Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Fall 2019 - George Washington Prize Books | Volume 64, Issue 5

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Fall 2019 - George Washington Prize Books | Volume 64, Issue 5

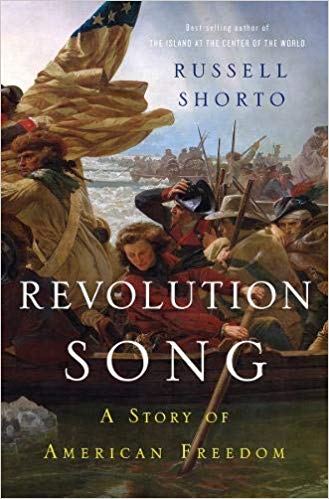

Excerpted from the George Washington Book Prize finalist Revolution Song: A Story of American Freedom, by Russell Shorto.

He was a wise man, a family man, with a kind face and soulful eyes, and he was about to kill. The people he was going to kill called themselves Americans. That word had nothing to do with him, though it would be foisted onto his identity and that of his people. He was a Seneca, a leader of the Haudenosaunee, the confederacy that the whites called the Iroquois. His name was Kayethwahkeh. Its meaning in the Seneca language had within it the idea of planting. That, coupled with the fact that corn was the most visible crop around Seneca villages, led Americans to call him Cornplanter.

Cornplanter was a young man, in the prime of life, tall, broad-shouldered, built for action. On this night, July 27, 1779, under cover of darkness, he led 120 men, armed with muskets and tomahawks, along a stream that fed into the Susquehanna River in central Pennsylvania. They surrounded a rough stockade. Inside were 21 American militiamen and about 50 women and children. At dawn one of the men in the makeshift fort appeared at the gate; the gunshot hit him with a force that knocked him back inside. Rather than accept the warning, the militiamen started shooting back. They were outnumbered and inexperienced; they had no idea what was to come. The puff and crack of musket fire filled the morning air.

Cornplanter had not wanted to be in this position: he hadn't wanted to kill Americans. But there were others who had a say, and as a political leader he understood compromise and majority rule. Earlier, at the British fort in Oswego, on the shore of Lake Ontario in Seneca country, representatives of the king of England — alien creatures in their red-and-white dress, smelling of beef and vinegar — had organized a formal council with leaders of the Iroquois confederacy, including Cornplanter. They brought out a wampum belt whose rows of colored beads signified the age-old alliance between Great Britain and the Iroquois nation. They talked about the war that was going on between their country and the American colonists, told of the majesty and might of Britain and her king, and of the inferiority of the Americans. They wanted the Iroquois to join the fight on their side. They gave presents: brass kettles, muskets with their beautifully long and cold barrels, gunpowder, sharp knives of the kind the Iroquois preferred for scalping.

The Iroquois leaders then conferred among themselves. Over the years their people had had frank business dealings and even friendships with American settlers, but settlers had also burned Iroquois villages, murdered their families and taken over their lands. The Mohawk Thayendancgea, a worldly and domineering war chief who