Authors:

Historic Era: Era 9: Postwar United States (1945 to early 1970s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

May/June 1990 | Volume 41, Issue 4

Authors: William E. Leuchtenburg

Historic Era: Era 9: Postwar United States (1945 to early 1970s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

May/June 1990 | Volume 41, Issue 4

On an otherwise-unremarkable evening early in September 1965, when, for the fourteenth time, I was preparing lectures for the start of the fall term at Columbia University, the phone rang, and I heard an unfamiliar woman’s voice saying, “This is the White House.” I knew any number of historians for whom a call from the White House was routine. One of them, Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., had shortly before been an assistant to President Kennedy, and at the moment another, Eric Goldman, turned up for work each morning at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue as a member of the staff of President Lyndon B. Johnson. But such experiences had not been mine, and I was excited, and also a bit puzzled, until the woman added, “Stand by for Mr. Redmon.”

Unlike some of my friends in the profession, I did not walk familiarly through the corridors of power, but I had become accustomed to having in class any number of students who were destined for the public realm, or, like E. Hayes ReDmon, were already there. Among the students in my graduate courses at Columbia at about this point were Stephen J. Solarz, subsequently a congressman from New York and a high-ranking member of the House Foreign Affairs Committee; Thomas Kean, who was to become the governor of New Jersey; and Aleksandr Yakovlev, who is today Mikhail Gorbachev’s right-hand man and said to be the second-most-powerful man in the Soviet Union.

Redmon, an Annapolis graduate who had been sent to Columbia to be trained to teach at the new Air Force Academy, had, he once confided mysteriously, earlier lived in Berlin as “a spy who came in from the cold.” More than that he did not say. He was, at the time he phoned me, serving as deputy to Bill Moyers, the Special Assistant to the President who had recently been appointed Lyndon Johnson’s press chief. Redmon had been a student in my graduate lecture course, but apart from having an impression of him as a bright young man with an engaging smile, closely cropped auburn hair, and the trim appearance and erect bearing of an officer, I hardly knew him. Once before, he had phoned to ask about an FDR reference for a Johnson speech, and I assumed when I heard he was the source of this call that he simply wanted another piece of information.

In fact, he had a great deal more in mind. He had been talking to Moyers about the historic importance of the first session of the Eighty-ninth Congress, now drawing to a close, and about the possibility of my writing an analysis of it from a historian’s perspective. The administration had been working on the

I was delighted, and for more than one reason. Ever since 1938, when Congress had enacted FDR’s proposal for a wages-and-hours law, liberal reform in America had been stymied by a bipartisan conservative coalition. Harry Truman had not been able to get through his Fair Deal, and at the time of his death in November 1963 John F. Kennedy’s New Frontier was foundering. It had become commonplace in the early sixties to grouse about, in the words of James MacGregor Burns’s book of the same title, “the deadlock of democracy.” But in 1964 under Lyndon Johnson the stalemate ended as Congress passed a strong civil rights bill, a tax-cut measure, and the rudiments of LBJ’s war on poverty. In 1965 new laws came thick and fast—federal aid to education, voting rights, Medicare, Medicaid, a new cabinet department (Housing and Urban Development), the Twenty-fifth Amendment (presidential disability)—and more, including a highway-beautification bill favored by Lady Bird Johnson, were nearing passage.

I wanted to understand, both as a writer on contemporary history and as someone who worked in the civil rights movement as well as for the national liberal organization Americans for Democratic Action (ADA), how this breakthrough had occurred. But there was an even more compelling reason. 1 had never spoken to a President at the White House, and I was eager for the opportunity to meet the incumbent of an office that ever since grade school civics lessons I had been taught to respect.

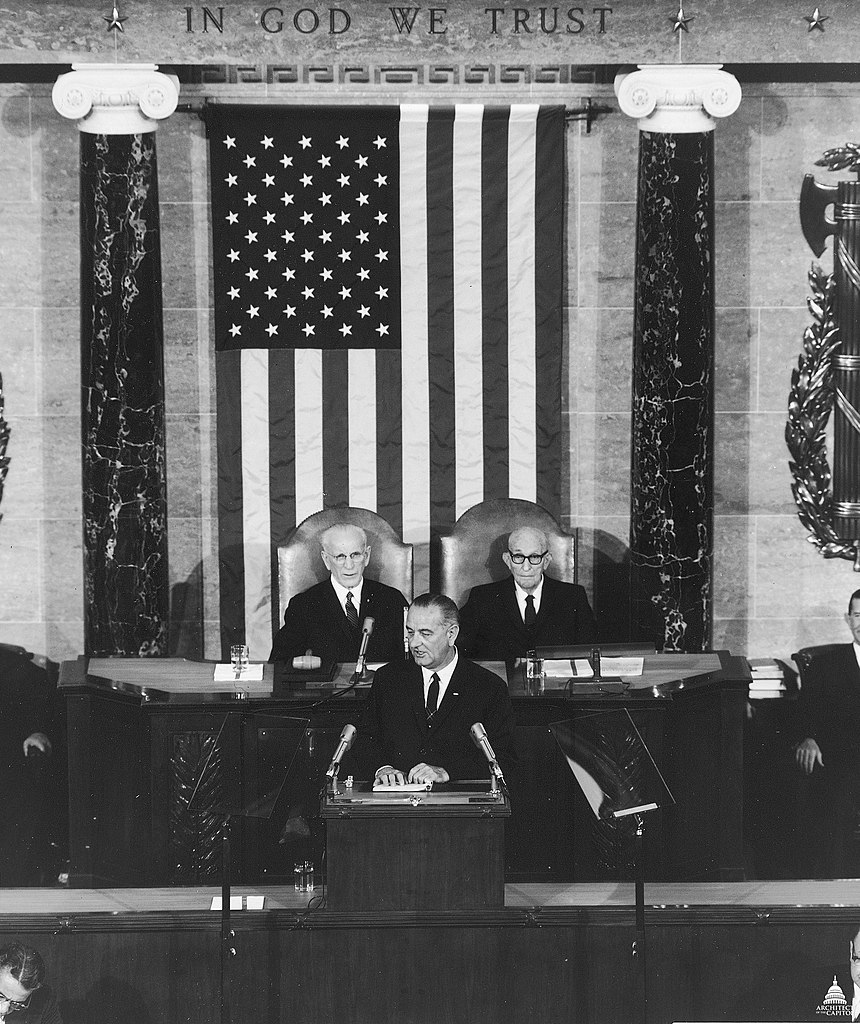

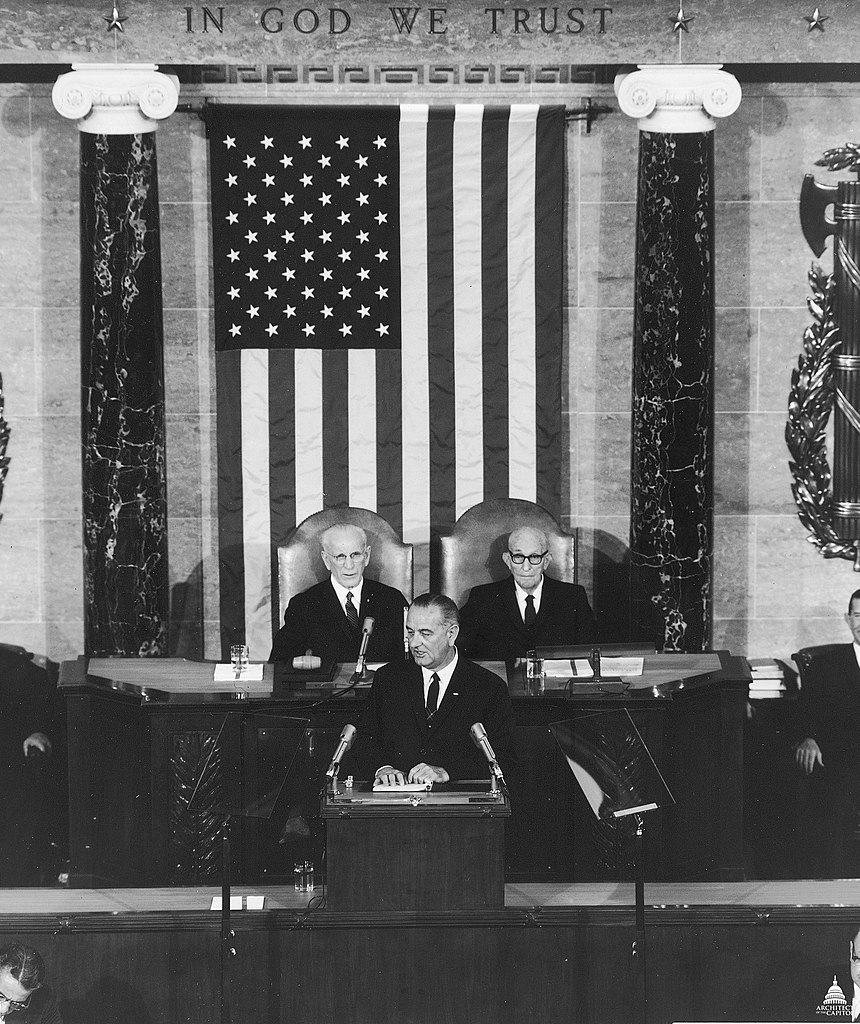

As we talked about the proposal on the phone, thoughts for two articles emerged. One would be a piece on the origins of the Great Society, especially the work of the task forces of intellectuals and social activists that had been set up to advise Johnson. The other would be a study of the President as chief legislator. I told Redmon that I had just attended a convention of the American Political Science Association at which I thought speakers underestimated not only the originality of some of the Great Society but also Johnson’s contribution to getting the program enacted. They assumed that the great spate of laws could be wholly explained by the 1964 election, which had so greatly swelled the Democratic margin in Congress, but Franklin Roosevelt had enjoyed an even bigger advantage in 1937 and had not achieved nearly so much that year. The country, I firmly believed, did not properly appreciate Lyndon Johnson.

Though our conversation ended on a cheery note, I realized that a lot still had to happen before the plan could become a reality. Redmon told

On September 22 I experienced a Walter Mitty day as uniformed officers waved me past the White House guard post and a sleek black limousine whisked me out of the White House gates up to Capitol Hill and down again. I spent the first four or five hours in highly instructive interviews with Douglass Cater, the articulate, soft-spoken architect of LBJ’s federal aid-to-education program; with the two men who were Johnson’s liaisons with the Senate and the House; and, following lunch with Redmon in the White House mess, with the Treasury’s head of congressional relations.

It was not until I reached Capitol Hill in mid-afternoon, though, that I fully sensed the excitement the Great Society was arousing, the biggest stir since the halcyon days of the New Deal. In the House I had the good luck to run into two AFL-CIO lobbyists I knew (one of them the former congressman Andrew Biemiller), and in the midst of their busy rounds to push a revised minimum-wage bill, they stopped briefly to fill me in on what labor thought of Johnson’s achievements, then raced on. As I took in the frantic pace (Speaker John McCormack went scurrying past me), I realized why the House majority leader, Carl Albert, could not see me until that weekend.

The United States Senate, which I moved on to next, seemed to be even more engrossed in the President’s agenda. A glance at the Senate floor revealed a vigorous debate with some familiar figures taking part (at one point Eugene McCarthy hurried by), but promptly at four o’clock, when the White House had scheduled an appointment for me, the Senate majority leader, Mike Mansfield, walked off the floor, greeted me pleasantly, and took me to his comfortable office, where he made me a cup of coffee and, with the easy grace of a man who had himself been a professor of history and understood my mission, conversed about the Great Society. “Johnson has outstripped Roosevelt, no doubt about that,” he said. “He has done more than FDR ever did or ever thought of doing.”

After some twenty minutes an aide came in to tell the majority

The aide whispered, “The Kennedys and—” (I did not hear the rest).

The majority leader said a hasty good-bye and walked out onto the floor, and I was chauffeured down Pennsylvania Avenue for yet another engagement, this time with Lawrence O’Brien, an honest-faced Irishman from Massachusetts who had been appointed as Postmaster General. As he filled me in on the details of the congressional liaison operation he had been heading since the Kennedy era, the phone rang, and he repeated the message he had just been given: “Seventy-six to eighteen.” Instantly he relayed the news over the intercom: “Is he there? . . . Seventy-six to eighteen. Forward it.” I had no doubt from what I had seen that afternoon what those cryptic numbers meant—still another victory in the Senate for LBJ: enactment of the historic immigration-reform legislation ending racist quotas.

At a little before five-thirty, Hayes Redmon came in to break off my discussion with O’Brien upstairs in the White House and take me down to be ready for the President. We waited what seemed interminably in a lovely room with a Remington over the fireplace, a Whistler, a French impressionist, the room brightly painted and suffused with light. Nearly thirty minutes went by, and to the last I feared that Johnson would not be able to see me, since this was the day the India-Pakistan crisis over Kashmir was peaking. The President had had a long phone talk with the Pakistani leader Muhammad Ayub Khan that very morning. But a buzzer rang, an aide came in to announce that the President was on his way, and some minutes later the aide reappeared to say we should go in. It was now a little after six. I crossed a corridor to a small office, and there was the President.

He had his back toward me when I first saw him, giving me a chance to get an impression of him unobserved, and he struck me as much more imposing than I had imagined—not only very tall but burly. He carried more than two hundred pounds on his six-foot-four-inch frame, but he appeared to be even bigger. The New York Times reported that “Lyndon Johnson seems 20 feet tall—when he really measures no more than 10,” and his former press officer George Reedy has written: “By sheer size alone he would dominate any landscape. And no one could avoid the feeling of an elemental force at work when in his presence. One did not know whether he was an earthquake, a volcano, or a hurricane but one knew that he possessed the force of all three combined and that whatever it was, it might go off any moment.”

I sensed immediately that something was wrong. Instead of

Johnson favored this retreat, where Truman and Eisenhower used to nap, for secret meetings and informal exchanges. It was intimate (the President was never more than a foot or two from me) without being really congenial. The furniture, green and overstuffed in an odd combination of modern and Victorian, included an Eames chair upholstered in velour of the same bilious green that colored most of the rest of the room. When we first entered, Johnson sat next to me and Redmon on a couch so that our picture could be taken by the President’s favorite photographer, Yoichi Okamoto. Then he went over to the Eames chair, and for the rest of the evening we sat across from each other; farther down the couch was Redmon, and farther still, in a chair on the other side of the room, Doug Cater.

The interview could not have gotten off to a worse start. As I awaited the President’s signal to ask the first question, Redmon broke in to say with a smile, “Tell him what Mike Mansfield said to you.” Flustered by this unexpected request, I flipped through the pages of my yellow pad in an unavailing effort to find my notes.

Johnson, exasperated with being confronted at the end of a taxing day with a ham-handed professor, said curtly, “I’m going to have to run soon. You’d better ask me what you want to know.” Clearly this was going to be a brief interview.

Picking up on his cue, I managed to start on my first question: “Mr. President, this has been a remarkable Congress. It is even arguable whether this isn’t the most significant Congress ever.” I thought of this opening as a way of being ingratiating since I had some doubt whether this Congress really was as important as those early in the New Deal, but before I could add one more sentence to frame a question, Johnson interjected, “No, it isn’t. It’s not arguable.” I grinned, then realized he was dead serious—even a little angry. It was my first indication that he believed his accomplishments were the most important in all our history. “Not if you can read,” he snapped.

“You can perform a great service,” the President continued, “if you say that never before have the three

I had no way of knowing then what studies of the President have since revealed: that this way of acting had a long history. One of LBJ’s college boardinghouse associates has recalled: “He was very entertaining sometimes. . . . But if someone else tried to talk—well, he just wouldn’t let them. He’d just interrupt you—my God, his voice would just ride over you until you stopped. He monopolized the conversation from the time he came in to the time he left. I can still see him reaching and talking, reaching and talking.” Similarly, John Kenneth Galbraith remembers an episode when Johnson was Senate majority leader: “He got Arthur [Schlesinger] down to his office—spent a whole mornning with him. . . . Johnson went over every member of the Senate—his drinking habits, his sex habits, his intellectual capacity, reliability, how you manage him. Arthur said, ‘Most informative morning I ever spent. Never got a word in edge-wise.’ Not very long afterwards, Johnson . . . said, ’I’ve been meeting with your friend, Arthur Schlesinger. Really had a very good meeting. We had a long talk. He’s a right smart fellow. But, damn fellow talks too much.’”

Johnson, having raised his own rhetorical question, promptly offered a lengthy response. “First, there is the quality of leadership in each of the branches. I’ll put the executive branch last. First, you have to take the pioneering, courageous, compassionate leadership of the Supreme Court—its decisions on Social Security, on AAA, on public power (the Duke Power case), the Brown decision.” I was struck by how readily he reached for examples from the 1930s, when he had been a New Deal zealot; “AAA” referred to the Agricultural Adjustment Act, FDR’s farm program. The President still seemed to be living in part in the age of Roosevelt.

He went on: “It has shown great leadership, compassion, foresight, courage. It has been given direction by men like Warren who came out of the West with a record as a prudent progressive, balanced by men like [Hugo] Black, out of the South, with a populist background—the people come first—and [Tom] Clark and Felix Frankfurter. So the Court did a lot of pioneering. Look at a decision like the Gideon case. I don’t think ever has a court been led by more balanced, judicious temperaments. Here are men who have sat in the Senate, in courts, who have a background of a lot of experiences.” (He pronounced the word court as “coat,” then caught

The President seemed tired, distracted, as any man might be when called on to make conversation at day’s end with someone he did not know, but maybe with something else bothering him too. At the outset he had said he was thirsty and wanted a Coke. He asked if I’d like one, and when I said I did, he ordered a Coke for me, something else for Redmon and Cater, and a grape soda for himself. (Though he was known to be fond of Cutty Sark, his real addiction was to low-calorie soft drinks.) As he sprawled in his chair, sipping the soda pop, sniffing at an inhaler, looking white-faced, bone-weary, rather severe behind thick-rimmed glasses, he listlessly pushed the words out.

“Then there’s the Congress,” he continued. “There’s a geographical balance—leaders from Montana and Illinois [meaning Mansfield and Everett Dirksen]. And in the House, Oklahoma’s Albert, a Rhodes scholar, and McCormack from Massachusetts.” He boasted: “I came to Washington in 1928. Of the 435 men in the House, only six were there when I first came here—McCormack, (Joseph) Martin, [Emanuel] Celler, [Wright] Patman, Howard Smith.” He did not name the sixth. In fact there were only five, and his comment exposed his streak of grandiosity when he remembered the past. Johnson was still in school in 1928. He did not go to Washington until late in 1931, when he got a job on a Texas congressman’s staff. He was not himself elected to Congress, contrary to the implications of his statement, until 1937.

“McCormack knows the system,” he maintained. “He knows how to cooperate. At the same time,” the President remarked, smiling so broadly it was more like a smirk, “he knows how to protect his perquisites. He can cooperate, but he has no ring in his nose.” (Off the record, though, the White House staff told me that Johnson actually thought McCormack was a spent man who failed to advance the Great Society program with enough energy.)

“For years, little got done,” he carried on, still speaking as though reciting a twice-told tale. “These ADA liberals like Hayes and Doug, they jerked, they talked. They were like the local bully in front of the barbershop talking of making a million and never getting it. Not since 1938, 1937, had much got passed.” Those sentences about the quarter-century of deadlock appeared to be leading him toward a paean of praise for Congress, but instead they reminded him who it was who had ended the stalemate.

“And now the executive branch,” he persevered. “Take the cabinet—it had gone through the Bay of Pigs. It had had its washouts. We plugged the holes.” 1 was startled by these words, which implied that he was deliberately comparing himself with John F. Kennedy and denigrating him and those around him, but before I had a chance to take

That sentence got him going on what turned out to be his favorite topic: himself. “Never was anyone so well trained for this office,” he began. “I met with the President every night for twelve years.” (That was another claim that was palpably untrue.) “I worked out schedules. I was unofficial leader. I headed the Armed Services Committee. They never made a move I wasn’t in on. I created the preparedness subcommittee. I became whip. I became minority leader. I became majority leader. I led by one seat. [That is, the Democrats had a one-seat margin, barely enough to organize the Senate.] I had every Democrat in his seat and voting together to censure McCarthy. Except for Kennedy, who was ill; he wouldn’t give us his pair.” (The animus against JFK was becoming more and more apparent.)

Franklin Roosevelt seemed an even less likely target, for the one quotation most associated with Johnson was his saying in 1945 on learning of FDR’s death, “He was like a daddy to me always.” Ever since, he had been, in his public statements about the President who had fostered his career, the very model of filial piety. Now, however, he declared: “In 1936 Roosevelt won by a landslide. But he was like the fellow who cut cordwood and sold it all at Christmas and then spent it all on firecrackers. It all went up with a bang. He did get things done. There was regulation of business, but that was unimportant. Social Security and the Wagner Act were all that really amounted to much, and none of it compares to my education act.” (Parenthetically he interposed, “We’ve added enough to the public domain to make Teddy Roosevelt ashamed of himself.")

“We have cut down the fear that destroyed Franklin Roosevelt,” he asserted. “The President has terrible power. People are fearful of the President’s power. That fear brought this Republic into being. When people did not like what Roosevelt was doing, he called them economic royalists and moneychangers. He said they had met their match and would meet their master.” Johnson’s voice rose, and he eyed me directly. “It was like people fighting and spitting at one another.”

Johnson saw himself, unlike his renowned predecessor, as the maestro of consensus. “We created a bridge with the people,” he bragged. “We got the titans of industry and labor, and we

“Congress is not afraid. I revere ‘em. I am not for denouncing Congress all the time. I am not like Schlesinger and you writers who think of congressmen as archaic buffoons with tobacco drool running down their shirts. I revere Congress. I got up at seven this morning to have breakfast with them. I don’t have contempt for them.” He added: “I gave the Supreme Court a dinner, and I revere ‘em. I don’t want to impeach Earl Warren.”

The reference to Schlesinger is suggestive. Eric Goldman has reflected on “the mounting irritation of the President and of [his chief aide Walter] Jenkins against Schlesinger. There was something about my fellow historian, to his glory or demerit, which peculiarly roused the Johnsonian.” Schlesinger was perceived as the quintessential Kennedy man who could not stomach having the aggressively coarse Texan in the elegant patrician’s chair. Yet he also believed that Schlesinger could determine his place in history. On the day after Kennedy was assassinated, he told the chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers, Walter Heller: “Now I wanted to say something about all this talk that I’m a conservative who is likely to go back to the Eisenhower ways or give in to the economy bloc in Congress. It’s not so, and I want you to tell your friends—Arthur Schlesinger, Galbraith and other liberals—that it is not so. . . . If you looked at my record, you would know that I am a Roosevelt New Dealer. As a matter of fact, to tell the truth, John F. Kennedy was a little too conservative to suit my taste.” (Among the many conceivable explanations for why Johnson was so testy with me was that he had been briefed that, like Schlesinger, I was a New Deal historian. We both came, too, from Ivy League universities, toward which Johnson bore an enduring grudge; he was sure that no matter what he did, that crowd would never accept him.)

The mention of Schlesinger may have started him thinking of Kennedy again, for abruptly he switched topics. He said, his voice turning mean: “No man knew less about Congress than John Kennedy. He never even knew enough to know how to get recognized. When he was young, he was always off to Boston or Florida for long weekends. I never saw him in the cloakroom once. I never saw him eating with another congressman once. [Speaker Sam] Rayburn never knew him. The only

Nearly half an hour had gone by, and to my surprise, Johnson still showed no sign of terminating the interview. I knew from my work on FDR that if you were granted twenty minutes with a President, you could count yourself very fortunate. Indeed, earlier that day, I later learned, the minister of state for external affairs of Nigeria had been cut off after eighteen minutes, Prince Mikasa (Hirohito's brother) of Japan and his family after fourteen minutes, and a Texas state senator after two minutes. But Johnson plowed straight ahead.

I had not noticed during this time when the President never stopped talking that the room had three television consoles, for they were blank as he spoke, but at six-thirty Johnson snapped on the TV sets with a remote-control device that enabled him, while scrutinizing all three at once, to switch the sound from channel to channel. He first watched David Brinkley on NBC reviewing the India-Pakistan situation, and as the network focused on the UN, he peered intently at his ambassador, Arthur Goldberg, on the screen. When an Indian spoke, the President broke his brief silence to say: “I met with 93 leaders of foreign nations. I gave them the model of what we wanted.” He stopped precipitately when he observed that the ABC screen was on Vietnam, turned up the sound briefly, then went back to NBC for interviews with Mike Mansfield and a Pakistani. For most of the next hour the sound was on very loud. At times the President listened; at other times he spoke against it, for the TV only diverted him spasmodically from his talkathon.

“So we had a base,” he recapitulated. But he could not build on that summary because he was riveted to the TV.

On CBS a congressman was explaining the compromise on home rule for the District of Columbia, and that may have prompted LBJ to return to his main theme. “This isn’t just the Eighty-ninth Congress,” he recommenced. “We started out on November 23, 1963. There’s really three things contributed to what the country has done. I won’t say what I have done.” Brinkley was now reporting on U.S. casualties in Vietnam, but that did not disrupt his soliloquy. “First, confidence in the country on

At this point the phone rang, and the President spoke in a very low voice for perhaps six or seven minutes. I could hear only snatches, the word 1962 repeated, and one sentence, “Have you ever found who represents them here?” As he murmured on the phone, the TV continued to blare, “Of course Nytol is safe,” and to sing the praises of Dristan. I scanned the pictures in the room—photographs of the last five Presidents, starting with Hoover and including one of FDR shaking hands with a boyish-looking LBJ. (Only many years later, when I got hold of the White House daily diary for that day, did I discover who his caller was—Abe Portas, Johnson’s fixer extraordinary and later his aborted choice to be Chief Justice of the United States. But I still do not know what their conversation was about.)

No sooner had the President hung up the phone than he picked up the thread of what he had been saying to me despite the lapse of time. “We could be progressive without being wastrels,” he resumed. (He stopped for a moment as Brinkley mentioned the drafting of doctors and dentists.) “We put in a cost-conscious program. We saved three and a half billion on defense and put it on liberal projects.” As he spoke, he switched to ABC to hear Bill Lawrence report on the President’s role in the Kashmir dispute, but the channel hopping did not halt the flow of words, especially since he was back to talking about himself. “We knew what we wanted to do and how to do it,” he said proudly. “I was like the jet pilot who has flown a plane a thousand times across the Atlantic. After all those times I’d know how to close the door of a plane and open the throttle. You couldn’t do it. But then I couldn’t do what you can do—write. You find it easy to sit down at a typewriter, and you know where the subject and predicate are.”

NBC now featured an account by Nancy Dickerson of Luci Johnson’s first days in college. The President got out of his chair to dim the lights to get a better look at her. All conversation stopped as Johnson gazed intently at his daughter. I later had a nice encounter with her in Austin, where she impressed me as being good-hearted and

At this point he interrupted himself once more to lash out at the press. “We had a few people around town cutting at us,” he sneered, his voice suddenly bitter, his lip thrust out. “When I came on as President, the Times said the one thing sure to happen is that we would have a closer election in 1964. If the livelihood of The New York Times depended on its accuracy, they would be shot at sunrise. When we went to Texas in November 1963, Kennedy and I were running 50-50 against the Republicans generally and against Goldwater as the likely candidate, 52-48.” His voice was now very loud and resentful, as he instructed me, “Look at the kinds of things the Evanses and Pearsons say,” alluding to the syndicated columnists Rowland Evans and Drew Pearson. He gestured toward Redmon: “Get him the Busby memo on all the things these fellows said wrong, the memo prepared for Holmes Alexander.”

Thought of the press had him fuming, to such an extent that he had a hard time concentrating on his presentation. He made an effort to keep going on the task forces, but without getting rid of a nasty element in his voice. “So we had thinkers,” he continued. “Some ran and talked to the press and got famous. So we had to scrap them. Others did their jobs faithfully, and we got bills.” These bills were enacted, he asserted, because the nation favored them. “We’ve kept the people with us, so we’ve gone from 61 percent to 69 percent. And in New York last week it was 78. No one’s had this before.”

The press, though, had gotten his goat, and he returned to his attack on “these superficial, shaller [shallow] columnists.” He added, as if communicating less to me than to himself: “But they don’t have much influence anywhere. I’ve started keeping record. If there are five lies in a newspaper, I write them. One day last week the Washington Post had eleven lies. They talk about ‘well-informed sources.’ That just means what they want to say. Someday we’ll have to pass a law stopping them from using ‘well informed.'” He hammered out that sentence as

Having gotten riled up against the press, Johnson turned to vent his wrath on the Republicans in Congress. He said with a peculiar smile, as if getting pleasure from letting me in on a sneaky trick people were playing that he well knew they were playing: “The Republicans don’t vote against a bill. They vote to recommit . But that means killing it. Then on the final vote they all turn around and vote for it. Ford keeps shifting from a vote to recommit to voting for it on the final roll call.” (The House minority leader, Gerald Ford, appeared to be a particularly irritating thorn in his side, for the White House staff later sent me a memo showing that Ford got four percentage points better support from the Republican members of the House than Johnson received from the Democrats.)

To my disbelief, my watch showed that we had passed the seven o’clock hour with still no indication I was expected to leave. At the stroke of the hour he switched to CBS for Walter Cronkite and Eric Sevareid, but he bellowed against the TV as if to drown them out, while in his most imperious manner preening himself on his success with Congress. “This year a hundred bills will become law,” he exulted. “Any other session, the maximum is twenty.” He added: “The Executive ought to lead. I believe that. I propose; they dispose. I’ve been up on the Hill more than any other President, and more of them have been here. Every member, 535 of them, has been here for two complete briefings. The least congressman from the most remote district can ask whatever he wants of the President.” It appeared that he was overwhelming Congress as he was overwhelming the evening news, and as his harangue, now more than an hour long, continued with no evidence it would ever cease, he was overwhelming me too.

I later read much about how Johnson pulverized those around him, and though he did not chew me out as he did his staff, his manner was so domineering that I felt diminished. Sometime later another interviewer, the feisty Texan Ronnie Dugger, wrote of Lyndon Johnson: “Leading you through the White House as if he owned it, which for his time he did, he cuffed you with his rough anger. He occupied his rocking chair with an indifferent authority, as if, should it squeak, he would maul it. There was threat, ferocity, real danger in him.”

At that juncture, to my surprise, a newcomer walked into the room, and the President got up to introduce me to the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare, John Gardner. But Gardner, smiling familiarly,

Gardner’s arrival surely meant I must go, so that the President could confer with his cabinet officer; but Johnson showed no intention of having his monologue abbreviated, and Gardner, a handsome man at ease with himself, sat there a captive listener, attentive but mum as the torrent of words continued. “Thus there’s been leadership,” the President reiterated, recollecting precisely what he had been saying as Gardner walked in. He was about to elaborate on this theme when for the first time since the screen flashed Luci’s image he got completely caught up in the evening news. CBS was showing U.S. Marines giving medical aid to the Vietnamese. Excitedly the President rose in his chair, flailing his arms, and yelled: “I wish you would call over there and tell them they’re doing a good job. Tell McNamara. I like to see Marines doing something besides killing: helping palsy.” Until then I had been disconcerted by the President’s cold-blooded absorption with power. This was the first time he had displayed any real warmth, any indication he wanted to use power for humane ends—though he showed no awareness of how bizarre was the conjunction of “killing” and “helping palsy.” He contemplated with genuine concern the TV images of a Vietnamese child with muscular dystrophy, doomed to die. There was a slight tic in his cheek as he stared.

This mood changed, though, when CBS turned its attention to a demonstration in Manhattan against the government’s Vietnam policy, with a counterdemonstration of pickets screaming that the protesters were disloyal. No longer could the President comfort himself with the thought that the American presence in Southeast Asia was a health mission, and he found another target for his fury. Animatedly he said to me: “One of the most difficult things I have to do is to read letters from our soldiers in Vietnam saying, ‘We don’t mind dying, but we hate not to be appreciated, and we hate to see these guys on the campuses attacking what we are doing.’”

Johnson seemed prepared to go on further in this vein, but as he was speaking, another newcomer entered the miniature hideaway, which was starting to look like the crowded stateroom in the Marx Brothers movie A Night at the Opera . Suddenly into the room, again altogether unexpectedly, burst Lady Bird, back from a trip to the Midwest to promote the administration’s beautification measure. She was dressed chiefly in blue and was very attractive, radiant, unmistakably in high spirits. She came up to the President as he rose

Johnson had now been lecturing, relentlessly, for an hour and twenty minutes, and either the strain of that effort or the thought of Democrats’ abusing his wife triggered a new explosion. For a moment he remembered what he had been arguing and tried to keep going. “So we’ve been holding these meetings,” he said. But swiftly his countenance darkened, and he muttered resentfully, “Just because this Republican couldn’t get what he wanted, he says I’m applying pressure. [William] Cramer. Florida. I wouldn’t waste time on him.” He continued: “That kind of attacking’s not going to get them anywhere. A party’s going to be successful if it builds a better mousetrap. If the other man says, ’I’ll educate your kids better, I’ll build better houses, give you more pretty parks,’ only then can he beat us out.” That sounded more reasonable, but Johnson could not free himself from a consuming egocentricity. “I passed one bill yesterday, 378-0,” he boasted.

Though these remarks were ungratifyingly disjointed, they created enough space to give me a chance, after all this time, to open a second line of inquiry. “Mr. President, people have been telling me today that this Congress is going to be so successful that at the end of the next session, the cupboard will be bare,” I ventured.

“No,” he replied, “the twentieth century has too many problems for that.” He expounded: “Next year will be a year of administration. There won’t be as many new laws. I have got to go out and see the folks and see whether they are against more education, whether they are against parks, whether they are against . . .” and he listed several other items. “I don’t think they are. Even the Republicans are voting for them.”

My comment had diverted him from his rancor enough that for a few moments he calmed down; but the word Republican set him off again, and in the closing minutes he came close to losing all control of himself. “They all said that I was going to destroy the UN, just because I wouldn’t go to San Francisco

Once again, I could not believe what I was hearing. I had, of course, heard such language before, but I did not expect to, or want to, hear it from the President of the United States. Furthermore, it seemed incredible that in talking to an utter stranger, let alone someone who was writing an article about him, he would be so indiscreet. Did the President not know I was taking all this down? Yes, he did. In fact, at one point he looked right at me, as though waking himself from a self-induced trance, and said, after I’d been scribbling rapidly for quite some time, “You go ahead and take notes if you want.”

By seven-thirty, the interview had been going for almost an hour and a half, and we began stirring to leave. Even when we stood up, though, Johnson went on talking for a few minutes more, particularly about the dinner meetings he had been holding at which businessmen drew numbers for a chance to speak. We walked together into the outer office, the President grasping me by the arm. I managed a good-bye and a thank-you and departed, profoundly disquieted by what I had just seen and heard. The President had been comparing himself with others, past and present, and finding no peer. I was reminded of something Barry Goldwater had said: that LBJ had so much power the Democrats could plug him in.

In the mercifully brightly lit press office afterward, I said to Hayes Redmon, “You don’t have to tell me I can’t use ninety percent of this now.”

“Better make it 95 percent,” he answered. “Especially about Kennedy.”

Though the White House had no control over what I might ultimately do with my notes, I could not quote directly without permission so long as Johnson was in the White House. 1 did piece together an article from the other interviews I had conducted that day, from subsequent sessions with Bill Moyers, Richard Goodwin, Carl Albert, and the Council of Economic Advisers, and from materials such as minutes of cabinet meetings Moyers had sent to me; published in The Reporter,

I have come to hold a different view of the outcome, for if I had been able to publish my essay that fall, I could have badly misconstrued what had occurred. My friends at the White House repeatedly assured me that I had seen LBJ in a singular mood. He had been provoked to querulousness at writers that night by something he had just read and associated me with the writing clan (although he was, for the most part, courteous enough), but I was not to interpret what I had witnessed as in any way representative of Johnson’s behavior. That construction of my visit gained credence when, not long after I saw him, the President announced that on October 8 he was to undergo surgery to have his gallbladder removed. He had first felt pain on September 7, two weeks before our interview, and the operation, which also resulted in the surgeon’s taking out a kidney stone, was so serious that he was compelled to spend most of the rest of the year at the ranch. (It would be there that he would shock sensibilities by pulling open his clothes to bare his abdominal scar.) So, then, Johnson’s cantankerousness that evening could be explained away as the result of intolerable pain. In late October The Economist wrote: “With the benefit of hindsight . . . it is tempting to speculate whether the bilious humor . . . should have been laid to incipient gall bladder trouble rather than to egocentricity.”

I now know better. There is today a mountain of evidence that Johnson’s comportment was not idiosyncratic: that he characteristically resorted to barnyard idiom, was fixated on television news, levied war against the media, was abusive to those around him and contemptuous toward those who might be regarded as his equals, vilified John Kennedy, and sought to leave FDR in his shadow—in sum, that he held a conviction of his own centrality in the universe bordering on egomania. That evening I had, unintentionally, been given an early, and extraordinarily extended, opportunity to see the President expose himself at a critical moment in his career when, having been lauded for his skillful assumption of the office after Kennedy’s death, having been returned to the White House in a landslide in 1964, and having carried the Great Society program through Congress, he was plunging the nation ever deeper into the quagmire in Southeast Asia.

Every so often, historians are polled about how Presidents should be ranked, and Lyndon Johnson has always been problematic. The ready explanation for the difficulty of rating him is that the same historians who acclaim his domestic programs are sickened by

This worrisome feature of Johnson’s delusions of grandeur had largely been covered up by the White House staff during his period of uninterrupted success, but in the very week saw him, Time published an apocryphal tale of the visit of West Germany’s Ludwig Erhard to the LBJ Ranch. “I understand you were born in a log cabin,” Erhard says appeasingly. “No, Mr. Chancellor,” Johnson barks back. “You have me confused with Abe Lincoln. I was born in a manger.”

There is one final aspect to Johnson’s conduct that evening that also figures in any assessment of his place in history: his loutish manner. Compared with the large issues of policy with which he dealt, that concern may seem trivial. Nothing I witnessed made me admire any less the President’s many achievements, especially in civil rights and the war on poverty. As George Reedy has said, “There is no doubt about his nastiness in dealing with individual human beings. But neither can there be any real doubt about his sincerity in trying to do something for the masses.”

Yet the boorishness he revealed in the interview is no small matter, for we are right to expect that our President, whatever his talents as policy maker and executive, will also be sensitive to his role as the most conspicuous exemplar of republican values. One administrator later said: “When I read some of the things the college kids write about Johnson, they make it very clear why they hate him. Johnson took something that was great and important in their eyes, and he made it small. It’s as though he defecated in the Oval Office. What they’re angry about, and not only the young, is the vulgarization of the presidency.” Any final reckoning on Lyndon B. Johnson is likely to say that however grievous were his failures abroad, he deserves a great deal of credit for advancing equality and justice at home, but it will also add that this immensely powerful man, who wanted to be thought of as the greatest President ever, all too readily debased the office he had sworn to uphold.