Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2020 | Volume 64, Issue 1

Authors: Fergus M. Bordewich

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2020 | Volume 64, Issue 1

The first Congress may have been the most important in American history, establishing how our new government would work based on principles that had been only broadly outlined in the Constitution. We asked the distinguished historian Fergus Bordewich to provide us with an overview of the first two years of the U.S. Congress and the challenges it faced. Portions of this essay appeared in Mr. Bordewich's recent book, The First Congress. His new book, Congress at War, due out in February 2020, will focus on how Congress helped win the Civil War.

--The Editors

Had the first federal Congress failed in its work, the United States as we know it today would not exist. Beginning less than two years after the conclusion of the Constitutional Convention and before all 13 states had ratified that document, the first Congress was charged with creating a new government almost from scratch.

No one, neither in Congress nor outside, knew if it would or could succeed when it first assembled at Federal Hall in March 1789. How it did so over the next two years is an epic story of political combat, vivid personalities, clashing idealisms, and extraordinary determination. It breathed life into the Constitution, established precedents that still guide the nation’s government, and set the stage for political battles that continue to be fought out across the political landscape of the twenty-first century: sectional rivalry, literal versus flexible interpretations of the Constitution, conflict between federal power and states’ rights, tensions among the three branches of government, the protection of individual rights, the challenge of achieving compromise across wide ideological chasms, suspicion of “big money” and financial manipulators, hostility to taxation, the nature of a military establishment, and widespread suspicion of strong government.

Confidence in government was abysmally low. Since the end of the Revolutionary War in 1783, Congress had struggled to govern, with little actual power and even less respect. Along with many disgruntled Americans, newly elected South Carolina senator Ralph Izard complained to Thomas Jefferson of “the humiliating state into which we are plunged. The evil has arisen principally from the want of an efficient & energetic government, pervading every part of the United States.”

Contempt for politicians was rife: a New Englander transplanted to Georgia groaned, “The people here are as depraved as they are in Rhode Island, for Most of the Offices in the State are filled by the worst characters in it.” Many political men held

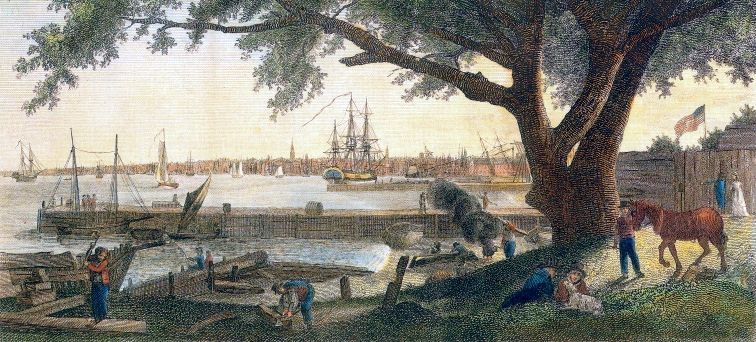

In the late winter of 1789, the United States had only a ghost of government. The rump end of the Confederation Congress still wobbled along in New York City, where it had met since 1785, but it hadn’t achieved a quorum since October. Its secretary, Charles Thomson, buttonholed members on the street when he could find them, and dragged them into his office so that he could claim in his records that they had, technically, “assembled.”

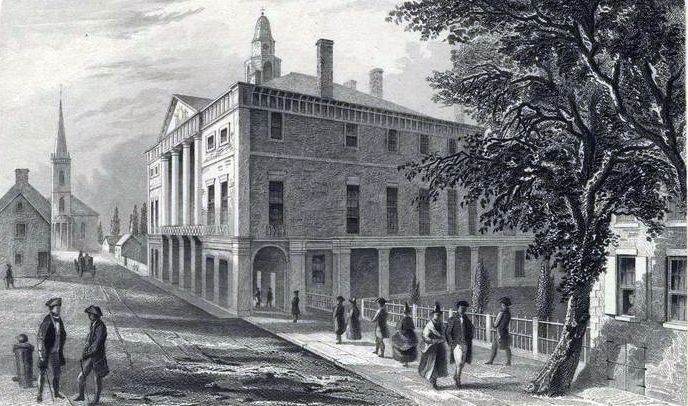

The old Congress, though not formally dissolved, was literally homeless, having been ejected from its meeting rooms in what was now being called Federal Hall on Wall Street, which was being remodeled for the new Federal Congress under the direction of the French-born engineer Peter L’Enfant. (Proudly American, he no longer called himself Pierre.) Workmen were putting on a new roof, tearing out the dilapidated interior, erecting a grand, pillared balcony, and crafting a new facade in the fashionable Tuscan style. L’Enfant, remarked the French minister to the United States, Élénor-François-Élie, the Comte de Moustier, was building “a monument that can serve as an allegory for the new constitution. Both have been entirely changed by their framers, who brought their interested clients a great deal further than they had thought to go.” So impressive was the building that some suspicious members considered it to be a deliberate “trap to catch the Southern men” by inducing them to keep the seat of government in New York.

Enormous challenges confronted the men who were expected to assemble at Federal Hall. Strident opponents of the Constitution were demanding scores of amendments, or a new constitutional convention to revise the founding document. The government lacked sources of revenue, European lenders shunned American loans, and several states teetered on the brink of fiscal collapse. Settlers were pouring by the thousands into the vast territory across the Appalachians, provoking the powerful native tribes that dwelled there, and inspiring fear among the nation’s leaders that “the great Increase of New States will make so many Republics too Unwieldy to manage.”

From New Hampshire to North Carolina, aroused farmers had defied government attempts to tax them. Southerners were suspicious of northerners, westerners of easterners. Advocates of emancipation were organizing to press Congress to regulate the slave trade or even legislate an end to slavery, while the defenders of the “peculiar

The United States was a shaky assemblage of eleven sovereign states — North Carolina and Rhode Island had not yet ratified the Constitution and were still, in effect, foreign countries when Congress convened and would remain so for months to come. The nation was less a reality than it was an idea, an argument even. “Our present Confederacy is not very unlike the Monster of Nebuchadnezzar, which was composed of Brass, Clay & Iron — It is neither completely national, federal nor sovereign,” wrote William Tudor, a friend of John Adams's, in a letter to the vice president. “A Country extensive as the present united States, so differently settled, & so widely dissimilar in Manners & Ideas cannot easily be reduced to a homogeneous Body.”

As late as December 1790, North Carolina’s legislature would vote by a large margin to reject a bill that would require it to take an oath to support the Constitution. Given the primitive and unreliable communications and transportation of the day, the prospect of governing such a diverse and far-flung country was daunting. The nation extended about twelve hundred miles from south to north, from Georgia to Maine — then still a part of Massachusetts — and about five hundred miles from the Atlantic coast to the Mississippi River.

Americans mentally divided the country into four regions: the northern or, sometimes, eastern states — east of the Hudson River; the middle states of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania (and sometimes Maryland, Delaware, and even Virginia); the South, including Georgia, the Carolinas, Virginia (and sometimes Maryland and Delaware); and the West, which roughly followed the course of the Appalachians from the middle of New York State south into Georgia, and also comprised portions of the future states of Ohio and parts of today’s Upper Midwest, Virginia’s western district of Kentucky, North Carolina’s Tennessee district, and Alabama and Mississippi, both of which were claimed by Georgia.

Most Americans lived in what were essentially little more than hamlets that had been cut from the wilderness only a generation or two earlier, many of them far from any significant town. About half the country’s population of just under 3,000,000 was of English stock. Of the remainder, slaves made up about 18 percent, roughly equal to the number of recent immigrants, or children of immigrants, who were mainly from Ireland, Scotland, Wales, and Germany.

To these may be added an unknown number of Indians, perhaps as many as several hundred thousand, who were ignored by census takers and belonged to a congeries of fractured and scattered tribes including, among others, New York’s Iroquois, and the Creeks and Cherokees of western

Only Philadelphia, with 43,000 people, New York with 33,000, Boston with 18,000, Charleston with 16,000, and Baltimore with 13,000 could be considered cities in 1790, and all were dwarfed many times over by London, which had a population of almost 1 million, and by Paris, with half a million.

Americans only notionally regarded themselves as a single people. Many New Englanders thought of Pennsylvanians and their state “as opposite [to themselves] in manners and customs as light and darkness.” Representative George Clymer of Pennsylvania remarked that he had less feeling for anything going on in New York than “for the transactions in Grand Cairo. The New Yorkers and I are on an equal footing — mutual civility without a grain of good liking between us.”

Southerners were suspicious of everyone to their north: “I fear much that whoever plays the Music — the Southern States will pay the Piper,” Representative Theodorick Bland warned a fellow Virginian.

Faced with such ingrained antagonisms, Fisher Ames of Massachusetts, a passionate proponent of national unity, wished every American to “think the union so indissoluble and integral that the corn would not grow, nor the pot boil, if it should be broken.”

Meanwhile, enemies of the untried Constitution, which was meant to bind Americans more closely together, contemptuously dismissed it as “no more than general principles thrown into form,” warning that it heralded a tyranny that would soon squelch free speech and silence the press.

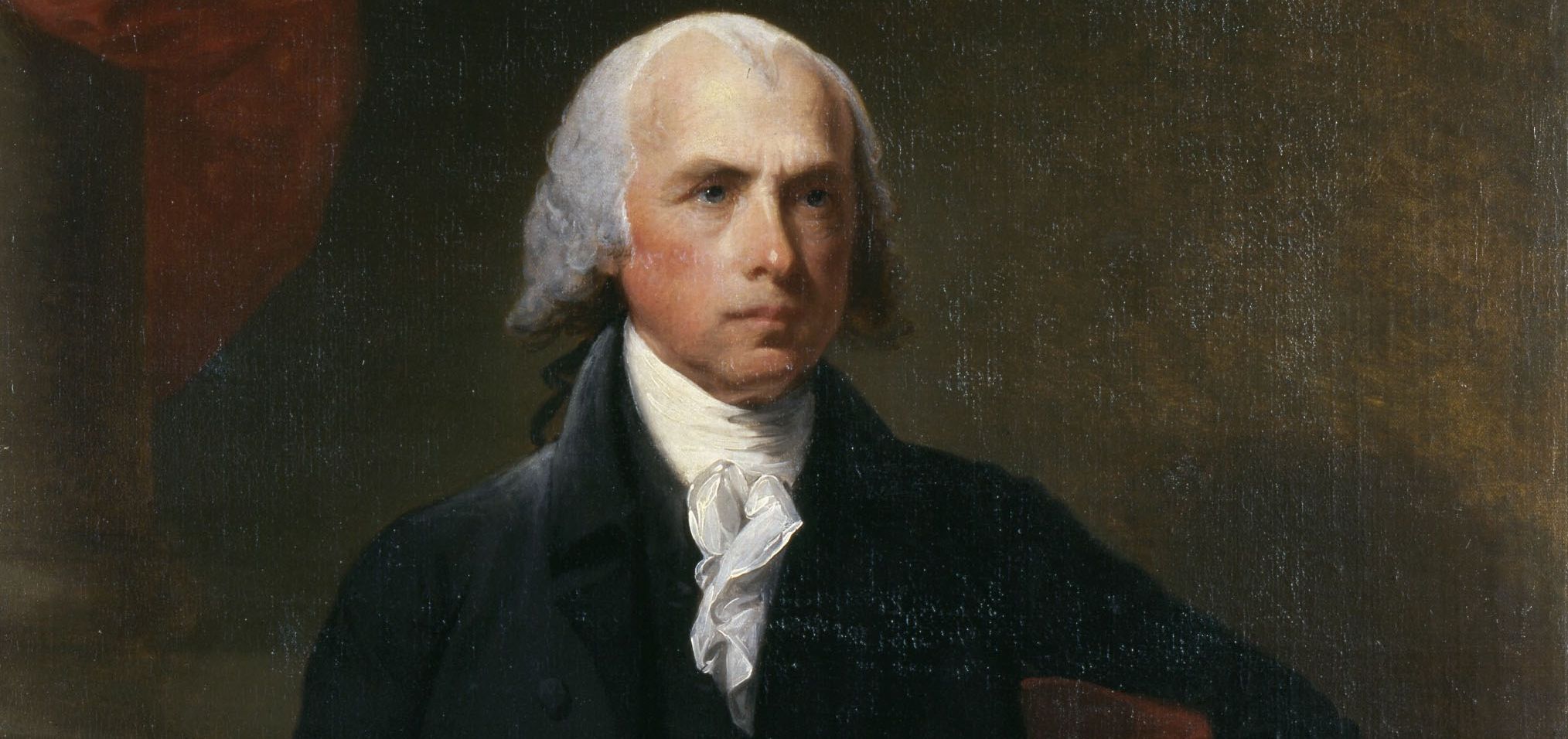

Could the new government be made to work? As James Madison, who would do more than anyone else to guide the First Congress along its path, put it, “We are in a wilderness without a single footstep to guide us.” The powerful presidency that is today taken for granted still lay far in the future. There was an elected president, George Washington, but little agreement on what his job entailed. There were no executive departments, and no federal employees except the clerks of the Senate and the House of Representatives, and Washington’s personal secretaries. Nor was there a Supreme Court, or any lower federal courts.

The nature of the relationship between the federal government and the states was pretty much anyone’s guess. Congress had no majority or minority leaders, no organized parties, no established rules of procedure. and no clear definition of the relationship between the executive and the legislative branches of government. Congressional districts varied dizzyingly in size: Representative James Jackson of Georgia represented just 16,000 people, while George Thatcher of the Maine district of Massachusetts represented more than 96,000. Slavery further skewed congressional representation.

To secure ratification of

Though rarely addressed directly, the specter of slavery would threaten to intrude upon some of the most crucial debates of the First Congress, like an asteroid hurtling toward Earth whose impact could be foreseen and was feared, but which few dared acknowledge. Under the Articles of Confederation, which the Constitution had replaced, each state had only one vote in the Confederation Congress, an arrangement that made slavery politically irrelevant, since it gave Virginia, with its 100,783 slaves, no more weight than Massachusetts, which had none.

At the Constitutional Convention, the larger states had demanded that representation reflect the size of a state’s population, raising a new dilemma: Were slaves people who should be counted, or property that should not? If only free whites were counted, the more populous North would obviously dominate the government and would eventually have the power to bring an end to slavery, if it wished. However, it was widely believed that the North would eventually lose its demographic advantage as new slave states were carved from the West. If the South could achieve sufficient leverage over the government in the short run, periodic reapportionment would eventually cement its hegemony. Counting slaves toward each state’s representation in Congress was an exquisite solution, since no one was suggesting that slaves be actually permitted to vote for the men who would “represent’ them.

If slavery was the largely unmentioned monster in the basement of the new nation, other threats could hardly be suppressed. Congress would meet in the shadow of an event that had rocked many Americans’ confidence in republican government itself. Shays’s Rebellion is almost forgotten today except as a footnote in American history. But it loomed large in the anxieties of many members of the First Congress. In the fall and winter of 1786-87, overtaxed farmers led by a war veteran named Daniel Shays shut down courts, ambushed judges, roughed up tax collectors, and invaded the homes of wealthy officials in western Massachusetts. Militiamen sent to suppress the rebels joined them by the scores. Conservatives feared that the rebels — “desperate and unprincipled men — were bent on fomenting class war and on seeking an alliance with the British.

The rebellion was finally put down by an armed force raised by wealthy Bostonians. But it revealed the hopeless weakness of the country’s military power. It also seemed to dramatically demonstrate the dangers of unmediated democracy, free assembly, and unbridled speech. In the debates to come, members of Congress would often topless a dread that America was already beginning

Reports of foreign subversion, cabals, and Indian attacks swirled everywhere around the country’s borders. Among members of the new government anxiety was widespread that the West, in particular, bound as it was to the rest of the nation only by “lax and feeble cords,” would break away and form either a separate country or ally itself with Spain or Britain. (Some Americans opposed the settlement of the west, for fear that it would depopulate the old states: “Can we retain the Western Country within the Government of the United States, and if we can, of what use will it be?” wondered the retired Revolutionary War general Rufus Putnam.)

Beyond the mountains, boundaries between whites and natives were largely undefined, animosities deep, and border warfare chronic. Settlers were begging for laws and protection, which the feeble Confederation government had failed to give. Unless they were satisfied, warned Representative Thomas Scott of Pennsylvania, “They will either throw themselves on the Spanish government, and become their subjects — or they will combine, and give themselves possession of that territory and defend themselves in it against the power of the Union.”

To the south, hundreds of Creek warriors were said to be mobilizing to attack Georgia’s frontier. General Anthony Wayne reported that the security situation there was dire, not just from Indian depredations, but also from “the insidious protection afforded by the Spaniards to our runaway Negroes ... threaten[ing] this lately flourishing State with ruin & depopulation” unless Congress acted quickly.

In the Northwest Territory, encompassing most of today’s Upper Midwest, the British not only refused to relinquish their border posts, as required by the peace treaty of 1783, but had reinforced them with eight thousand troops and were reportedly fomenting discontent among the local Indians.

Even more threatening to stability was the nation’s precarious financial condition. During the Revolutionary War, the Continental Congress had borrowed massively from European banks and governments, as well as Americans.

The government was deeply, cataclysmically, in debt, owing almost $2 million in overdue interest, with $500,000 in new payments to overseas creditors alone falling due annually. “We are in the dark,” confessed a Pennsylvania congressman. “I do believe we are now walking on the brink of a precipice that will be dangerous for us to step too fast upon.”

State debts, too, were a rat’s nest of unsupported currency and promissory notes, some of which were unredeemable even at a discount of forty to one. The face value of all outstanding national and state government debt would eventually prove to be $74 million. In 1789, no one in Congress knew what to do about this debt. “In America we had hitherto but little experience in this science [of finance],” Massachusetts representative Elbridge Gerry gloomily observed. “We are going onward blindfolded, and have seriously to

The days of the United States as a world-striding titan of trade and a manufacturing powerhouse were barely a gleam in the eye of a few far-sighted financiers. Only three banks then existed in the United States, in Philadelphia, New York, and Boston, and few corporations, and those mostly to build turnpikes. Meanwhile, at least fifty bewilderingly disparate kinds of money were in use, many of them counterfeit: Spanish doubloons and pistoles. Dutch guilders, British pounds, French guineas, and a multitude of stare-issued currencies. In 1787, the New York legislature declared all the copper currency in circulation to be officially fake. So many coins had already been clipped or trimmed for fractions of their value that even the simplest transactions often required a pair of scales.

All this monetary bedlam tortured travelers and businessmen alike. In parts of the South, receipts for tobacco often substituted for money. In some states, such as New Jersey, travelers were obliged to accept local currency that was worse than worthless everywhere else: someone who bought Jersey money in New York at a 25 percent discount, expecting to profit by it, might well suffer a further discount of 50 percent when he tried to spend it in New Jersey. This “abominable traffic,” raged a French traveler, “makes a science of deceit and teaches a man to live not by honest and useful work but by dishonest and pernicious dealings.”

Public confidence that the new government would be able to cope with all the “confusions, animosity and discord that now seems to dominate in the several States” was shaky at best. “Is there not danger from the imbecility of the national Govt.?” worried Vice President John Adams, who expected fully half the members of Congress to give up and resign within two years. “What has it to attract the hopes or excite the fears of the People? Has it power? Has it Force to protect itself or its Offices? Has it Rewards or Punishments in its power enough to allure or Alarm?”

The first Congress, particularly its first session, was dominated by the diminutive figure of James Madison, who often led the debates and overawed the House of Representatives with his unrivaled command of legislative machinery and by his powers of persuasive argument. Although he held no formal position beyond that of representative from Virginia, his intimacy with Washington and his commanding grasp of the Constitution bestowed on him a tacit authority in shaping the House’s agenda. The office of the House Speaker commanded little authority, and the positions of majority and minority leader would not come into being for generations, no one was surprised that Madison presumed to take the leading role in the House’s deliberations.

But

Roger Sherman had brokered the Constitutional Convention’s Great Compromise, which produced a Senate with equal representation for all states and a House of Representatives where representation was based on the population of the individual states. His Connecticut colleague, Senator Oliver Ellsworth, born poor but later Yale-educated, had served for years in the Continental Congress and would shape the creation of the judicial branch.

Senator Richard Henry Lee had occupied public office for 40 years, beginning with Virginia’s colonial House of Burgesses, and was regarded as one of the finest orators of the age. Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts, spartan by temperament, radical and republican by conviction, had served in public offices since 1762, signed the Declaration of Independence, and would become one of the most aggressive critics of centralized power. The philanthropic Representative Elias Boudinot of New Jersey, an evangelical Presbyterian, had spent much of his own fortune supplying the patriot army, as well as charitably providing for British prisoners of war, and later served as president of the Confederation Congress.

There were plutocrats, such as Senator Robert Morris of Pennsylvania, one of the wealthiest men in America, and agriculturalists such as Senator Ralph Izard of South Carolina, who owned five hundred slaves and forty-three hundred acres of plantation land; there were soldiers such as Representative James Jackson of Georgia, who had fought Indians on the frontier, and men of faith such as Representative Frederick Augustus Muhlenberg of Pennsylvania, who had left the Lutheran ministry to join the Continental Congress and become Speaker of Pennsylvania’s Assembly. Despite their competing interests and personalities, they would perform a feat of collaborative political creativity that has rarely been rivaled.

Political parties in the modern sense didn’t exist. But sharp differences between supporters and opponents of the Constitution had already emerged. Self-described “Federalists,” who held twenty of the twenty-two seats in the Senate, and forty-six of the fifty-nine seats in the House, were committed in differing degrees to entrenching a stronger central government. A significant minority of “Anti-federalists” — enough, one Federalist wrote, to “keep the constitution’s friends active and vigilant” — had opposed the Constitution and now sought to curtail the federal government and to preserve as much power as they could for the states.

Generally, Anti-federalists

The new system, Federal Farmer added, “was a dangerous experiment, a disaster waiting to happen,” unless states retained the power to nullify laws they deemed “injurious to the people.” One anonymous New Yorker, remarkable only in his snarling ferocity, denounced the Constitution in the New-York Daily Advertiser as nothing less than a “monarchical, aristocratical, oligarchical, tyrannical, diabolical system of slavery.” Others feared that the consolidation of powers in the presidency would make its occupant “a King as the King of Great Britain, and a King too of the worst kind — an elective King.” The only remedy, most Antifederalists held, was a massive overhaul of the Constitution.

Federalists worried that, if opponents of the Constitution succeeded in making the new government subservient to the will of the states, they would destroy the government itself. “We cannot yet consider ourselves in the Harbour of safety,” the former Revolutionary War general Benjamin Lincoln of Massachusetts warned John Adams. Most Federalists considered amendments of any kind a frivolous waste of Congress’s time, and liable, as the grammarian Noah Webster protested, to “sow the seeds of discord from New-Hampshire to Georgia.”

Others were scathing, such as an anonymous editorialist in the Freeman’s Journal, a Philadelphia newspaper, who scoffed, “The worship of the ox, the crocodile, and the cat, in ancient time, and the belief in astrology and witchcraft by more modern nations, did not prostrate the human understanding more than the numerous absurdities” proposed as amendments. An equally sarcastic writer to the New-York Daily Gazette declared, “If we must have amendments, I pray for merely amusing ones, a little frothy garnish.”

Despite all the complaints and anxieties, hopes for the new government were high, and popular interest was intense. “All eyes are looking up to Congress for the restoration of the golden age,” a constituent wrote to Elbridge Gerry. In the months that followed, lofty ambitions for sweeping legislation would collide, sometimes violently, with sectional jealousies and commercial self-interest. Personal rivalries would at times trump the public interest. Political fissures within delegations, among states, and between regions would burst their sutures. Among some, doubts about the nation’s survival would grow.

Yet the output of the first Congress was prodigious, as it transmuted the Constitution from a paper charter and a set of hopeful aspirations into the machinery of a functioning government. In its three sessions, the first two

Treaty making would be initiated through negotiations with the Indian tribes of the trans-Appalachian west, the site of the nation’s permanent capital would be decided, and the last holdouts among the thirteen original states — North Carolina and Rhode Island — would be brought into the Union, along with Vermont, setting a precedent that new states would be admitted on an equal basis with the old. “In no nation, by no Legislature, was ever so much done in so short a period for the establishment of Government, Order, public Credit and general tranquility,” John Trumbull, a Hartford lawyer not to be confused with the painter of the same name, would exuberantly write to John Adams after the third session’s close.

It would take months for the other parts of the government to take shape and bring their own political coloration to the dawn of the new system. During the first Congress, however, George Washington, so nervous that his hands shook at his inauguration, would gradually invent the presidency, stretch its powers, pry it away from the domination of Congress, and begin to define the parameters of the office for generations to come.

John Adams would woefully fail to shape the vice presidency into an assertive force in the deliberations of the Senate, condemning that office to the diminished status that it retains today. Alexander Hamilton, the first secretary of the treasury, would devise an economic system for the US government and see it enacted by a Congress almost totally unlettered in the principles of economics. Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, a latecomer to New York, would be instrumental in bringing into being the nation’s permanent capital, and—against his own visceral instincts — Hamilton’s financial plan. Henry Knox, the secretary of war, would advocate for peace with the Indians, then call for the nation’s first standing army to wage war against them. Chief Justice John Jay would set the new Supreme Court on its path.

Where would it all lead? “Here are these Americans, launched onto this great sea,” one of the Americans’ most acute and sympathetic foreign observers, the Comte de Moustier, reflected with the almost audible sigh of a world-weary Old World cynic. “These pilots, accustomed to steering small boats with some success on water seldom and little disturbed, will have another notion of the art of governing when they will have weathered the same storms and

As Congress assembled that dank and chilly spring of 1789, the world seemed new, and Americans felt in their hearts that they stood at the dawn of a new epoch. “All ranks & degrees of men seemed to be actuated by one common impulse, to fill the galleries as soon as the doors of the House of Representatives were opened for the first time,” later recalled an elderly James Kent, who as an enthralled child had watched the Congress’s first stirrings. “I considered it to be a proud & glorious day, the consummation of our wishes; & that I was looking upon an organ of popular will, just beginning to breathe the Breath of Life, & which might in some future age, much more truly than the Roman Senate, be regarded as ‘the refuge of nations.’”

The Revolutionary War period was now over. From a piece of paper, the members of the first Congress had made a government: the republican dream had been breathed into life, given political flesh and bone, pushed to its feet, and made to walk.

This was only the end of the beginning. In the next Congress, survivors of the recent elections would meet in December and shoulder their political muskets once again. New lines would be drawn, new battles fought, friends and enemies bloodied in debate. Politicians and ordinary citizens looked forward with anticipation to what was to come. They believed in politics as a tool of national survival, and indeed as the only process that would ensure the triumph of the institutions they had created, and of which they were justly proud. The right to be political was what they had fought the Revolution for, and what they had overthrown the Confederation to improve. Politics, they knew, was the engine that made the machine of republican government work and would continue to drive it, they hoped, for untold generations to come.

Some of the achievements of the first Congress were inevitably incomplete. Problems, left only half-solved or deferred would return to haunt, while some disputes were so fundamental that permanent solutions would remain elusive. Arguments over how flexibly or literally to interpret the Constitution would never end and would only grow more heated as the Supreme Court matured, states multiplied, and American society grew more complex. The deep-seated distrust of bankers and speculators that had boiled through the debates over Hamilton’s

In the Northwest, an army under Anthony Wayne would, in 1794, deliver a crushing defeat to the bellicose tribes there. Foreshadowing the systematic destruction of native peoples that was to come, the usually open-minded George Thatcher coldly reflected, "I think it must now be determined whether the Indians shall be exterminated, or the settlement of that Country be abandoned. There is no other alternative — Indians & white people cannot live in the neighborhood of each other."

The most consequential failure of the first Congress was its evasion of the corrosive problem of slavery when confronted with the Quaker petitions. Even members who loathed slavery feared that the new government could not risk an open debate on the subject without its splintering. They may have been right. But for the next seven decades this evasion encouraged southerners to bully any northern politicians who challenged slavery by threatening secession and war, as the number of enslaved Americans swelled from 323,000 in 1790 to almost 4,000,000 in 1861, and the moral problem of slavery became ever more deeply enmeshed with the politics of states’ rights. Representative Richard Bland Lee of Virginia, among others, foresaw eventual disunion as inevitable. He hoped only that it could be postponed until the South was in a stronger position. “The Southern states are too weak at present to stand by themselves,” he privately remarked in 1790. But their time would come: “I flatter myself that we shall have the power to do ourselves justice, with dissolving the bond which binds us together.”

The founders’ dream of a government without political parties was also destined to be short-lived. The Federalist consensus that triumphed in New York and Philadelphia soon eroded and was in ruins before the decade was out. Antifederalists such as Elbridge Gerry, disaffected Federalists such as William Maclay, and southern partisans of states’ rights such as Aedanus Burke would coalesce in what came to be known as the Democratic-Republican Party, which, under the leadership of Thomas Jefferson, would triumph in the presidential election of 1800, thereby giving force to the embryonic American political-party system.

By the second decade of the 19th century, the Federalists would be a spent force, a regional party with little influence and few officeholders outside the Northeast. As the Federalists withered, their opponents

But all this remained in the womb of time. As the members of the first Congress took their leave from Philadelphia in March 1791, they believed with justice that they stood in the bright, clear light of an American dawn, with the republic securely founded on enlightened principles that would endure. When Congress convened in 1789, those who imagined that it would behave like a solemn conclave of classical philosophers rather than politicians were at first disappointed. Yet, month after month, men who were at times dismissed even by their peers as “rough and rude,” “clumsy,” and “quiddling” made the Constitution work even more successfully and flexibly than many of its ardent advocates had expected, proving to skeptical Europeans, and ultimately to the world, that a republic of the people could with ingenuity and determination not only save itself from disintegration but thrive.

Every member understood that the decisions he made would shape the republic for generations to come, and that mistakes would have consequences. “Whoever considers the nature of our government with discernment will see that though obstacles and delays will frequently stand in the way of the adoption of good measures, yet when once they are adopted, they are likely to be permanent,” Alexander Hamilton presciently observed. “It will be far more difficult to undo than to do.” The process was sometimes brutal, and it certainly did not conform to the idealized version of the founding held by many modern Americans. But it worked. Time would prove Hamilton right.

Like every Congress since, the first Congress was characterized by the collision of opposing interests, ideological dogmatism, preening egos, personal and sectional distrust, self-dealing, and the dragging inertia of time-serving mediocrity. But all its members shared a common fear of failure and a determination to make government work even if it meant compromising on matters of deep principle. “I have launched my barque on the federal ocean, and will endeavor to steer her appointed course,” declared the Federalist John Vining of Delaware. “And should she arrive at her destined port with her invaluable cargo safe and unhurt, I shall not regret that in her voyage through these unexplored depths, she may have lost some small share of her rigging. Which may be considered as a cheap purchase for the safety of the whole.”

Even radical Anti-federalists resigned themselves to outcomes they had fiercely resisted. Former governor Patrick Henry of Virginia, perhaps the loudest critic of the entire constitutional system, acquiesced with relative grace. “Altho’ the Form of Governmt into which my Countrymen determined to place themselves had my Enmity, yet as we are one & all embarked, it is

Americans were rightfully proud of what their legislators had done. The prominent Connecticut lawyer John Trumbull wrote glowingly to his mentor John Adams at the close of the last session, “In no nation, by no Legislature, was ever so much done in so short a period for the establishment of Government, Order, public Credit & general tranquillity.” Even the dyspeptic Adams himself mustered a rare burst of unadulterated joy: “The National Government has succeeded beyond the expectations even of the sanguine, and is more popular, and has given more general satisfaction than I expected ever to live to see.” To a friend, Adams added, “I am happy that it has fallen to my share to do some thing towards setting the machine in motion.”

The first Congress gave new and dramatic force to the republican idea. It did not create a democracy; that would evolve only slowly over time. Nearly all the political men of the 1790s, including George Washington, still believed that government was the proper province of the wealthy and wellborn. Yet, the triumph of the first Congress was not only a victory by, or for, the governing class. Madison and his colleagues had transformed the Constitution’s parchment plan into muscular and enduring institutions that would be flexible enough to accommodate in years to come the rising power and democratic demands of Americans whose voices had been heard only distantly before in the corridors of power.

As the historian Pauline Maier aptly put it, “The Constitution’s success came less from a perfection in its design than from the sacrifices of men like Washington” and the dogged commitment of ordinary Americans “who refused to be told that the issues of their day were beyond their competence, tried to reconcile the ideals of the Revolution with the needs of the nation, and considered the impact of contemporary decisions not just on their own lives but for the future.”

Ordinary Americans had changed. Under the Confederation, Americans had rarely heard news of any sort from Congress. Public opinion now mattered. Newly emboldened newspapers brought the doings of government to the door of every citizen, including the illiterate, who gathered in urban taverns and frontier hamlets to avidly hear the latest reports read to them by their literate neighbors. Well-informed men and women alike crowded into the visitors’ gallery of the House of Representatives to listen to the debates and demanded to know why they couldn’t pack into the Senate as well.

In 1794, popular clamor would pry open the Senate’s doors to the public, too. Men who had seen themselves primarily as citizens of their individual states had now mostly come to see themselves as the common citizens of a nation and embraced their