Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Fall 2019 - George Washington Prize Books | Volume 64, Issue 5

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Fall 2019 - George Washington Prize Books | Volume 64, Issue 5

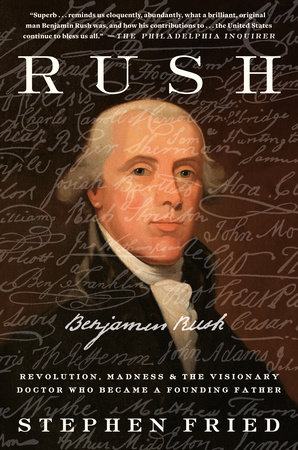

Excerpted from the George Washington Book Prize finalist Rush: Revolution, Madness, and Benjamin Rush, the Visionary Doctor Who Became a Founding Father, by Stephen Fried.

In the late morning of August 29, 1774, a well-worn carriage made its way down dusty King’s Highway, along the Pennsylvania side of the Delaware River just below Trenton.

In the carriage were the four members of the Massachusetts delegation to the first Continental Congress—including John Adams, a scruffy, gregarious thirty-eight-year-old lawyer, who was extremely anxious about the future of his country. He had written to his wife, Abigail, the evening before about how it would feel to finally arrive in Philadelphia at the “Theatre of Action,” where he hoped that “God Almighty” would grant him and his colleagues “Wisdom and Virtue sufficient for the high Trust that is devolved upon Us.”

But Adams also had some less lofty concerns. After more than two weeks on the road during the sultriest time of the year, he was sweaty and stinky and in desperate need of clean clothes. He had six shirts, five pairs of stockings, two caps, a pair of worsted stockings, and one silk handkerchief awaiting a laundress the moment they got to town.

Their carriage soon arrived in the farm town of Frankford, five miles north of the city, where Adams and his group were to be met by a local delegation. They presumed these would be like-minded Pennsylvanians who believed in the cause of freedom from England and would laud their bravery; Massachusetts was, so far, the primary place where colonists and British troops had clashed. The delegation also included John’s older cousin Samuel, a leader of the Sons of Liberty, who had instigated the recent Boston Tea Party.

Instead, the Philadelphians, after exchanging pleasantries and bringing the New Englanders to a nearby apartment for drinks in a private room, proceeded to tell their guests the last thing they expected to hear.

“You must not utter the word ‘Independence,’ nor give the least hint or insinuation of the idea, neither in Congress or any private conversation,” Adams would later recall being warned. “If you do, you are undone.” If they wanted this historic meeting of colonies to make any progress, the Philadelphians insisted, they needed to shut up with all their open talk about liberty.

Their hosts also lectured Adams and his colleagues about strategy. While they were “the representatives of the suffering state” and might reasonably expect to speak loudest, the Philadelphians advised that “you must not pretend to take the lead.” Virginia, the largest colony, would be the key actor in bringing the southern and middle colonies into a union, and the Virginians would need to feel they were in charge. Adams and his colleagues had to suck it up and