Authors:

Historic Era: Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2020 | Volume 64, Issue 1

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2020 | Volume 64, Issue 1

The two hundred men John Smith left behind him in the fort may not have been well trained or organized, but they were a determined bunch. Beneath the dirt and grime and stubble and rags was a group who had been tested and not found wanting. Many of them had been among the first to answer the call, to join Stephen Austin’s Army of the People.

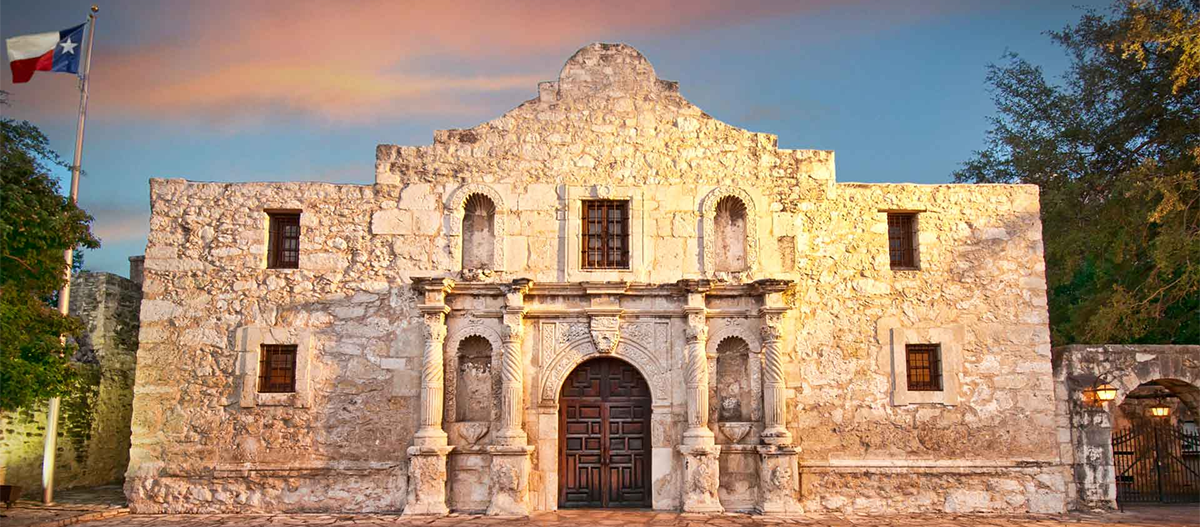

Read the full dramatic story in "Storming of the Alamo," by Charles Ramsdell, Jr.

These militiamen had hurried to Gonzales at the first request for help and endured much for the cause. They had marched to Bexar and remained there, in cold and rain and wretched conditions, for many weeks. They had stormed the town in the predawn hours of December 5 with Milam and Johnson and Grant, running through the dark cornfields and streets to gain a tenuous foothold on the well-fortified town held by the Mexican army, a much larger, better organized, and better equipped force, battling house by house and room by room for five grueling days.

Some of the colonists had left then, when Martín Perfecto de Cós had surrendered and marched his eleven hundred soldiers out of Texas — gone home to their families and farms. The war was over; they could return to their lives, at least until spring.

Most of the volunteers from the United States, such as the New Orleans Greys, were young men with no homes to return to. They had left their homes for Texas in response to the call for aid and arrived weeks later to assist their Texian cousins in the ousting of a despot — much as their fathers and grandfathers sixty years before them had rebelled against George III. They saw this cause as similar, the parallels too strong to ignore: a tyrannical dictator running roughshod over the rights of his subjects and violating the covenant accepted by the immigrants and residents alike, whether Anglo or Tejano. Taxation without proper representation, and a complete lack of a representative political system upon the dissolution of the state congresses ... the abrogation of the most basic of civil rights, including the absence of trial by jury and the writ of habeas corpus ... military occupation that threatened to increase dramatically ... the insistence that the colonists deliver up their arms — such burdens these sons of 1776 found intolerable.

So these men had come to Texas to fight for liberty, and also to gain the land that would make them truly free men, earning their living independent of any other and providing a better life for themselves and their families. And they thought these things worth dying for.

The American Revolution had been the first great uprising