Authors:

Historic Era: Era 10: Contemporary United States (1968 to the present)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Fall 2017 | Volume 62, Issue 5

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 10: Contemporary United States (1968 to the present)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Fall 2017 | Volume 62, Issue 5

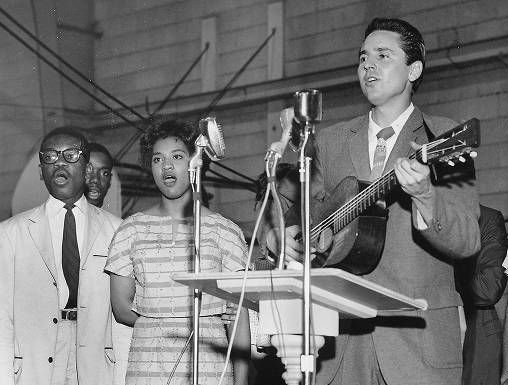

In April 1960, 126 young civil rights activists joined together in song in Raleigh, N.C., as they gathered for the founding of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, better known as SNCC. “Guy,” someone shouted, “Teach us all ‘We Shall Overcome.’”

Many of the volunteers had met the folksinger Guy Carawan five weeks earlier at a workshop on “Singing in the Movement” at the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee. Joined there by banjo-player Pete Seeger, Carawan and the group had sung numerous fast and slow protest songs that would come to be repeated over and over as the civil-rights struggle gained momentum. But it had been a new version of an old African-American spiritual that Seeger crafted that had been the highlight of the weekend.

Carawan had learned “We Shall Overcome” earlier, but most of the 70 participants at the Highlander school were hearing it for the first time. Now, at the SNCC founding convention, they wanted to sing it again. Its simple words and music would go on to become the anthem of the civil-rights movement, sung at rallies and marches, and even in jails. When the movement for racial equality lost steam in the next decade, it became the marching song in battles for freedom around the world.

How that happened reminds us that music has long been intertwined with protest. It has had an impact that has helped reform movements succeed. Growing out of slavery, adopted in black churches at the turn of the 20th century, picked up by laborers striking for better working conditions and then by civil-rights marchers, throughout its long history “We Shall Overcome” has helped draw together people fighting for a better life.

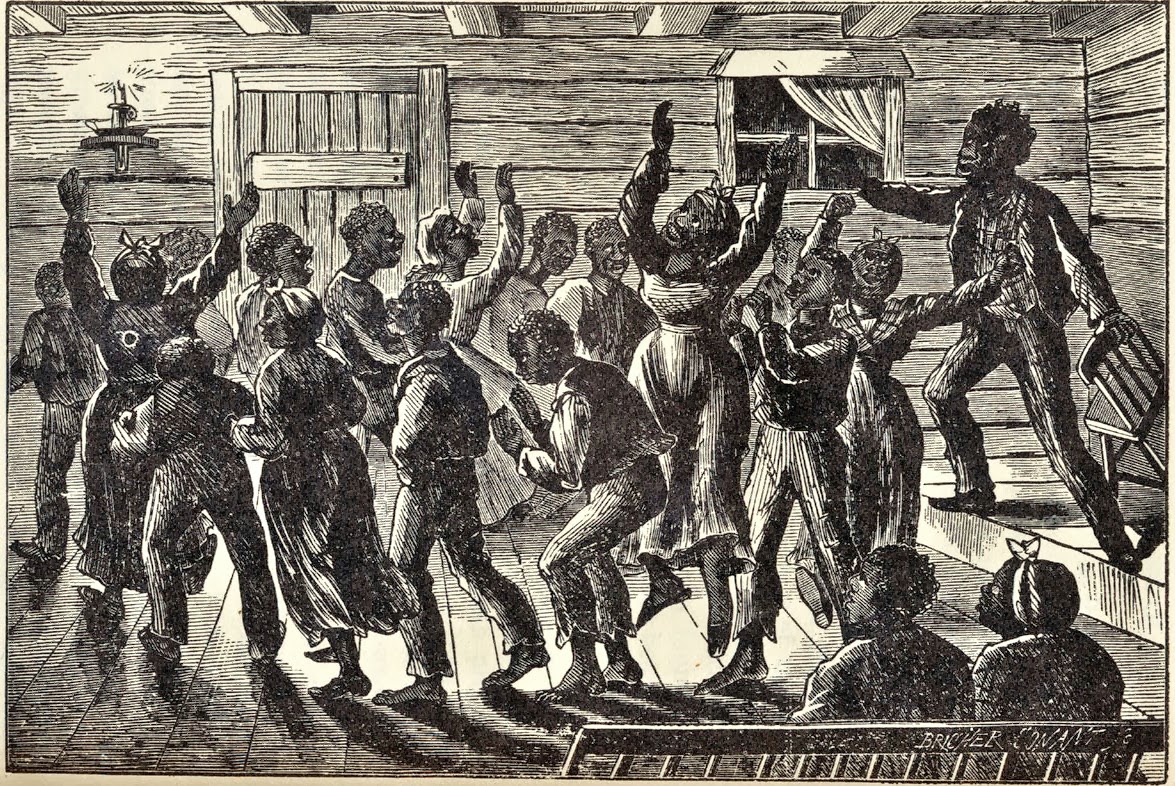

The song, with its promise “We shall overcome some day,” probably dates back to antebellum days, when slaves sang phrases such as “I’ll be all right someday” as they worked in the fields. Much of their music had roots in African songs brought over during the brutal Middle Passage to the New World. The patterns of call-and-response and repetition provided a sense of community and participation in a hostile and forbidding world, as well as an outlet for ideas about freedom that could not otherwise be voiced.