Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Summer 2019 | Volume 64, Issue 3

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Summer 2019 | Volume 64, Issue 3

Bruce Watson is a Contributing Editor of American Heritage and has authored several critically-acclaimed books, He writes a history blog at The Attic.

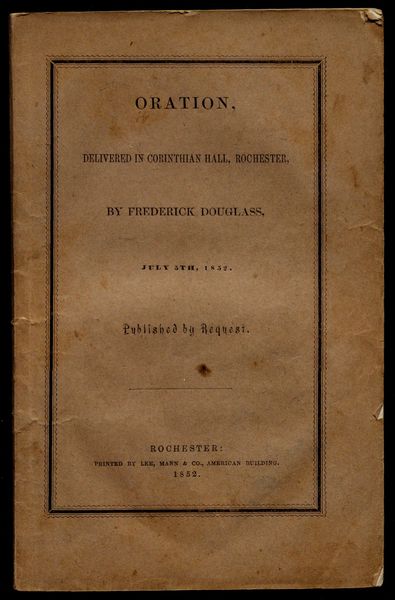

In the summer of 1852, the Fourth of July passed quietly in Rochester, New York. Thunder struck on the Fifth.

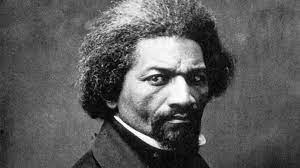

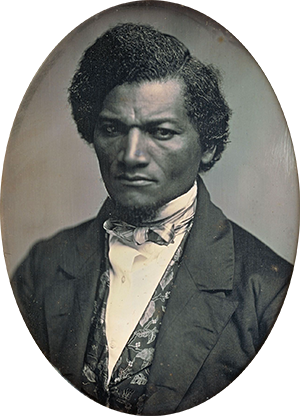

That afternoon, the Anti-slavery Society gathered in Corinthian Hall. The speaker called his talk “Oration,” and it began with praise for the city, the nation, the holiday. Then Frederick Douglass spoke truth to Independence Day.

Standing like a pillar between four Corinthian columns backing the stage, Douglass paused. “Fellow citizens, pardon me. Allow me to ask. Why am I called upon to speak here today? What have I, or those I represent, to do with your national independence?”

Many in the audience must have winced, but all knew Frederick Douglass’ story. Born into slavery. Never knew his father other than that he was white, which made Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey the child of rape. Lost his mother at age eight. Lived as a “house Negro.” Was taught to read and write — a crime in those days.

All knew how, at age 18, he had plotted his escape, been caught and flogged. All knew how, two years later, disguised as a sailor, he had walked out of a Baltimore shipyard, boarded a train, a ship, another train, and never looked back. Yet always looked back.

All knew Frederick Douglass, yet few in the audience had felt the sting of the hypocrisy he now summoned.

By 1852, four million American slaves lived as far from independence as any human could. Douglass had spoken, written, lobbied, debated. But he also lived. . .

A century before Rosa Parks, Douglass refused to give up his seat in all-white train cars and was repeatedly dragged out. A century before Brown v. Board of Education, he insisted his daughter go to public school. Gratified when one principal agreed, then shocked to learn she was being tutored in secret, he had the principal poll students. All wanted Rosetta Douglass in their class, but one parent objected. Douglass put his daughter in a private academy, but his fight continued. Rochester desegregated its schools in 1857.

At the podium between the pillars, Douglass now rose in fury. He quoted scripture. By the rivers of Babylon “they that carried us away captive, required from us a song.” But his