Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Summer 2019 | Volume 64, Issue 3

Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Summer 2019 | Volume 64, Issue 3

My mother is 101 years old and in relatively good health, but has largely lost her memory. She doesn't recognize friends and family, nor understand where she is or what she's doing.

When I visit and re-introduce myself to my mother, I can't help but think of her memory loss in a broader context: our nation, like my mother in her individual case, is facing what David McCullough calls "collective amnesia." We are losing touch with the people and events who made us who we are. Like a person losing their memory, we're forgetting who our friends and adversaries are, and overlooking the lessons of past mistakes and successes.

A lot of attention has been paid to the recent surveys that show a marked decline in knowledge of American history and government. According to a recent Newsweek survey, 40% of Americans couldn’t correctly identify what countries we fought in World War II. And that was in a multiple-choice test.

Amazingly, our government officials know even less about civics than other Americans. Their average score on a recent ISI civics literacy test was 44%, compared to 49% for citizens who had not held elected office. Shockingly, 43% of officials couldn't identify correctly what the Electoral College does and 79% didn’t know the Bill of Rights prohibits establishing an official religion.

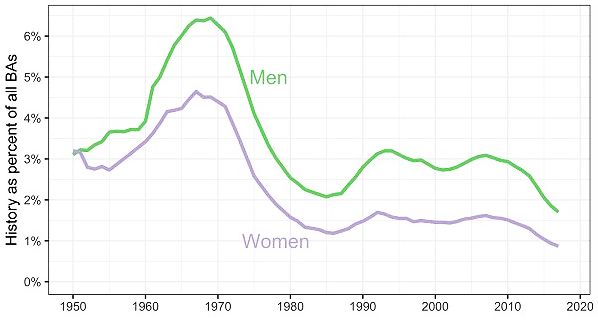

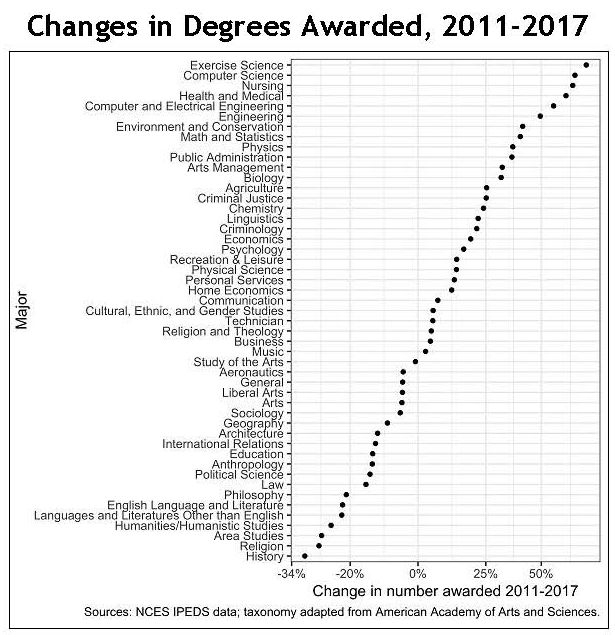

Sadly, the future of the past looks even more bleak. A recent analysis of data from the National Center for Education Statistics indicates that 10,362 fewer students earned history degrees in 2017 than in 2008.

Since the Great Recession, undergraduate majors have been shifting away from the humanities.

“Of all the fields I’ve looked at, history has fallen more than any other in the last six years,” says Benjamin Schmidt, a professor of history at Northeastern University who conducted the research. Even as overall university enrollments have grown, “history has seen its raw numbers erode heavily,” he write, especially since 2011-12.

The 2012 time frame is significant, according to Schmidt, because it’s the first period in which students who experienced the financial crisis could easily change their majors.

Why has the number of degrees fallen so rapidly? "The timing of the trend strongly suggests that students have changed their expectations of college majors in the aftermath of the economic shifts of 2008," says Benjamin Schmidt. "There seems to have been a longer-term rethinking of what majors can do for students."

Why