Authors:

Historic Era: Era 9: Postwar United States (1945 to early 1970s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Spring 2019 | Volume 64, Issue 2

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 9: Postwar United States (1945 to early 1970s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Spring 2019 | Volume 64, Issue 2

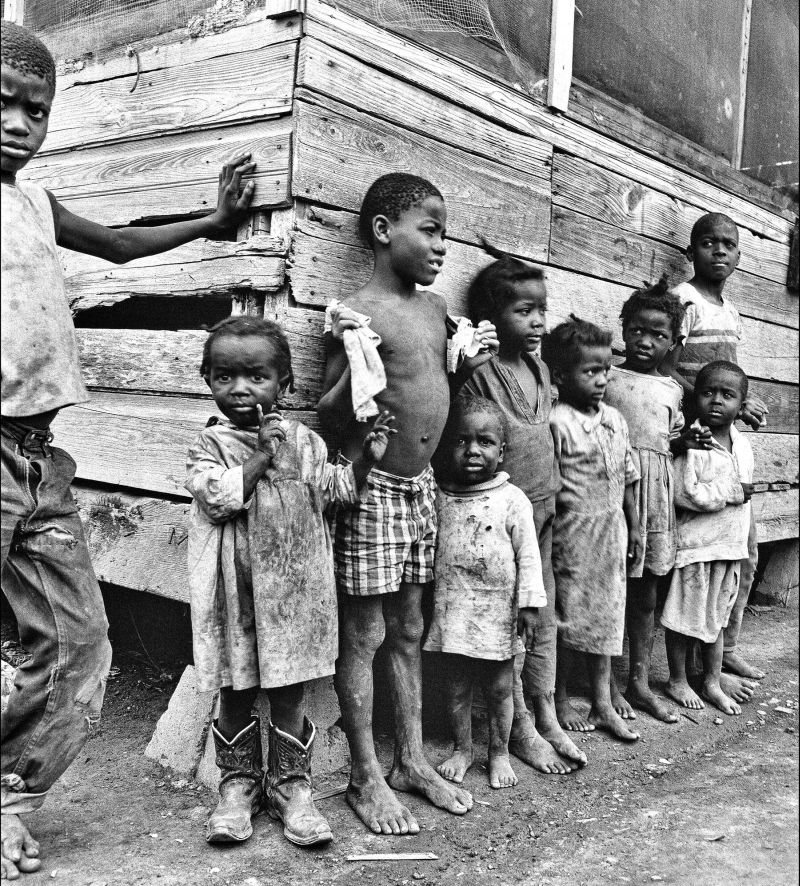

Senator Robert F. Kennedy, a son of America’s promise, power, and privilege, knelt in a crumbling shack in 1967 Mississippi, trying to coax a response from a child listless from hunger. After several minutes with little response, the senator, profoundly moved, walked out the back door to speak with reporters. He told them that America had to do better. What he was seeing, as he privately told an aide and a reporter, was worse than anything he had seen before in this country.

As he toured the Mississippi Delta, an impoverished cotton-producing region in the northwest corner of the state, that warm April day in 1967, Kennedy talked with mothers about how they fed their children. He looked in empty refrigerators and asked school children about their breakfast. The depths of deprivation he found in Mississippi stunned both Kennedy and, because of the press coverage that inevitably followed him, the nation.

Kennedy visited Mississippi in 1967, along with Senator Joseph Clark of Pennsylvania, as part of a Senate subcommittee’s examination of War on Poverty programs. His journey provides a useful lens to examine the impact of waves of change roiling the state and the nation at the time, as well as offers a deeper understanding of Kennedy’s growth as a leader.

His visit was a catalyst that drew out the extremes of Mississippi’s culture at the time. In Jackson, members of the Ku Klux Klan met him at the airport, carrying signs castigating him for his position on Vietnam and distributing flyers predicting his death. They were only echoing the hatred of Kennedy that many white Mississippians harbored because of his role as attorney general in the integration of the University of Mississippi, and other conflicts over civil rights in the state.

However, both black and white civil rights advocates on the frontline in Mississippi were unimpressed with his record. Many of them had struggled through life-threatening violence with little or no help from the Kennedy administration’s Department of Justice. They viewed Kennedy as a ruthless political dealmaker who put too much priority on placating powerful southern politicians in Congress. To advocates like Marian Wright, a 27-year-old NAACP attorney who was one of only five black lawyers in the state, his visit had the potential to be just another chance to be disappointed.

In contrast, Kennedy and his brother were heroes to many of the ordinary African American residents of the state. In fact, just about forty-eight hours after Kennedy landed in the state to the belligerent shouts of the Ku Klux Klan, hundreds of African Americans in Clarksdale cheered him and, as one journalist who was traveling with him recalled, “reached up to him like they were trying to touch the robes of Jesus Christ” at his last stop in Mississippi.

Jim Lucas." data-entity-type="file" data-entity-uuid="a43d16e5-62a3-4700-8f56-587e96aa6a85" src="https://www.americanheritage.com/sites/default/files/inline-images/Kennedy%20visiting%20Mississippi%2C%20photo%20by%20Jim%20Lucas.JPG" width="1249" height="680" loading="lazy">

On April 11, 1967, Kennedy, his aides, journalists, and civil rights advocates flew from Jackson, Mississippi to Greenville, where they toured job training classrooms and a cooperative farm for displaced farmworkers. After lunch, the group drove north through the Mississippi Delta.

With a federal marshal at the wheel, Kennedy, Wright, and his aide, Peter Edelman settled in for a thirty-eight-mile drive to Cleveland. They had been riding together since the airport in Greenville, and Wright found Kennedy, who rode in the front, to be a surprisingly pleasant companion.

“He was sort of relaxed; he was funny; he was honest,” she would later recall.

Always curious, Kennedy quizzed Wright about her life in Mississippi and what motivated her to work in such a troubled place. He asked what she was reading, and they discussed her selection, The Confessions of Nat Turner, and moved on to how to encourage children to read. She was firm with her boundaries, though. When he turned his questions to her personal life (When was the last time she went to the movies? When had she last gone on a date?) She quickly told him that it was none of his business.

Kennedy then shifted his attention to the attitudes of Mississippi people, black and white, toward the federal government. He quizzed Wright about the shift in rhetoric toward black power, which activists such as Stokely Carmichael of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) had first embraced publicly just a year earlier not too many miles from where she and Kennedy were traveling in Mississippi.

Though reasonable enough, these questions touched a nerve in the young NAACP lawyer. Wright was not naïve. She knew full well the political considerations Kennedy had wrestled with as attorney general: the need to placate powerful southerners in Congress; Cold War intrigue; the concerns about public opinion after a razor-thin victory in the 1960 election; and his role as his brother’s protector, just to name a few. But Wright knew something else, something that was more powerful, more visceral, more painful, than her intellectual understanding of a complex political situation.

Marian Wright knew the reality of Mississippi jails. Secret trials. Beatings. Lynchings. Snarling dogs loosed on children and old people. Medgar Evers, dying in front of his children from a sniper’s shot. James Meredith writhing on the highway. Vernon Dahmer, the flames and smoke from a firebomb searing his final gasps for breath. James Chaney, Mickey Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman, holes in their heads, buried under tons of Mississippi mud. To many of the people helping African Americans in Mississippi struggle to exercise their rights as ordinary citizens, the Kennedy Department of Justice had been, in fact, no such thing.

The failures of the Kennedy administration’s approach were clear to her from her first visit to the state over spring break as a young law student from Yale in 1961. The