Authors:

Historic Era: Era 6: The Development of the Industrial United States (1870-1900)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

February/March 2021 | Volume 66, Issue 2

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 6: The Development of the Industrial United States (1870-1900)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

February/March 2021 | Volume 66, Issue 2

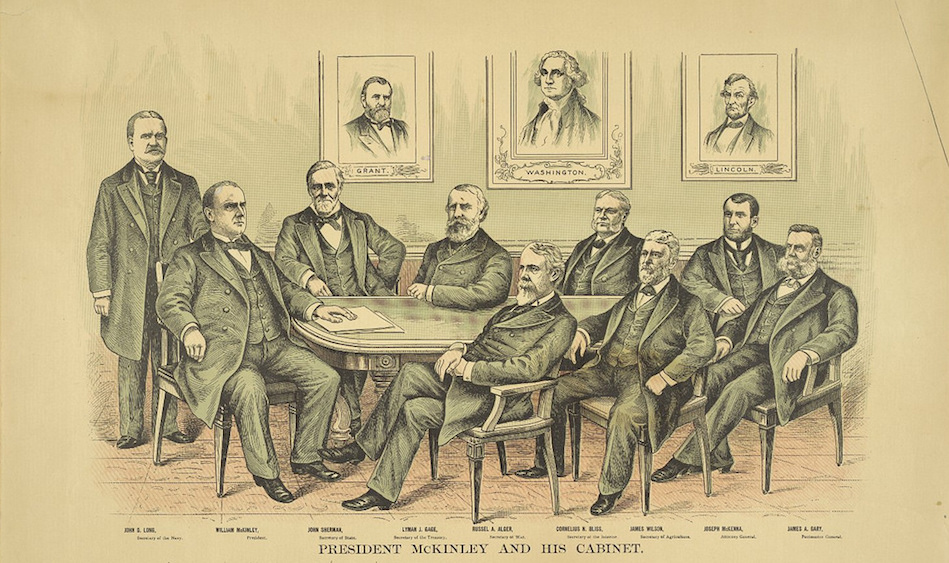

On September 8, 1898, Secretary of War Russell A. Alger formally petitioned President William McKinley for an investigation into the War Department's conduct of the war with Spain. For months Alger had been the target of a crescendo of criticism and verbal abuse arising out of the confusion that marred the American war effort from start to finish. The range of criticism is suggested in Alger's request that the inquiry examine such matters as mobilization, supply transportation, military contracts, all expenditures, orders emanating from the War Department--in short, everything connected with the army during the brief conflict except grand strategy and tactics.

McKinley quickly approved the request, and on September 24 he announced that a voluntary commission of military men and civilians would conduct the investigation. His first choice to head the commission, Lieutenant General John M. Schofield, suspected that the inquiry was a political ploy and declined to serve. McKinley then recruited General Grenville M. Dodge, a prominent Republican businessman and Civil War veteran, who had long been a friend and defender of Alger.

Alger was a poor choice to head the War Department. A former governor of Michigan and past commander in chief of the Grand Army of the Republic, he had been picked purely for political reasons. Genial and self-confident, he knew nothing about the War Department, and during the year following his appointment he did almost nothing to prepare the army for a war whose coming he could hardly have failed to anticipate.

Admittedly, the task he faced was a gargantuan one. For decades the American people had badly neglected the army. By 1898 it was riddled with stuffy traditionalism, petty jealousies, and bureaucratic lethargy. The wonder is that it performed as well as it did and managed to reform itself pragmatically as the war progressed. Given the American military posture in 1898, it was all but inevitable that the war effort should have been marked by confusion and bungling. Of his own role in the disarray, Alger plaintively observed that “the life of the Secretary of War was not a happy one in those days of active military operations.”

Early in the war, McKinley began to suspect that Alger was an ineffective war minister—and so did the press and members of Congress. As early as May 18, the New York Times demanded that Alger be removed. But while McKinley lost confidence in him and consistently bypassed him in dealing with the army command, especially in matters of strategy, he retained him in office and publicly supported him.

The earliest indications that the outdated military system was in