Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

February 1969 | Volume 20, Issue 2

Authors: James Thomas Flexner

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

February 1969 | Volume 20, Issue 2

After the fighting—after Trenton, Valley Forge, Monmouth, and Yorktown—after all the sleeplessness and the care, George Washington longed to return to the reassuring routine of his beloved Mount Vernon. This dream of return came true just before Christmas of 1783; already past fifty, the General looked forward to spending his remaining years at his favorite occupation, that of a Virginia country gentleman. He had plans to expand and embellish his ancestral home, to improve his land, and to put in order his neglected financial affairs. He also relished the thought of again riding for pleasure, of limiting with his dogs, of merely silting on his veranda and watching the familiar Potomac flow placidly to the sea. The General was, in fact, full of those hopes and those longings which have occupied the thoughts of all returning soldiers. It is this period of Washington’s life that the noted biographer and historian James Thomas Flexner treats of in the narrative that follows. This is the first of six articles which will appear in AMERICAN HERITAGE; subsequent installments will cover Washington’s return to national life, his inauguration, the political and social aspects of his Presidency, and his retirement and death. The series is taken from the final volume of Mr. Flexner’s three-volume study of Washington, now in work. Like the first two volumes, George Washington: The Forge of Experience and George Washington in the American Revolution, it will be published by Little, Brown.

—The Editors

George Washington remembered that when he woke up in the silent mornings his mind would instantly become a whirlpool of grievous things. Urgency was upon him as it had been daily for his eight years as Commander in Chief: the need to clothe thousands of naked men, fill empty bellies, procure gunpowder, write and persuade Congress; the need to build defenses, place cannon, withstand attack with inadequate forces. He had to march, explore strange countrysides, interrogate spies and prisoners. How could he find some way to defeat a stronger enemy, some miraculous way to achieve what seemed past the power and will of an emerging nation: victory that would end this interminable war and establish the independence of the United States?

Then, as his long body thrashed around in an oddly comfortable bed, a strange realization Hooded over him. Although engulfed in darkness, for this was winter and he always woke early, Washington became aware that outside the windowpanes there stretched not a military camp but the peaceful countryside of his childhood memories. The sighing ho heard was the wind in his own trees, and out there the Potomac, his ancestral river, pulsed gently under the bluff

The General had brought home with him to Mount Vernon a priceless acquisition, the very jewel he had longed for in his most ambitious dreams. Ever since he had become familiar as a youth with the Stoic philosophy, he had considered that the greatest reward any man could earn was the confidence, affection, and gratitude of his countrymen. It had been to win tins boon that, refusing pay and spurning opportunities to grasp further power, he had faithfully served his fellow citizens as military commander year after unbroken year. Now the labor was over; this admiration, this love, this gratitude were his to enjoy, as a man would turn a many-faceted crystal quietly in his hands.

Washington’s brightest personal hope had been, as he dreamed by the campfires, to merge this achievement, in memory and in reality, with the delights of the peaceful walks he had inherited from his ancestors and had himself happily pursued. All was to be contained within those magic acres which his dear dead half-brother Lawrence, who had willed them to him, had named Mount Vernon.

HERE, fashioned from wood on land which his grandfather had purchased in 1674, was tangible continuity, the past moving with beauty into the present. When his own prosperity had increased, Washington had not, as his neighbor George Mason had, torn down his ancestral house and erected a new elegant structure according to a plan bought from a professional architect. The center of Mount Vernon rested on seventeenth-century foundations. The room where on domestic evenings George sat with Martha while her grandchildren prattled was the same cramped space he had himself prattled in as a child. Placing furniture was difficult because the first builder had parsimoniously erected the fireplaces in the corners of the rooms so that one outside chimney could serve a pair. Washington had not altered this clumsiness, although

Above and on both sides of the tiny old rooms stretched an extensive house which Washington, his own architect, had improvised in stages as his needs had grown. There were clumsy solutions: unsupported beam-ends, false windows where the façade argued with the interior, an extensive waste area between the floor of one room and the ceiling of another. But there was also harmony, dignity, and a lyrical sobriety that testified to the temperament of the creator.

“The mansion house itself, though much embellished but yet not perfectly satisfactory to the chaste taste of the present possessor, appears venerable and convenient.” So wrote David Humphreys, an old friend with literary pretensions, in 1786. “The superb banqueting room has been finished since he returned from the army. A lofty portico, ninety-six feet in length … has a pleasing effect when viewed from the water.”

The whole area was so flat that the “mount” on which the house stood, although it rose only two hundred feet above the Potomac River, seemed an imposing height. From the two-story colonnaded porch (which was Washington’s invention and was to have many descendants in the South), one could walk a hundred paces on a flat lawn. Then the land dropped to the river “about 400 paces, adorned with a hanging wood and shady walks,” according to one visitor. From the mount, “the perspective view” was magnificent, the river being sonic two miles wide and taking a wide curve so that it seemed to embrace Washington’s extensive acres. Some foreigners, it is true, found the broad panorama of the Maryland shore deficient in “houses and villages,” but the mostly unbroken vegetation pleased the eye of a man who had spent so many still hours in the wilderness. Near both flanks of the house he had, indeed, created artificial wildernesses that mediated between the wild and the planned: woods full of botanical specimens and flowering trees.

On the land side of the mansion, a lawn of about five acres was shaped, by the twin driveways that defined its outer limits, to resemble a copiously rounded bell. From each periphery, “gravel walks planted with weeping willows and umbrageous shrubs” led to large, shield-shaped gardens contained within decorative brick walls. One garden was devoted to flowers. Although the other grew kitchen vegetables, it too was planned for promenading, being laid out in squares by walks lined with fruit trees and low box hedges.

An English visitor commented on the “astonishing … number of small houses the General has upon his estate.” These included a greenhouse, a schoolhouse, extensive stables, quarters for white servants and slaves, shops for brewers, carpenters, blacksmiths, and even “a well appointed store” that served the neighbors, family, and servants. According to Humphreys:

Washington had comforted himself in the military camps with the thought that, after victory had somehow been achieved, lie would return to Mount Vernon and “contemplate” in “philosophic retirement” the excitements and anguishes he had experienced, the rigors lie had overcome. It was not only his own restlessness that undermined this vision: his retirement could not conceivably be like that of an ordinary man. The triumphant hero, who like the legendary Cincinnatus had returned to the plow, was the most conspicuous symbol of the most portentous political event of the eighteenth century. His character and appearance and way of life fascinated not only his fellow Americans but the philosophers, soldiers, and curiosity-seekers of the entire Western world.

Many visitors came by invitation, for Washington rarely wrote to a companion of the old, hectic days without asking him to Mount Vernon. Others brought letters of introduction, or were men of moment who by definition felt entitled to call on “his Excellency.” Some were supplicants for this or that. Some appeared utterly without auspices. Thus Washington noted, “A Gentleman calling himself the Count de Cheiza D’Arteignan, Officer of the French Guards, came here to dinner, hut bringing no letters of introduction, nor any authentic testimonials … I was at a loss how to receive or treat him.” Washington invited him to stay for dinner and the evening, and extended the invitation until the bogus officer (there is no record of him in the French army lists) had spent two nights at Mount Vernon. Then Washington sent him “with my horses today, at his own request, to Alexandria.”

Washington was under pressure to put up all callers—with their servants and horses—who arrived toward evening, since the nearest inn was in Alexandria nine miles away, a journey of several hours. The road was rough and travelers had to stop every few minutes to open and then close gates built across the road to control the local cows and pigs. Mount Vernon, so Washington wrote, could be “compared to a well-resorted tavern, as scarcely any strangers who are going from North to South, or from South to North, do not spend a day or two at it.” But, of course, a Virginia gentleman could charge nothing for room and board.

To intimates like Humphreys, whom he invited for long visits, Washington would write, “The only stipulations I shall contend for are, that in all things you shall do

However, Washington’s guests never had cause to complain of being treated slackly, of any lack of opulence or elegance. Their host liked to talk of republican simplicity, and he did achieve it in the sense that Mount Vernon was very much less grand than the mansions of Europe: it could have been absorbed twenty times over in a great English country house. But for America it was sumptuous, and Washington did his best to improve it in the latest taste.

Having written a merchant for seventy yards of red and white livery lace, he added,

Off to an English gentleman went a request for information about stucco, which he understood was the present taste in England for finishing interiors. He wanted to know

Washington had so designed Mount Vernon that he and his family had a wing of their own, which opened into the rest of the house only on the ground floor: here was his study, the bedroom he shared with Martha, dressing rooms, and rooms for the grandchildren. This arrangement provided as much privacy as he could hope to achieve, but it was no protection against unexpected interruption. More often than not, when he returned from his usual morning tour of his farms he would find that departures and arrivals had altered the crowd of guests he had said good night to on the previous evening. Often completely strange faces stared at him with a curiosity embarrassingly undisguised.

The man the newcomers studied, although he moved with a springy lightness, was for those days a very big man, between six feet and six feet three inches in height. His shoulders were narrow and sloping but his limbs—forearms and thighs, hands and feet—startlingly large. His head was massive. The forehead, under a plentiful thatch of graying hair, was broad and high, yet it seemed small when compared to the rest of his face. Set wide apart, his gray-blue eyes were deep

Such a head could inspire fear, but every strength in Washington’s appearance, as in his character, incorporated within it its own restraint. He gave an impression of reserve tempered with affability. His eyes, unless quickened by recognition of an old friend, lurked in their deep sockets without animation. Some visitors considered him austere; others were amazed to conclude that the great man was shy. An Englishman noted, “He speaks with great diffidence, and sometimes hesitates for a word, but it is always to find one particularly well adapted to his meaning. His language is manly and expressive.”

Having ceremoniously greeted each visitor, Washington would sit with them for a few minutes and then go upstairs to change out of his farming costume. In half an hour or so he would reappear, wearing on one occasion, as a guest noted, his hair neatly powdered, a clean shirt, a new plain drab coat, and white stockings.

Dinner was served at two. It was always ample and often luxurious, but Washington did not stuff himself. He commonly ate a single dish and drank from half a pint to a pint of Madeira. If the company permitted of relaxation, he remained “an hour after dinner in familiar conversation and convivial hilarity,” wrote Humphreys.

When he finally rose from the dinner table, Washington disappeared into his library or outdoors into his gardens. Toward evening, he drank “one small glass of punch, a draught of beer, and two dishes of tea.” Although “a very elegant” supper was served to his guests, he did not appear but went to bed at nine. If, however, intimate friends or individuals who brought interesting news arrived toward evening, Washington would come to the supper table. Then he would drink several glasses of champagne, get “quite merry,” and laugh and talk “a great deal.”

A fairly typical visitor was a young merchant, Elkanah Watson, who shared with Washington a passion for canal building. The General, Watson wrote,

Watson had a bad cough. Washington (who himself avoided taking medicines) tried vainly to press some nostrum on his visitor. During the night, Watson’s cough increased, and then he heard a noise. “On drawing my bed-curtains, to my utter astonishment, I beheld Washington himself, standing at my bedside, with a bowl of hot tea in his hand. I was mortified and distressed beyond expression.”

Among the more complimentary—and plaguing—of Washington’s visitors were artists who wished to spread his likeness through an eager world. From the time he was first painted as an uncelebrated Virginia planter, Washington had found it embarrassing to sit still and be studied. During 1785, he responded to a letter introducing the English artist Robert Edge Pine:

It is a proof among many others of what habit and custom can effect. At first I was as impatient at the request, and as restive under the operation, as a Colt is of the Saddle. The next time, I submitted very reluctantly, but with less flouncing. Now no dray moves more readily to the Thill, than I do to the Painters Chair.

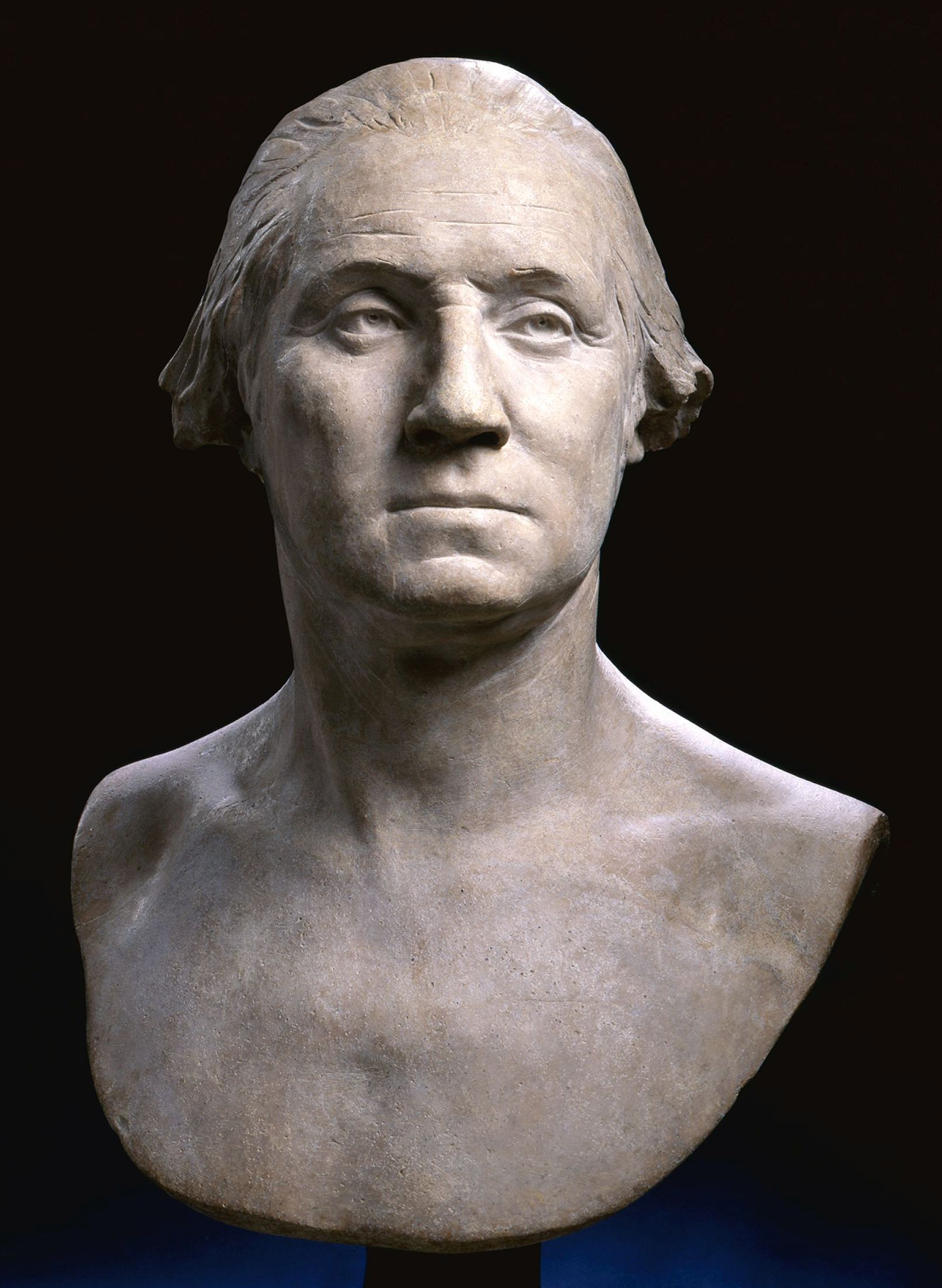

Sculptors came, first the obscure Joseph Wright, operating on a private speculation, and then the celebrated French artist Jean Antoine Houdon, who had been employed in Paris by Jefferson and Franklin to create a heroic statue which had been commissioned by the Commonwealth of Virginia. Both sculptors started out by making a life mask. Concerning Wright’s effort, Washington stated:

Houdon appeared with three assistants. Jefferson, who seems to have feared that Washington would hesitate to receive an artist, had written that the sculptor moved in the best circles. Jefferson need not have worried: Washington was used to entertaining men of all ranks. He lodged the sculptor and his assistants for more than two weeks and then sent them up the Potomac in his “barge.” They carried with them not only the life mask but casts and measurements of his body, all to be combined into the statue in Paris.

Eventually Washington wrote

In May, 1785, there rolled up the driveway one of England’s most notorious women, Catharine Sawbridge Macaulay Graham, who had struck out for liberty and excoriated the Tories in her eight-volume History of England from the Accession of James I to that of the Brunswick Line. She surely wore more rouge than any other lady ever entertained at Mount Vernon—John Wilkes described her as “painted up to the eyes” and looking “as rotten as an old Catherine pear”—and she had in tow a lower-class youth of about twenty whom, at the age of almost fifty, she had married, to the publicly expressed despair of her elderly lover and the titters of British society. The bridegroom’s elder brother was a notorious quack who operated at fashionable Bath a Temple of Health which featured the electrified royal Patagonian bed that was supposed to enhance sexual pleasures and was reputed to be the inspiration of the marriage of the elderly “historian in petticoats” to her juvenile surgeon’s mate.

While making expansive gestures, Mrs. Graham talked at the top of her lungs almost without stop, laying down the law on political matters. Washington was deeply impressed with this friend “of liberty and of mankind” who was clearly as brilliant as she was eccentric. He wrote General Henry Knox, “A visit from a Lady so celebrated in the Literary world could not but be very flattering to me.” In sending out invitations to dine with her and her boyish husband, he explained to the neighbors that “I wish to shew them all the respect I can.” He placed his military records in her hands “for her perusal and amusement.” When the Grahams departed after a stay of ten days, Washington accompanied them some distance on the road. The General and the lady continued to correspond during the many years until she died, her letters crammed with political advice, his written with that special care he employed in addressing those whom he considered more educated than he.

The man who had ridden away from Mount Vernon to lead a revolution that pointed to the future of the Western world had come back eager to gather soothingly around him his personal past.

Less than a month after he had returned his commission as Commander in Chief to the Continental Congress, Washington wrote to ask if he could not have the document back. The paper, he explained, “may serve my Grand Children some fifty or a hundred years hence for a theme to ruminate upon, if they should be contemplatively disposed.”

Washington had no grandchildren and no children to create them. He could not have been referring to his wife’s grandchildren, descended from her first husband, since he did not consider them his own. He had, he wrote on another occasion, “no family … nobody to provide for.…”

Yet the man who had achieved so much could not give up the hope that the children who were so freely accorded to others would in the end be vouchsafed to him. True, he had been married to Martha for twenty-five years, and always without issue. The implications raised by his wife’s fecundity during her brief first marriage—her womb quickened in rapid succession four times—could not have been excluded from the ruminations of a man who so steeled himself to look at facts. Yet the magnificent athlete could not accept the conclusion that he was sterile. Surely, his childless state was linked to his marriage with Martha!

“If Mrs. Washington should survive me,” he decided, “there is a moral certainty of my dying without issue.” However, even a man who loved his wife as George Washington did could not exclude from his meditations an alternative. Its possibility was, indeed, strengthened because Martha was now “scarce ever well.… Billious Fevers and Cholics attack her very often, and reduce her low.” He tried to comfort her by ordering from England “a handsome and fashionable gold watch,” the hands to be “set with Diamonds,” but he could not help speculating what would happen if she did not survive him and he survived her.

Would he marry again? Would his new wife give him a child? He feared that she would not if he selected “a woman of an age suitable to my own.” But supposing he married “a girl?” He hoped that, “whilst I retain the reasoning faculties, I shall never marry a girl,” yet he remained haunted by the vision of a child of his own. Not only did he write Congress that his commission be returned as a souvenir for his grandchildren, but he was careful not to exclude from his promises to his collateral heirs the possibility that a babe might suddenly appear and from the cradle preempt all.

The most serious problem in Washington’s personal relations concerned the oldest connection of all and the psychologically most intimate. His mother was in her late seventies but, as he wrote, in “good health” and “in the full enjoyment of her mental faculties.” As soon as the weather had abated after his first return to Mount Vernon, Washington had journeyed to Fredericksburg to pay her

It was, however, normal for him to avoid, as far as possible, lengthy sessions in the presence of that maternal force. If, now that her son stood before her as one of the world’s acclaimed heroes, she added a word to the general praise or did not try to make him feel inadequate, it would have been a prodigy. She had been, during the Revolution, so uncomplimentary about Washington’s activities that she had generally been considered a Tory. To those who had lauded her son in her presence she had replied that he was off doing things that were none of his business and was allowing her to starve. Washington had heard “on very good authority that she is upon all occasions and in all companies complaining of the hardness of the times, of her wants and distress; and, if not in direct terms at least by innuendoes, asking favors.” This, Washington wrote from one of his military camps, was “too much,” when in fact she was provided with everything she needed or asked for. However, Washington quickly added that he would prefer not to remonstrate with his mother himself. He urged his favorite brother, John Augustine Washington, to do so.

Down the years, mediation by John had kept the relations between George and his mother from open explosion, but in January, 1787, the mediator died. A month later, Washington’s control broke.

His mother had again asked for money. He sent her fifteen guineas, which he stated was all the cash he had, and then pointed out angrily what a drain on his estate her activities had been. She had requisitioned all the supplies from a plantation he conducted near Fredericksburg, and during the war he had advanced her between three and four hundred pounds from his own pocket. Despite this, she had talked in such a way that he was “viewed as a delinquent and considered, perhaps by the world, an unjust and undutiful son.”

She should rent her farms, which would supply her with “ample support”; break up housekeeping; hire out all her servants except a man and a maid; keep only a phaeton and two horses; and live with one of her children. “This would relieve you entirely of the cares of this world and leave your mind at ease to reflect undisturbedly on that which ought to come.” Since her expenses would use up only a quarter of her income, she could “make ample amends to the child you live with.” She might then be “perfectly happy,” that is, “if you are so disposed, … for happiness depends more upon the internal frame of a person’s mind than on the externals

Washington hastened to add that he was not suggesting that she come to Mount Vernon: “Candor requires me to say that it will never answer your purposes in any way whatsoever.” Since the house was always crowded with strangers she would be forced to do one of three things: be always dressed for company, appear in dishabille, or be a prisoner in her own chamber. The first, she would not like as being too fatiguing for one in her time of life. The second, he would not like, as his guests were often “people of the first distinction.” Nor would it do for her to stay in her own room, “for what with the sitting up of company, the noise and bustle of servants, and many other things, you would not be able to enjoy that calmness and serenity of mind which, in my opinion you ought now to prefer to every other consideration of life.”

Mary Washington did not relish her son’s desire to make her into a conventional fireside figure of tranquil old age. She did not rent out her land or break up her personal housekeeping. But, on the other hand, she did not permit George’s interference and scolding to displace him as the favorite of her children. When she died in 1789 she left the lion’s share of her estate, including her best bed and best dressing glass, to the descendant who, from all appearances, least needed the bequest; to George Washington.