Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

December 1990 | Volume 41, Issue 8

Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

December 1990 | Volume 41, Issue 8

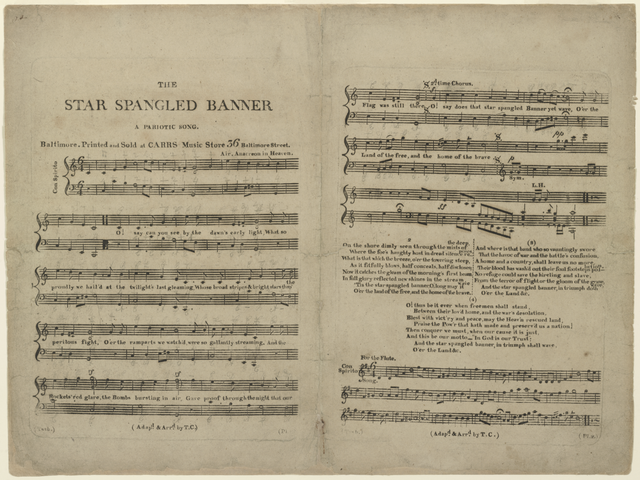

Our national anthem, “The Star-Spangled Banner,” has always been wrapped in mystery. Except for the first stanza, nobody knows the words. For historians, an even greater mystery surrounds the circumstances under which the anthem was written.

We do know that Francis Scott Key wrote it immediately after the repulse of the British fleet attacking Baltimore in the War of 1812. He had been detained while on a truce mission to the fleet and had to observe the battle with two American companions from the British anchorage eight miles down the Patapsco River.

All day September 13, 1814, Key watched the enemy squadron bombard Fort McHenry, the star-shaped brick fortification that guarded the entrance to Baltimore harbor. That night—despite a heavy rain that cut visibility to a minimum—the gun flashes and bomb bursts told him that the fort was still holding out.

Around 4:00 A.M. the firing tapered off, and soon there was only silence and the blackness of the murky night. Had the fort surrendered? Had the British quit? From Key’s flag-of-truce boat it was impossible to see anything. He could only guess.

And at this point conjecture takes over for us all. Purists say that it happened just as Key later told it: He waited breathlessly until finally, in the first light of dawn, he saw the American flag waving in the breeze, and then he knew that the fort had held out. Carried away, he began scribbling lines of celebration on the back of an old letter. “The Star-Spangled Banner” was born.

Realists wonder. The Fort McHenry flag was huge—forty-two feet by thirty feet, some four hundred yards of bunting. Flying it on a rainy night would almost certainly have broken the flagpole. At the very least it would have hung as a soggy mass, not about to wave poetically in the breeze. The fort did have a smaller “storm flag,” which it probably did fly, but it’s unlikely that it could have been seen through the smoke and rain eight miles away.

A little-known account by an English participant, discovered only in 1969, suggests what might really have happened. Midshipman Robert J. Barrett of the frigate Hebrus recalled in an account written in 1841 that as the squadron gave up its attack and started back down the river, the Americans taunted the British by raising “a most superb and splendid ensign on their battery.” According to the Hebrus ’s log, the time was about 9:00 A.M.

It seems most likely that this was the flag that Key saw. Everything fits except the time. Like any good poet, he knew that dawn is a