Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

September/October 2019 | Volume 64, Issue 4

Authors: Joseph J. Ellis

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

September/October 2019 | Volume 64, Issue 4

Editor's Note: We asked Joseph Ellis, one of the leading scholars on the Founding era, to provide us with historical content for the Second Amendment and what the founders intended when they wrote it. Ellis won the 2001 Pulitzer Prize for History for Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation and the National Book Award for American Sphinx: The Character of Thomas Jefferson, both of which were New York Times bestsellers. Portions of this essay appeared in his most recent book, American Dialogue: The Founders and Us.

With the recent tragic shootings, the time has come to reexamine carefully the Second Amendment and its interpretation. In 2008 the Supreme Court overturned two centuries of legal precedents to find in District of Columbia v. Heller that the Second Amendment sanctioned the right to own and carry a gun except in the rarest of circumstances. The majority opinion was written by Justice Antonin Scalia, the most outspoken originalist on the court, who described Heller as his magnum opus, “the most complete originalist opinion that I have ever written.”

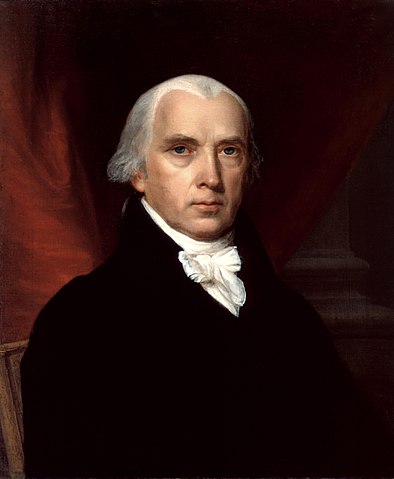

How does Scalia's opinion stand up as an accurate rendering of James Madison's intentions in 1789, when he drafted the Second Amendment? What did the term “bear arms” mean to the Revolutionary generation? What was the historical context in the Congress that endorsed the Second Amendment and the states that ratified it?

Fortunately, there is an impressive body of evidence in the historical record to permit a faithful rendering of what the Second Amendment originally meant, both to its authors and its audience.

In the often bitter debates over ratification in 1788, many Anti-Federalists had agreed to vote for the new Constitution only if Congress would agree that guarantees of certain personal freedoms and additional limitations on the Federal government's power would be included in a set of amendments — what later became known as the Bill of Rights. One section in the Constitution that had caused these critics particular concern was the language in Article 1, Section 8 which gave Congress the power to “provide for the common Defense and general Welfare of the United States.”

The critics saw an ominous projection of federal jurisdiction over the militia-based military establishments of the individual states: first, they were worried about giving Congress the authority “to raise and support armies” (despite the

This caused so much concern that five states recommended an amendment calling for the prohibition of a national standing army on the grounds that such military forces had historically proven to be an enduring threat to republican values.

In the Virginia convention to ratify the Constitution, Madison was forced to listen as Patrick Henry conjured up apocalyptic scenarios in which the Virginia militia were ordered out of the state to support military operations in faraway places that citizens of the Old Dominion considered misguided deployments in foreign countries.

One of the recommended amendments Virginia submitted for consideration in 1788 reflected Henry’s concern on this score, drawing on language that had been contained in the Declaration of Rights in its own state constitution passed on June 26, 1776: “The people have a right to keep and bear arms; that a well-regulated militia composed of the body of the people trained to arms is the proper national, natural, and safe defense of a free state. That standing armies in times of peace are dangerous to liberty, and therefore ought to be avoided.”

Madison clearly had Virginia’s recommended amendment on his desk and in his mind when he drafted the following words for an amendment: “The right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed; a well armed and well regulated militia being the best security of a free country….” For unspecified reasons, the Senate reversed the first two clauses in Madison’s draft, which grammatically clarified the rationale for the right to bear arms. Thus the Second Amendment reads: “A well regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to bear arms, shall not be infringed.”

By nodding toward a primary role for the militia, Madison had appeased some of his Antifederalist critics, but he had not satisfied those like Henry who wanted an unambiguous statement that the state legislatures, not the Congress, enjoyed sovereign control over their own citizenry in times of war. Creating ambiguity, in fact, was the centerpiece of Madison’s political agenda.

During the debates over ratification that ensued in the House and Senate, as well as in those state legislatures that kept a record, considerable attention focused on a current proposal from Secretary of War Henry Knox, calling for a professional army of unspecified size, which opponents described as a violation of the Second Amendment.

In 1792, soon after the first ten amendments were ratified, Congress passed

For those disposed to unpack the Second Amendment for the original meaning of “bear arms,” it has collective implications that lead not toward the right to own a gun, but toward mandatory national service. In that sense, both Madison and the critics he sought to appease were living in a world forever lost to us.

Read more about the debates between Patrick Henry and James Madison over ratification of the Constitution in “Patrick Henry Smells a Rat,” by Paul Aron

# # #

There is a fundamental difference between advocates of a “Living Constitution” and originalists. The former could plausibly find reasons to expand a woman’s right to choose, make health care a right of citizenship, and reject all state laws prohibiting gay marriage. Ardent originalists could plausibly find both Roe v. Wade and Brown v. Board of Education unconstitutional, as well as all New Deal legislation that empowered the federal government to regulate the economy in redistributive ways, to include Social Security. It had become received wisdom that the single most consequential power of the presidency was now the power to nominate judges to the Supreme Court.

The political direction of the conservative court became clear in a couple of controversial decisions. In Bush v. Gore (2001), the new conservative majority read the tea leaves of a baffling Florida statute in such a way as to award the presidency to George W. Bush, the only time in American history that the Supreme Court had exercised that power. And then in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (2010), this time overturning a century of precedents, the court found that all federal restrictions on corporate giving to political campaigns were unconstitutional violations of the First Amendment right to free speech.

Taken together, or perhaps taken one after the other, the liberal and conservative waves of lawmaking gave the Supreme Court a conspicuous place of prominence in our political culture. It came at a price. For most of American history, the court had enjoyed special status as the one branch of government that levitated above the hurly-burly of partisan politics in some transcendent realm reserved for demigods. The Supreme Court, in effect, enjoyed the same kind of privileged treatment that was accorded the founding generation. In both cases a kind of electromagnetic field surrounded both the judges on our highest court and the political elite that was “present at the creation.”

Supreme Court in 1986 while President Reagan looked on. After his retirement, the conservative Burger stated that the Second Amendment "has been the subject of one of the greatest pieces of fraud, I repeat the word 'fraud,' on the American public by special interest groups."" data-entity-type="file" data-entity-uuid="935af0c0-1893-43f1-b134-6fdfdfc8f241" height="391" src="https://www.americanheritage.com/sites/default/files/inline-images/The_Swearing-In_Ceremony_for_Antonin_Scalia2.jpg" width="788" loading="lazy">

One of the most seductive appeals of the originalist persuasion was the claim to derive its judicial insights from founders who allegedly enjoyed privileged access to eternal truths. After all, why ascribe such enduring significance to the original words or intentions of the framers if you did not regard them, or the historical moment in which they lived, as semi-sacred? Both deifications were always illusions, though extremely useful ones. For the same bundle of reasons that most mortals need to believe in eternity, most new nations require mythical heroes. Similarly, it is comforting to believe that all controversial and divisive political questions can be sent to a trusted tribunal composed of godlike judges who possess a preternatural affinity for the truth.

Whatever useful purposes such illusions might have once served, over the past half-century the scholarship on the founders and the blatantly political character of the Supreme Court makes them untenable. The American founding, most especially the drafting and ratification of the Constitution, was always a messy moment populated by mere mortals, whose chief task was to fashion a series of artful political compromises. And the Supreme Court had never floated above the American political landscape like a disembodied cloud of heavenly wisdom. It always was a political institution comprised of human beings with no special connection to the divine. Both illusions were now exposed as childish fables.

In the ongoing debate between advocates of a “Living Constitution” and originalists, several mitigating factors prevent the most extreme version of each doctrinal position from coming into play. The vast majority of Supreme Court decisions do not involve significant constitutional issues with vast historical consequences, and in many of those cases the votes are often unanimous opinions that defy doctrinal adjudication.

There is also an unspoken understanding among judges on both sides of the political divide that the court should only rarely impose its verdicts in opposition to widespread public opinion, though both Brown and Citizens United are exceptions to this rule. For example, liberals were predisposed to wait for a sufficient number of lower court decisions on gay rights before ruling on that controversial question. And conservatives recognize that it would be politically dangerous to deploy their originalist arguments against Brown

That said, there is a fundamental difference between the two sides of this judicial debate. The liberal devotees of a “Living Constitution” are transparent about their political agenda, but the conservative originalists are not. While the judicial doctrine of the originalists was explicitly designed as a weapon to overturn liberal precedents, its core claim is its assiduous political detachment. At least on the face of it, that claim is incompatible with the series of one-sided decisions made by the conservative majority in the twenty-first century. This was the reason why the usually understated Justice William Brennan described originalism as “arrogance cloaked as humility.”

The fullest illustration of the originalist approach in its purest form is the decision by Justice Antonin Scalia in District of Columbia v. Heller (2008). Scalia, the most outspoken advocate for the originalist doctrine on the Supreme Court, described Heller “the most complete originalist opinion that I have ever written.”

The case could have been decided on narrower, less expansive grounds. Joseph Heller was a security guard who wanted to bring his handgun home for self-defense but was prohibited from doing so by restrictions on handguns imposed by the District of Columbia, which included mandatory trigger locks. But Scalia and other conservative members of the court were in fact looking for an opportunity to expand the interpretation of the Second Amendment. The decision to hear the Heller case represented a recognition that the legal opportunity to achieve that goal had arrived. Assigning the majority opinion to Scalia ensured a verdict for the originalist persuasion.

Context is crucial. Heller was not some surprising airburst in the night but the culmination of a decades-long campaign orchestrated and funded by the National Rifle Association (NRA) to make gun ownership a right of citizenship. In that sense, Heller was to the conservative cause what Brown was to the liberal cause. Just as the NAACP waged a long legal and political battle against racial segregation that culminated in the Supreme Court decision that ended segregation by race in public schools, the NRA waged a similar and more heavily funded campaign to remove all legal restrictions on the right to purchase, own, and carry guns. Both Brown and Heller represented the final triumph in a long-standing, well-disciplined, highly organized struggle that both the NAACP and NRA knew could end only at the Supreme Court.

In retrospect, given what the NRA was up against, the speed of its successful campaign is stunning. Throughout the 1960s, polls showed that between 50 and 60 percent of Americans favored an outright ban on handguns. Moreover, judicial opinion on the Second Amendment was considered “settled law,” meaning that all the legal precedents, most recently synthesized in U.S. v. Miller (1939), found that the right to bear arms in the Second Amendment was conditional upon

But the political templates were already shifting, thanks in part to relentless pressure from NRA spokesmen but mostly because the newfound right to bear arms coincided with the libertarian agenda of the New Right, subsidized by the unprecedented flow of money provided by the Koch brothers and their conservative think tanks. As early as 1980, the Republican platform proclaimed its conversion: “We believe the right of citizens to keep and bear arms must be preserved. Accordingly, we oppose federal registration of firearms.” A year later Senator Orrin Hatch, chair of the Judiciary Committee, announced the new Republican dogma that “the Second Amendment sanctioned an individual right to keep and carry arms.”

As the ideological message of the New Right moved from the fringe to the center of the Republican Party, the more expansive version of the Second Amendment became the acid test for the antigovernment agenda. The great fear in this rendering was that government agents were coming to take your guns. By 2008, on the eve of the Heller decision, a Gallup poll showed that 73 percent of the citizenry believed the Second Amendment “guaranteed the right of Americans to own guns.” By then it had become rude to notice that the words on the plaque at NRA headquarters — “the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed” — had deleted the preceding clause about service in the militia.

One wing of the conservative campaign to capture public opinion focused its efforts on the law schools. In the 1990s the NRA paid three lawyers nearly $1 million to write thirty articles for law reviews, all designed to generate an alternative body of legal scholarship. Unlike historical journals, where submissions must undergo peer review, law school publications are run by students, so there is no editorial screening provided by academic professionals in the field.

The result was a new wave of legal and historical scholarship of dubious accuracy, multiple misquotations, and sometimes comical conclusions that its advocates began to call the “Standard Model.” The term described a set of shared historical distortions that soon began to invoke, then to celebrate, an unambiguous right to own guns.

Within this new historical universe, for example, the English Bill of Rights (1688) purportedly declared that all Englishmen enjoyed the right to bear arms. In fact, the Glorious Revolution restored the right to bear arms to Protestants

It also became received wisdom that the Second Amendment was in part motivated by bitter memories of British patrols going house to house during the American Revolution, disarming potential rebels. But there is no record of any such confiscations of muskets ever occurring before or during the war.

Patrick Henry became a new hero, and the NRA paid $1 million to endow a chair in his name at George Mason Law School with a plaque quoting Henry’s famous words: “the great object is that every man is armed.” Unfortunately, Henry never said that. The misquotation comes from a speech in which Henry was complaining about the excessive cost of arming a large militia. Nor did Henry ever say, as some publicity for the endowed chair claimed, that “they want to take away your guns.” At the Virginia ratifying convention he did say, reportedly to gales of laughter, “They’ll take your niggers from you.”

By the time Antonin Scalia and his law clerks began to draft what became the majority opinion in Heller, public opinion on the meaning of the Second Amendment had shifted dramatically. Thanks to the orchestrated efforts by the NRA, with an able assist from the bottomless coffers of libertarian philanthropists and their think tanks on the New Right, a more expansive understanding of the Second Amendment had become the new political orthodoxy. Within the Republican Party it was now an unquestionable article of faith. And even Democratic candidates for national office were required to skirt the edges of the gun issue. Moreover, an impressive body of new evidence had been deftly planted in the legal scholarship that was now available for harvesting by assiduous law clerks with a clear set of marching orders.

Read the majority opinion in Heller written by Justice Scalia included in its entirely in this issue

If that is the proper context for understanding the Heller decision, the ironies abound. For while Scalia went to his grave devoutly believing that Heller was the ultimate expression of his originalist philosophy of jurisprudence, it was in fact an excellent example of the principle of a “Living Constitution,” the very approach he denigrated and despised. Reva Siegel of Yale Law School was the first to point out the irony of it all by noticing that the argument made in Heller depended almost entirely on legal evidence generated in recent decades and, most blatantly, on the shift in popular opinion toward gun ownership over the same time.

The deeper truth, which Scalia had devoted his entire career to denying, was that all judges, like all historians, cannot escape the fact that they are viewing the past through the prism of the present. And Heller represented the judicial version of a new understanding of the Second Amendment, albeit an understanding achieved in a deftly orchestrated fashion. In that sense, all judges,

That said, it was in fact possible to render an originalist interpretation of the Second Amendment in Heller. There is no need to conjure up such an opinion because Justice John Paul Stevens wrote it in his impassioned dissent. “The Second Amendment was adopted to protect the right of the people of each of the several states to maintain a well-regulated militia,” he declared.

It was a response to concerns raised during the ratification of the Constitution that the power of Congress to disarm the state militias and create a national standing army posed an intolerable threat to the sovereignty of the several states. Neither the text of the Amendment nor the arguments advanced by its proponents evidenced the slightest interest in limiting any legislature’s authority to regulate private civilian uses of firearms. Specifically, there is no indication that the Framers of the Amendment intended to enshrine the common-law right of self-defense in the Constitution.

Read the dissent in Heller by Justice Stevens included in this issue

With a few minor caveats, Stevens’s opinion accurately summarizes what Madison and his fellow founders thought they were doing when they wrote and ratified the Second Amendment.

It is somewhat misleading to claim they were concerned that Congress wished “to disarm the state militias.” The concern was rooted in the fear that a national army would render militias irrelevant.

What Stevens described as “the common-law right of self-defense” also suggests a clear principle of individual rights only problematically present in the eighteenth century.

Nevertheless, the Stevens opinion correctly synthesized the historical evidence in a way that recovered the original meaning of the Second Amendment as it was understood by the authors and the larger audience of readers and listeners at the time. It is the originalist opinion of the Supreme Court in Heller. The problem, of course, is that an originalist opinion did not permit the more expansive understanding of the Second Amendment that a long-standing member of the NRA named Antonin Scalia, soaked in the evidence it had so diligently assembled, could find credible.

This collision between Scalia’s originalist convictions and his political agenda helps explain why his opinion in Heller is so difficult to follow, indeed seems almost designed to create a maze of labyrinthian pathways that crisscross, then double back on one another like a road map through Alice in Wonderland. For Scalia was committed to providing an originalist reading of a historical document whose words and historical context defied the conclusion he was predisposed to reach.

If Heller reads like a prolonged exercise in legalistic legerdemain, or perhaps a tortured display of verbal

Scalia began his opinion in Heller by distinguishing between what he called the “prefatory clause” and the “operative clause” of the Second Amendment. He then declared that “the former does not limit the latter grammatically but rather announces a purpose. “It soon became clear that this distinction was a verbal version of judo with more than acrobatic implications, for it redefined the syntax of the Second Amendment. The words “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free state” were transformed into a merely rhetorical overture.

In Scalia’s parsing of the text, the militia requirement imposed no limitations on “the right of the people to keep and bear arms.” The fact that announcing a purpose explicitly imposed limiting conditions was lost in translation. The Scalia version of the Second Amendment, much like the plaque at NRA headquarters, lopped off the militia requirement as an irrelevant prologue, leaving only the individual right to bear arms as the full and true meaning of the amendment. The game is essentially over at the very start in Heller, for with this singular act of editorial magic, the stated rationale for bearing arms disappears.

There was still the nettlesome question of context, chiefly Madison’s motives for drafting the Second Amendment, the debates and revisions made in the House and Senate, then the ratification debates in the state legislatures. A good deal of potential trouble lay along that path, since the militia question and the fear of a standing army, sometimes referred to as a “select militia,” dominate the historical record. Scalia handled this inconvenient evidence with a dismissive wave of the hand: “The Second Amendment’s drafting history [was] of dubious interpretive worth.”

A slightly less cavalier attitude emerged when Scalia confronted the precedents that Heller was overturning. These were four previous Supreme Court rulings on the Second Amendment. The most recent, U.S. v. Miller (1939), reaffirmed the conclusion reached in the three earlier cases, that the right to bear arms was not an individual right but rather a right dependent on service in the militia.

Although Scalia’s argument in Heller was a direct refutation of what had previously been considered “settled law,” he devoted seven pages to a review of his Supreme Court predecessors before reaching the extraordinary conclusion that “none of the Court’s precedents forecloses the Court’s interpretation.” Scalia clearly needed to believe that he was operating within the bounds of stare decisis, even though he clearly was not.

Heller goes on for many pages, making it one of the longer majority opinions in Supreme Court history. Scalia obviously believed that he was creating his masterpiece, and his zealous clerks provided him with a massive amount of historical evidence he could not resist quoting at length. Many of the citations are drawn from English and American dictionaries of the period, though the analysis wanders well beyond the founding era to the Civil War and its aftermath for reasons never explained. The prose becomes tedious, even tortured, as when the phrase “the right to bear arms” is parsed to explain the separate meanings of “right,” “bear,” and “arms.”

Scalia was determined to demonstrate that the crucial phrase had more than a merely military meaning. His researchers found that the state constitutions of Pennsylvania and Vermont explicitly mentioned “self defense” as a rationale, primarily because backwoods residents in those states needed their muskets to fend off Indian attacks. That was all Scalia needed to clinch his point, the proverbial exception that proved the rule.

A database survey of the published correspondence for the eight most prominent founders revealed that they used the words “bear arms” 150 times, on all occasions referring to service in the military. To be fair, not that it would have made any difference, the survey was not available at the time Scalia wrote Heller.

# # #

Scalia was not a historian and never claimed to be. But as the preeminent proponent for originalism as a judicial doctrine, he claimed to base his interpretations of the Constitution on historical grounds, which for originalists entailed recovering the mentality and language of the framers on their own terms in their own time. Whether he knew it or not, this commitment imposed a disciplinary standard of attempted detachment and an analytical framework in which a preferred outcome must not be permitted to dictate the research agenda.

Scalia’s opinion in Heller openly and unapologetically violated those core convictions of the historian’s craft. He began with the presumption that the right to bear arms was a nearly unlimited individual right, assembled evidence to support that conclusion, and suppressed or dismissed evidence that did not. Nor did he attempt to conceal what he was doing. Indeed, he subsequently called attention to the intellectual agility and debater-like skills required to make his case. The problem that Scalia faced in Heller was that the preponderance of historical evidence went against his case, which was all the more reason why he was so pleased with his acrobatic performance.

Scalia’s methodology in Heller is a textbook example of what constitutional scholars have called “law office history,” which assumes that the suppression of evidence harmful to your client is not only

Historians are not required to think in such binary terms. And their “on the one hand, on the other hand “judgments, or paradoxical conclusions that fit both sides or neither side of an up-or-down verdict, are the earmarks of their commitment to detachment. While Scalia’s lawyer-like reasoning process in Heller is tolerated, accepted, even admired by many legal scholars, professional historians view it quite differently, regarding it as a flagrant violation of the canons of their craft.

From the historian’s perspective, Heller is most revealing for what it exposes about originalism as a judicial philosophy. It is not just that there is no single source of constitutional truth back there at the founding to be discovered. Nor is the major problem the hubris required to claim a preternatural affinity for divining the truth that no previous members of the Supreme Court have ever possessed. The great sin of the originalists is not to harbor a political agenda but to claim they do not, and to base that claim on a level of historical understanding they demonstrably do not possess.

# # #

Anyone seeking inoculation against the seductive charms of originalism need only follow James Madison on his evolutionary odyssey from 1786 to 1789. All clairvoyant visions of any singular intent or meaning of the Constitution will dissolve within the shifting contexts, unforeseen obstacles, and uncomfortable compromises of that Madisonian moment.

There is, in truth, an impressive body of knowledge back there at the founding available for recovery, but only originalists genuinely interested in listening to both sides of the American Dialogue in its original version will live up to the full meaning of their own declared intentions. A few members of the Federalist Society fit that description, but the vast majority, and all recent appointees to the Supreme Court, are fixated on the antigovernment side of the dialogue.

They are deaf to the pro-government voices of John Adams, Alexander Hamilton, John Marshall, and the younger James Madison. Their one-sided version of originalism was in fact designed to impose limitations on federal authority over the marketplace and to expand the range of corporate power. That is the reason why they were appointed to the Supreme Court by Republican presidents, and the reason why their landmark decisions align almost perfectly with the conservative agenda.

If a full-blooded originalist were ever appointed to the court, her or his opinions would be difficult to predict, because they would more accurately reflect the broader argumentative context of the founding era. Such a rare creature could even

At present, however, the originalist justices on the Supreme Court practice the narrower version of that doctrinal persuasion. To repeat, they would not occupy their powerful and privileged posts if they thought otherwise. This presents a serious problem, eerily reminiscent of the dilemma Franklin Roosevelt faced during his second term. At a time when America’s infrastructure is aging badly, when whole regions of rural America are unprepared to compete in a globalized economy, when both the middle class and the coral reefs are eroding, a national response to those challenges will prove extremely difficult to orchestrate because a tiny group of judges will say the federal government cannot perform that role. They will express regret at the unfortunate implications of their decisions but claim that their hands are tied.

The fate of 320 million Americans will be decided by five judges who, citing nineteenth-century dictionaries to translate words from an eighteenth-century document, misguidedly claim they are only channeling the wisdom of the founders.