Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2020 | Volume 64, Issue 1

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2020 | Volume 64, Issue 1

Editor's Note: Professor Dick Howard has been in a unique position to see first-hand the impact of the ideas of our Founders around the world. Since he was executive director of the commission that wrote a new constitution for the Commonwealth of Virginia in 1971, Howard has consulted with 15 countries in writing their constitutions including Albania, Brazil, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland, Hong Kong, Romania, Russia, Malawi, South Africa, and the Philippines. He is now the White Burkett Miller Professor of Law and Public Affairs at the University of Virginia.

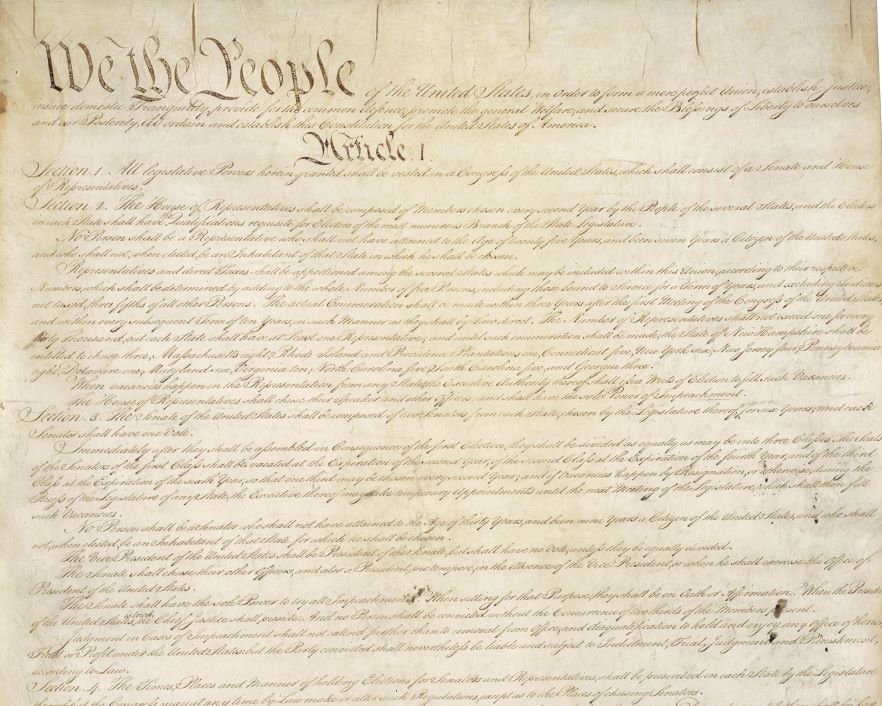

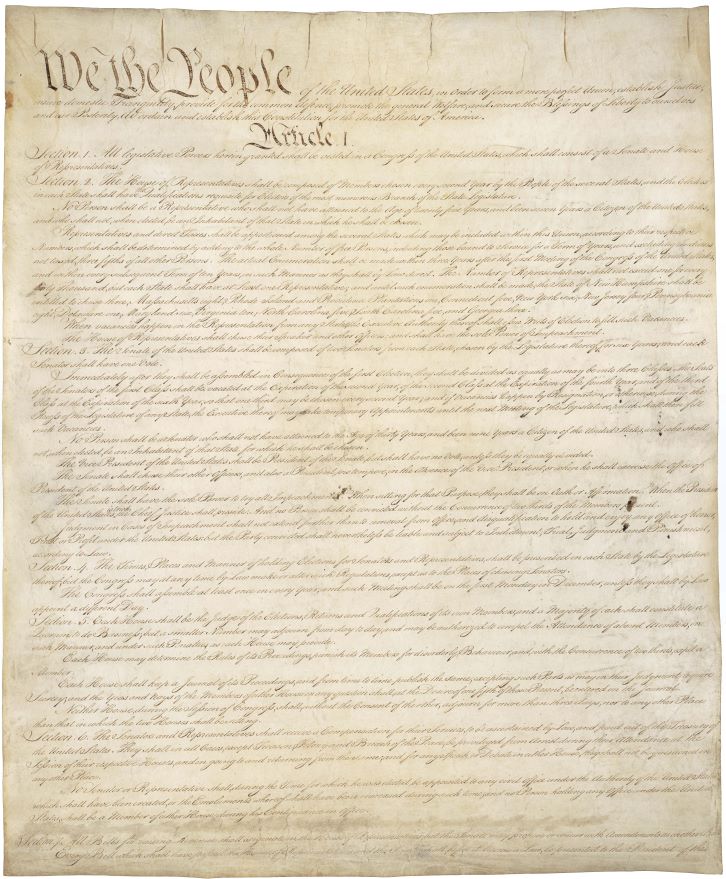

The delegates who signed their names to the Declaration of Independence in July 1776 knew that they had an audience beyond the King and Parliament in Great Britain. They declared that a “decent Respect to the Opinions of Mankind” obliged them to specify the nature of the grievances which led them to declare independence. Indeed, by basing their case on “the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God,” the American drafters assumed a world of values not limited to the Anglo-American sphere.

Americans of that era were not mistaken in supposing that the ship they were launching was undertaking a voyage of interest far beyond their own borders. What an exciting time it was. America in the founding generation produced ideas about constitutions and constitutionalism that have had lasting influence at home and abroad. Among those ideas were devising ways to ensure the supremacy of constitutions over ordinary laws, envisioning conventions designed specifically to write a constitution, fashioning the separation of powers and checks and balances so as to nurture the rule of law, and giving reality to the Madisonian argument that a republic did not have to be small in order to survive.

America at the close of the 18th century was, to be sure, different in many ways from the mother country and, more generally, from Europe. America was by the time of the Revolution already more democratic. The public sphere was markedly different. There was no monarchy. There was, at the national level, no bureaucracy. For most people, politics and government were local. There was not a nobility or, indeed, a legally constituted social order. And, while states had established churches, already the strictures of establishment were weakening.

Even so, the founding years of American constitutionalism engendered intense interest throughout the Atlantic world. For years, philosophers, especially in France, had talked of liberty and equality. Now they could look to Americans as putting those ideas into actual practice. Condorcet declared that it was not enough “that the rights of man be written in the books of philosophers.” A real-world example was needed: “America has given us this example.”

Beginning in 1776, French and American thinkers debated what a constitutional regime should look like. In France, Turgot objected to American state