Authors:

Historic Era: Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

September 2020 | Volume 65, Issue 5

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

September 2020 | Volume 65, Issue 5

Editor's Note: Nina Burleigh was National Political Correspondent for Newsweek and has written for numerous publications including Time, The New York Times, New Yorker, The Washington Post, and The Guardian. She is the author of seven books including a biography of James Smithson, The Stranger and the Statesman. Portions of this essay appeared in her most recent book, The Trump Women: Part of the Deal, about the women who have had the most profound influence on President Trump's life (formerly published as Golden Handcuffs: The Secret History of Trump's Women by Gallery Books, an imprint of Simon & Schuster).

Mary Anne MacLeod was the tenth and last child born to a fisherman and his wife, on May 10, 1912, in the tiny town of Tong on the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides. She was just a wee thing, as the islanders would say, only seven years old, when a catastrophe struck that would mark her people and her generation. Two hundred of the island’s finest young men drowned in the wreck of HMY Iolaire within sight of the village. The ship was bringing veterans home from World War I when it struck rocks in a storm early in the morning on New Year's Day and sank. The poor men who had survived years of combat died within sight of the harbor lights.

The tragedy was probably one of Mary's earliest memories. In the way that history shapes individuals, who then unwittingly shape history themselves, the disaster was a catalyst that ultimately sent the girl who would give birth to a president far away from her home.

The Isle of Lewis, a windblown speck of rock and peat at the northerly edge of the Hebrides, had been controlled by local clan chiefs, the MacLeods, MacDonalds, Mackenzies, and MacNeils. In the nineteenth century, the English and their allies the landed Scottish lords instituted a brutal policy called the Highland Clearances, expelling peasants from farms and communities all over northern Scotland in order to empty the land for sport hunting and sheep grazing. Crofters, who had lived for centuries on the land, eking out a bare subsistence from the rocky soil by constructing “lazy beds” on which to grow potatoes and other crops that could withstand the fierce and ever-changing weather, lost everything.

Genealogists believe that Mary Anne MacLeod’s ancestors were among the poor farmers kicked off their plots by the landowners, and forced to live for generations in destitution in the small towns to which they had migrated seeking food, shelter, and work. Her branch of the MacLeod family had remained on Lewis through the hard years of the 1800s, while tens of thousands of mainland Scots and Hebrideans, facing starvation, emigrated to Canada — some under threat of force.

When Mary Anne was born, the remaining islanders maintained ancient traditions, crofting as tenants, fishing on all but the stormiest of days, and speaking Gaelic at church and school even as the English overlords discouraged it.

Mary Anne was born in a croft house, which her father had owned since 1895. The two-bedroom house had been converted from an ancient and indigenous island “blackhouse” — constructed of stone and with a thatched roof, which let smoke from the open peat fire seep out without need of a chimney. Ten siblings, the two MacLeod parents, and probably some grandparents, all shared the cottage.

Mary Anne learned speech, songs, and psalms in a Gaelic-speaking household. When she was old enough, she studied English, her second language, along with other fishing and crofting children at the little Tong school. On an American immigration form, Mary Anne reported that she was educated to the equivalent of America’s eighth grade, meaning she left school at around age thirteen or fourteen, presumably to work on the croft or in some other job to help boost the family income.

The Isle of Lewis was and still is deeply religious, and at the time it was experiencing a series of hard-core revivals with a tinge of popular rebellion against the establishment. Church was serious business. Women and men both wore black to services, and four Sunday services made the Sabbath a daylong affair.

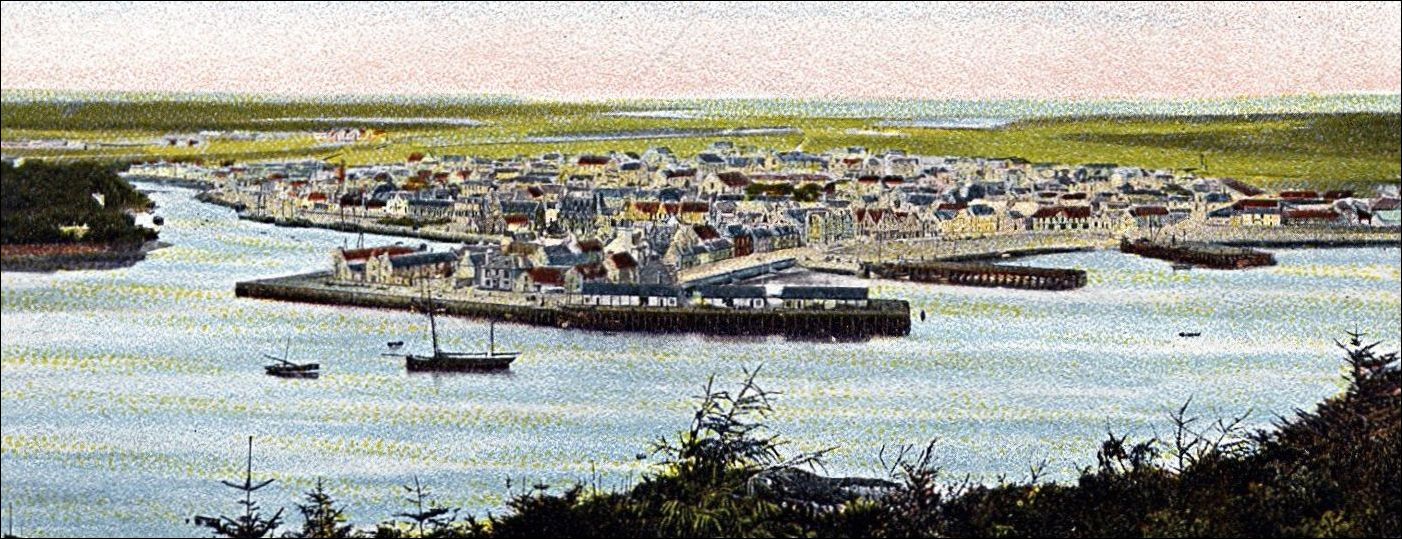

The MacLeod family belonged to the Scottish Free Church, a relatively more conservative congregation, in the nearby town of Stornoway. The dignified gray stone structure was planted on the gentry’s street, Matheson Road, lined with handsome brick mansions built by and for the families of the local merchants and wealthier landowners. To distinguish the residents of Matheson Road from the rest of sheep-and fish-smelling islanders, in their muck boots and oilers,