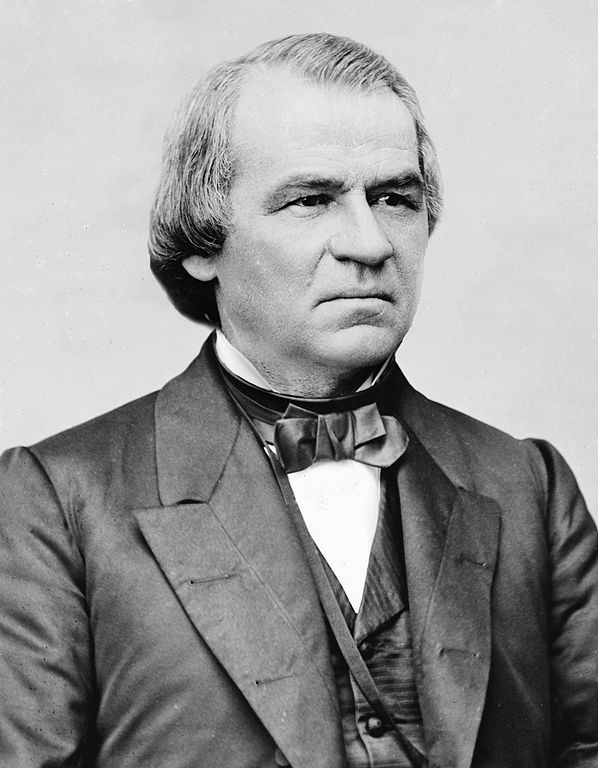

The administration of Andrew Johnson, which began upon Lincoln's assassination in April, 1865, was predominantly concerned with redefining the status and rights of people, both black and white, living in the defeated Confederate states. The strong differences over racial policies between Johnson and his opponents in Congress lie outside the scope of this study. Johnson asserted an ideological and constitutional position of great importance on May 29, 1865, when he issued his Amnesty Proclamation. Under its terms, the president used his pardoning power to restore effectively the political and economic rights of virtually all white southerners.

Of concern here is not this stand by Andrew Johnson, but allegations that Johnson abused his powers as president by not executing the laws of Congress. Many important expressions of Johnson's defiance were made without notice to Congress or the public. Charges of such abuses of power formed the subject of extensive hearings in 1867 held by the Judiciary Committee of the House of Representatives. The committee heard more than eighty-five witnesses conversant with conditions in the South and enforcement of federal law and took 1,154 pages of testimony.

See also “They Impeached Andrew Johnson,” by David Herbert Donald

The first major case of failure to carry out the presidential duty of enforcing an act of Congress occurred on August 16, 1865. Congress, on March 3, 1865, had passed legislation creating the Freedmen's Bureau in the executive branch. President Lincoln signed the bill. Under its terms, “the Commissioner, under the direction of the president," was authorized to “set apart” for “loyal refugees and freedmen” for the period of three years “not more than forty acres of lands abandoned within the insurrectionary states.” This implied a promise of 40 acres for about 20,000 freedmen families in the South.

On August 16, with notice only to the assistant commissioner of the bureau in Tennessee and to subordinate officers in the bureau headquarters in Washington (the commissioner was on vacation), Johnson ordered lands covered by the act of March 3 restored to a former landowner, B. B. Leake. On the back of a request for guidance in the matter, Johnson added that the “same action will be had in all similar cases." Almost casually, Congress's act was abrogated.

The appointive power lies with the president and extended, of course, over the Freedmen's Bureau. Investigating congressmen, however, charged that the power of appointment was abused when appointments were made for the specific purpose of frustrating rather than facilitating the enforcement of the law. Johnson replaced Thomas Conway, assistant commissioner for Louisiana, with James Scott Fullerton, and instructed Fullerton to report directly to him.

The president did this because Conway was prepared to execute the congressional land redistribution plan; Fullerton,