Authors:

Historic Era: Era 10: Contemporary United States (1968 to the present)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Fall 2017 | Volume 62, Issue 5

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 10: Contemporary United States (1968 to the present)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Fall 2017 | Volume 62, Issue 5

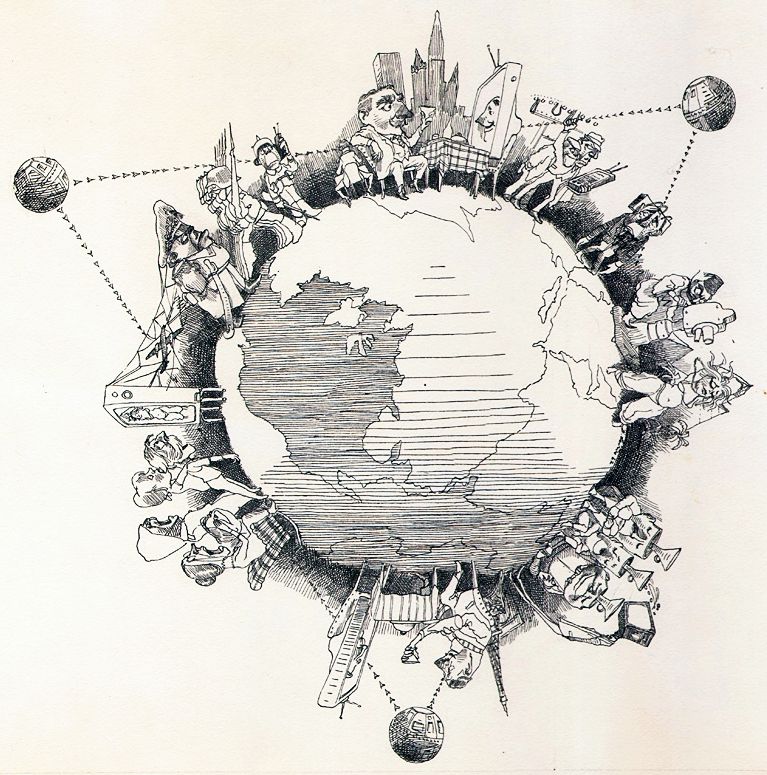

Today, Arthur Clarke is remembered as a writer of science fiction and the screenplay for the 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey. But Clarke was also a serious futurist and one of the first writers to suggest that rockets could be used for communication, not just military purposes.

During World War II, Clarke had served in the Royal Air Force as a physicist working on early-warning radar defense. In 1945 he wrote a seminal essay in Wireless World pointing out that a German rocket could get into orbit around the earth with a little more fuel (and no heavy bomb). "It will be possible in a few more years to build radio-controlled rockets which can be steered into orbits beyond the limits of the atmosphere and left to broadcast scientific information back to the earth." Subsequently, he wrote a number of books on the subject including Interplanetary Flight (1950) and The Exploration of Space (1951).

After Alan Shepard became the first American in space in 1961, American Heritage asked Clarke to write about how our efforts in space would affect daily life. The resulting essay was published in our sister magazine, HORIZON, in February, 1962.

Who would have then believed that the coming communications revolution would so completely change our lives? Clarke seemed farfetched when he predicted "instant mail without mailmen," telecommuting, cheap long-distance calls, and many other implausible advances.

Earlier, in 1958, American Heritage had published an essay by Clarke on the trans-Atlantic cable.

—The Editors

The writer who first proposed them foresees:

· The ten-cent phone call to anywhere

· The decline of travel

· The death of the printed newspaper

· Every library book on your home screen

· Instant mail without mailmen

· The end of censorship

· A universal language (but which one?)

In the ability to communicate an unlimited range of ideas lies the chief distinction between man and animal; almost everything that is specifically human arises from this power. Society was unthinkable before the invention of speech, civilization impossible before the invention of writing. Half a millennium ago the mechanization of writing by means of the printing press flooded the world with the ideas and knowledge that triggered the Renaissance; little more than a century ago electrical communication began that conquest of distance which has now brought the poles to within a fifteenth of a second of each other. Radio and television have given us a mastery over time and space so miraculous that it seems virtually complete.

Yet it is far from being so; another revolution, perhaps as far-reaching in its effects as printing and electronics, is now upon us. Its agent is the communications satellite.

The suggestion that satellites might