Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Fall 2019 - George Washington Prize Books | Volume 64, Issue 5

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Fall 2019 - George Washington Prize Books | Volume 64, Issue 5

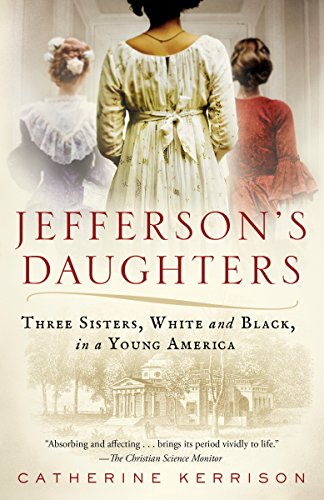

Excerpted from the George Washington Book Prize finalist Jefferson's Daughters: Three Sisters, White and Black (Ballantine Books), by Catherine Kerrison.

Jefferson had been in Paris since 1784. After his wife's premature death, Congress had asked him to represent the United States at the peace table with Great Britain, and he grasped at the appointment as a drowning man would a rope. Escaping the painful memories etched into the very landscape of his home at Monticello, Jefferson crossed the ocean to France with his twelve-year-old daughter, Martha. Three years later, Martha's younger sister, Maria, joined them, accompanied by her slave, Sally Hemings.

By that fateful summer of 1789, Paris had changed them all. Famous for his role in drafting the American Declaration of Independence, Jefferson was sought after by French revolutionary moderates who persuaded him to host meetings as they hammered out their ideas to reform their government. But Paris was also the place where he had adopted the aristocratic wigs and elegant silk suits made fashionable by the French, and where he had fallen in love with their art, architecture, furniture, and books.

Like her father, Martha took an eager interest in the political ferment. Sporting a revolutionary cockade, she was the envy of her friends when General Lafayette, riding through the streets of Paris, recognized her with a chivalrous doff of his hat. Even little Maria was changed. Initially left behind in Virginia, she had not wanted to go to Paris when Jefferson wrotc to have her join him. But once arrived, the nine-year-old became so acclimated to the beauties of Paris that she broke down in tears on their return to Virginia as she surveyed the burnt-out ruins of Norfolk, their port of arrival. Sally Hemings had learned how to care for Jefferson's silk suits and linens, as well as the fashionable clothing of his daughters. She also learned French. By this pivotal moment in French (and Jefferson family) history, then, she had learned marketable skills and had seen the possibility of a way of life that was different from the slavery she had known in Virginia.

See also, "Did Sally Hemings And Thomas Jefferson Love Each Other?"

by Annette Gordon-Reed. American Heritage Fall 2008

In the fall of 1789, however, she would agree to join Jefferson and his daughters as they boarded the Clermont, bound for Virginia. But what kind of nation awaited them? As the newly elected president, George Washington, assembled his government, he faced the challenge of transforming the political system inscribed on paper in the Constitution into a working and workable government. Chief among the questions to be resolved was who, exactly, was included in the ringing phrase "We the People" with which that document opened. In this age of revolutions, the idea of independence did not only refer to a national government, free of monarchical tics. It also meant individual self-determination. But who was