Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

November 1990 | Volume 41, Issue 7

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

November 1990 | Volume 41, Issue 7

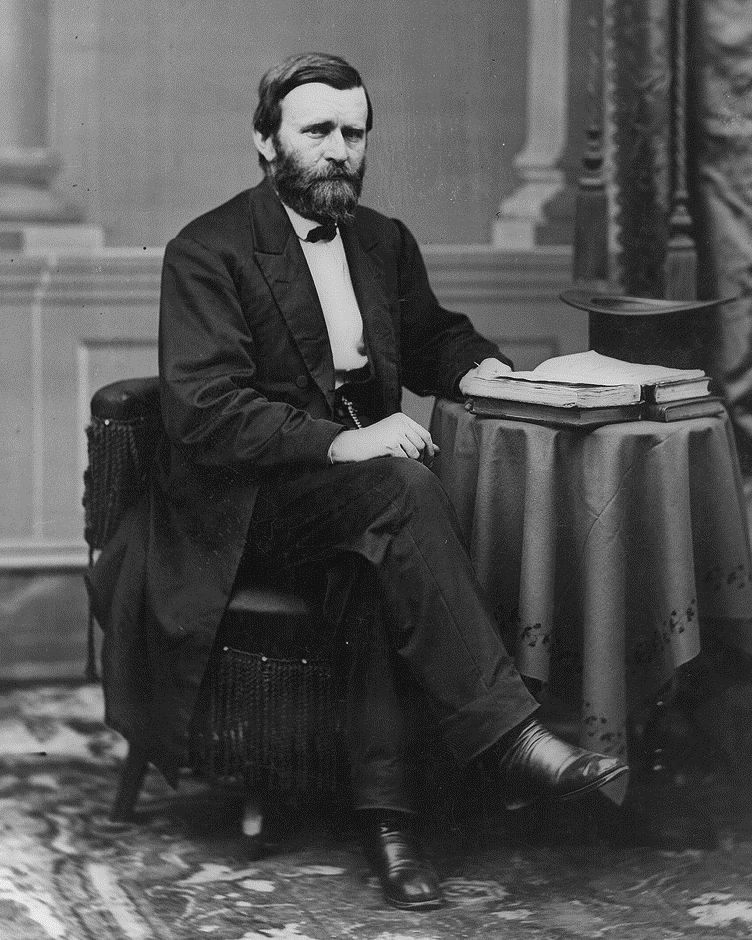

On August 8, 1885, the crowds that lined the route of Ulysses S. Grant’s funeral procession from New York’s City Hall to the vault at 122d Street and Riverside Drive numbered well over a million. “Broadway moved like a river into which many tributaries poured,” a spectator wrote. “There was one living mass choking the thoroughfare from where the dead lay in state to the grim gates at Riverside opened to receive him.”

Somewhere in that living mass stood a slender, alarmingly pale young man wearing smoked glasses to disguise himself. His name was Ferdinand Ward, and although he had been the late president’s business partner, he had no right to be there, had bribed the warden, in fact, to let him out of the Ludlow Street Jail just long enough to see the canopied hearse pass by before being locked up again to await the trial that eventually sent him to Sing Sing for grand larceny.

Ferdinand Ward was also my great-grandfather, and I’m afraid, had little, if any, redeeming social value (at least none that I’ve discovered while beginning research for a book about him). Nor was a penny of the millions he was convicted of misappropriating ever passed on to any of his embarrassed descendants.

But he did indirectly leave one extraordinary legacy to the country as a whole— Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant, recently reissued as part of the Library of America series. Without my crooked ancestor, Grant would never have written his magnificent account of the Civil War; it was only his last-ditch desire to return his bankrupt family to solvency that persuaded him to undertake the writing of it despite the throat cancer that killed him just a few days after he had finished the manuscript.

“I am reading Grant’s book with a delight I fail to find in novels,” William Dean Howells told its publisher, Mark Twain, in 1886. “I think he is one of the most natural—that is best —writers I ever read. The book merits its enormous success, simply as literature.” In our own time, John Keegan has called it “perhaps the most revelatory autobiography of high command to exist in any language.” Certainly, it is revelatory of its author. Grant wrote his memoirs precisely as he fought the war: with complete clarity and unrelenting drive and without a hint of boast or bluster.

That same year, D. Appleton & Co. got out a new edition of The Memoirs of William Tecumseh Sherman. The first edition, published in 1875, had sparked criticism from Southerners with raw memories of what Sherman had done to them and from Northern officers