Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

July/August 1988 | Volume 39, Issue 5

Authors: Edward Hoagland

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

July/August 1988 | Volume 39, Issue 5

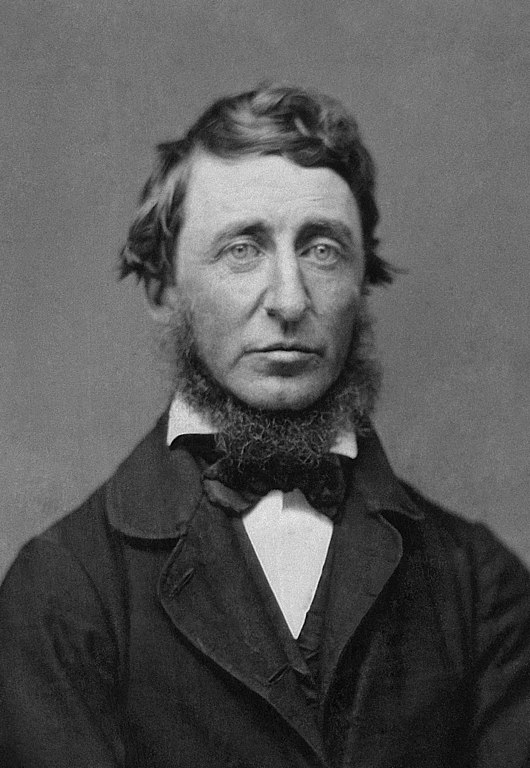

Henry David Thoreau, who never earned much of a living or sustained a relationship with any woman that wasn’t brotherly—who lived mostly under his parents’ roof (and is buried simply as “Henry” in his father’s graveyard plot), who advocated one day’s work and six days “off” as the weekly round and was considered a bit of a fool in his hometown, sometimes even having to endure the nickname “Dolittle”—is probably the American writer who tells us best how to live comfortably with our most constant companion, ourselves. We find ourselves brought to life in Thoreau’s books if we too want to simplify our roster of obligations and clutter of habits and possessions, to be independent of wage-slave constrictions and social obiter dicta, and if we know that common sense and honesty do not always coincide with prevailing tastes and majority opinion. His masterpiece, Walden, is controversial because it goes against the grain of go-getterism, conventional social arrangements, and established religion. But when he went traveling, he became a more convivial man of letters, and particularly in the Maine woods, “far from mankind and election day,” he discovered so little to displease him that there’s no hint of churlishness or reclusiveness in his buoyant account, even on the eve of the Civil War, whose roiling approach profoundly disturbed him.

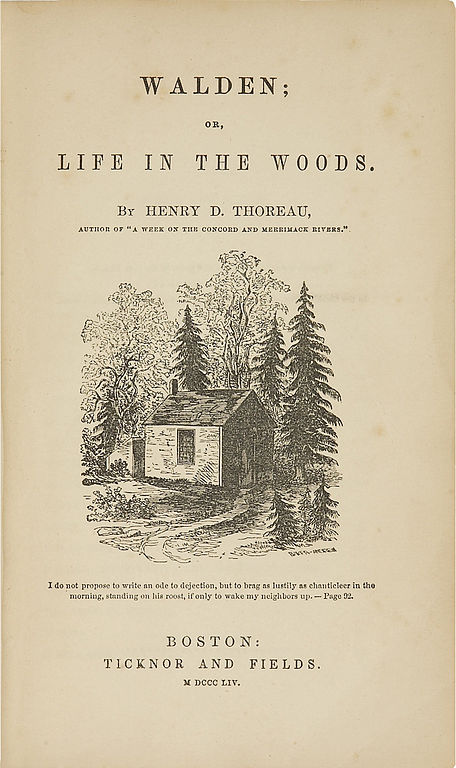

Born in 1817, Thoreau died of tuberculosis in 1862, in his mid-forties, having kept a voluminous journal from the age of twenty but having published only a smattering of magazine articles and poems and two books, the first of them at his own expense. A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers appeared in 1849 and sold only 219 copies in four years. Its failure commercially delayed for five years the scheduled appearance of Walden (1854), which then took five years to sell out a printing of 2,000 copies, priced at a dollar apiece. His fame—and two more marvelous books, The Maine Woods (1864) and Cape Cod (1865), edited by his sister Sophia and his friend Ellery Channing from manuscript versions and magazine pieces—was posthumous. Nevertheless, it’s easy to exaggerate Thoreau’s obscurity at the time of his death, which in no way equaled Herman Melville’s parched solitude, for instance, in the four decades after Moby Dick came out in 1851. These two great American Romantics were almost exact contemporaries, like their masterpieces, and neither’s achievement was recognized for the better part of a century. But Thoreau had had the good luck to be born in Concord, Massachusetts, where he was thrown into contact with many of the literary figures of the day, notably Ralph Waldo Emerson, who became his mentor and champion, Bronson Alcott, Margaret Fuller, Nathaniel Hawthorne, James Russell Lowell, and Orestes Brownson, and on a wider scene

As a young man at rather loose ends, Thoreau had lived for three years in Emerson’s house, and it was Emerson who bought and loaned him the land on the shore of WaIden Pond where he built a ten-by-fifteen-foot cabin and wrote the bulk of his first two books. During those busy twenty-six months (1845-47) he also made his first trip to the Maine woods, and spent a night in Concord’s jail, protesting paying taxes for the Mexican War, which was unpopular among educated New Englanders as being waged in the furtherance of slavery—an experience that produced his classic essay “Civil Disobedience.” Emerson’s kindnesses, patronage, and advocacy were of crucial importance to Thoreau’s career, and Thoreau made no substantial departure from Emerson’s Transcendental ideas as enunciated in the older’s man earlier, already famous essays like “Nature,” “Self-Reliance,” and “The Over-Soul.” It was not in the ideas but the expression of them that Thoreau surpassed his friend, with aphorisms such as “We are constantly invited to be what we are”; or “The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation”; or “I have traveled a good deal in Concord”; or “The sun is but a morning star.” One might argue with each of these statements, but each is so succinct as to sum up an ordinary essay, and the manner in which he lived was succinct enough to reinforce every epigram he wrote. Planting beans next to his pondside cabin (“seven miles” of bean rows: he meant to be self-sufficient in beans, to make “the earth say beans instead of grass”), he can be reduced to the ineradicable simplicity of Johnny Appleseed or Paul Bunyan, Daniel Boone or Nathan Hale, Babe Ruth or Paul Revere, as a national archetype.

Transcendentalism was the liveliest intellectual movement of nineteenth-century America. It presupposed the immanent presence of God within both man and nature, more recognizable by intuition than by

During this extraordinary half-decade — Whitman’s initial version of Leaves of Grass came out in 1855, a year after Walden , and Hawthorne’s Scarlet Letter in 1850, one year before Moby Dick —nature was much celebrated with a New World imprint, and Thoreau was the most exuberant participant. “The light which puts out our eyes is darkness to us. Only that day dawns to which we are awake. There is more day to dawn,” is his exhortation in closing Walden . That the ideas he was espousing had not started with him made his task easier, because in literature, unlike science, what matters is not who’s first but who has said it best, and he could tinker with, elucidate, illustrate, reformulate, and perfect them. Here, for example, is Emerson’s earlier statement of Thoreau’s pithy dictum, “I have traveled a good deal in Concord”: “I am not much an advocate for traveling,” said Emerson, “and I observe that men run away to other countries because they are not good in their own, and run back to their own because they pass for nothing in new places. For the most part, only the light characters travel. Who are you that have no task to keep you at home?”

Emerson did not lack boldness. On slavery, he was “an abolitionist of the most absolute abolition,” he said, and he also addressed the 1855 Women’s Rights Convention in Boston. For

Thoreau, though far from being the first “nature writer,” has come to stand for the whole genre. He does seem typical in that he was a social conservative but a political radical. Such authors don’t welcome industrial or technological change, which only serves to remove mankind still further from nature, and they are often furious at human-scale inequity and wars of imperial conquest, which tend to strike them as outgrowths of that change. Slavery and the Mexican War of the 184Os outraged Thoreau and Emerson much in the way that the civil rights struggles and the Vietnam War engaged the passions of nature lovers in the 1960s. It is no accident that Thoreau, and not some other classic writer, pioneered the notion of civil disobedience—affecting Tolstoy and inspiring Gandhi—and that he delivered orations on behalf of the fiery revolutionist John Brown. “The greater part of what my neighbors call good I believe in my soul to be bad, and if I repent of anything, it is very likely to be my good behavior. What demon possessed me that I behaved so well?” he wrote in Walden . To Emerson’s mild dismay, Thoreau was a revolutionary.

But what has made him more imperishable was a deeper radicalism, nearly as pervasive as his love of nature. He was writing Walden during the height of the California gold rush and of the larger westering fever of hope and excitement, when the existence of the Oregon Trail seemed to represent an elixir of wealth and youth. But he merely dismissed the premises of trying to pile up money or of changing the scene of one’s efforts. It was exploring oneself that mattered, and witnessing each day at home. (The continent might scarcely have been settled if Thoreau’s priorities had held sway.) As one of a line of writers going back to Rousseau, he said, “I should not talk so much about myself if there were anybody else whom I knew so well,” and like Walt Whitman, he devoted his life to presenting his enthusiasms, assuming that they had universal application. Neither a hermit nor a mystic of one of the stripes that

In school he had occasionally been called “The Judge,” yet one of the appealing paradoxes about Thoreau is how seldom this offish individualist and “solitary” lived or even traveled alone, how close he was to his family and chatty with his neighbors, how repeatedly and obstreperously he involved himself in public controversy. A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers is about a lark of a trip he enjoyed with his brother John, floating and ruminating in a fifteen-foot dory, when Henry was twenty-two. Cape Cod , although rather more somber, recounts his impressions while walking the beach and the scrublands on three brief, almost impromptu jaunts to the Cape ten or fifteen years later, twice in the company of Ellery Channing, when he was much concerned, in any case, with the plentiful anecdotes that he gleaned from the inhabitants. His journeys to Maine in 1846, 1853, and 1857 bracketed his walks on the Cape and were planned more ambitiously, as if carrying a heavier significance. They were strenuous warm-weather paddles and hikes made always with a paid guide and at least one additional companion—on. the first trip, altogether a party of six. Thoreau, as we read him, seems like a personable, vigorous Harvard graduate who, after trying to teach school and a stint in his father’s pencil-manufacturing business, had realized that his only wish was to become a writer and had set out to do so. As on the Cape, his professional purpose was to write thoughtful, descriptive essays for such magazines as The Atlantic Monthly and Putnam’s Monthly , not a seamlessly coherent masterpiece like Walden .

This is our most commonsensical Thoreau, and his Maine guides respected

Logging was the industry, but Maine was so roomy that the Abnakis had not been annihilated or seriously embittered. The rivers saw log drives instead of flotillas of trippers, and “God’s own horses”—moose—were still abundant. Thoreau met two métis (mixed-breed) hunters who had shot twenty-two for the skin trade. A guide was needed in those days, and this is a rare episode in Thoreau’s work where we see him as an employer, paymaster (though he must have supervised employees at his family’s pencil factory too), and bourgeois Bostonian on vacation. He seems wholly natural in the role, but exults at one point that he is seventy-five miles from a road, and at another that there are still places where one “might live and die and never hear of the United States, which make such a noise in the world—never hear of America, so called from the name of a European gentleman.” Joe Polis asks after a brother who has not shown up at home for a year after going off hunting—not worried that he is dead so much as wondering where in a woods so big he is contentedly wandering. In the virgin timber the loggers like to have a yoke of oxen mount each giant stump, “as if that were what the pine had grown for, to become a footstool of oxen,” Thoreau observes. More happily, he lies listening to Polis talking in his own language to a St. Francis Indian they encounter, trying to guess their subject matter by their gestures.

“Generally speaking, a howling wilderness does not howl,” Thoreau says, but he revels in the campfires ten feet long and four feet high, with snowberry and checkerberry tea, trout and moosemeat, and talk of snapping-turtle-and-beaver meals with men who write to one another on the sides of trees. The fish in the streams below Mount Katahdin are as colorful as flowers and bite wildly. Indeed, theirs is only the fifth party of white people to have climbed it, he says—a mile high and known as Kette-Adene , “greatest mountain,” to the Indians. And although Thoreau wasn’t an exceptional woodsman—only an exceptional writer—his ebullience brimmed so high

It’s high-flown, but not a preposterous-sounding apostrophe for any reader who has hiked on barren, fog-swept terrain, and of a piece with his frequent arpeggios to Indians, “the red face of man,” who eat “no hot bread and sweet cake,” but muskrat, moosemeat, and the fat of bears. Though happy and enthusiastic in the wilderness (he hails the heroism of the first white settler’s dog on Chamberlain Lake, whose nose must take the porcupine quills for the rest of his race), he is not sentimental, but quite cool in his judgments—a freethinker first and a chum second—and pays the Abnakis the compliment of his close interest, seeming to scribble notes almost nonstop, noting even the piles of moose hair they have scraped at campsites to lighten the weight of their loads. “Here, then,” he had said, explaining part of why he’d entered these wild woods, “one could no longer accuse institutions and society, but must front the true source of evil.”

He was not a man who looked for evil, however—only for foolishness. He was primarily a factseeker and a rhaosodist, and relished announcing incongruities when no revelation was at hand. He was capable of sadness and pity as well as fanfares, but did not really believe in evil. Disappointed on his first trip to Maine by the failure of two Penobscot Indians to show up because of a “drunken frolic,” he comments matter-of-factly on their resemblance to the “sinister and slouching fellows whom you meet picking up strings and paper in the streets of a city.… The one is no more a child of nature than the other.” But Joe Polis’s intelligent assistance during the third trip made him wax transcendental in a letter to his friend Harrison Blake: “I flatter myself that the world appears in some respects a little larger and not as usual smaller and shallower

His book on Cape Cod is somewhat gloomier and more jittery. The sea is not a light subject; and he begins with the sight of dead people washed ashore from the wreck of an immigrants’ ship and mourners arriving from Boston to collect the bodies. But generally, except for those few hours atop Katahdin or at the Cape, Thoreau never knew a nature that he couldn’t trust. Nevertheless, he celebrated the idea that we “hardly know where the rivers come from which float our navy”—as did Melville, just as rapt, often as jubilant. For both, nature was the central contingency, the core question or moral event of human existence. “From the Passamaquoddy to the Sabine” (Maine to Texas), the continent is still “No-Man’s Land,” Thoreau exclaimed. At the Redwood Agency in Minnesota, at the end of his life, he even met the Sioux war chief Little Crow, who a year later was to lead an uprising in which eight hundred white pioneers were killed. But for Melville, nature encompassed the constant possibility of drowning, or of a Little Crow turning murderous, or a dose of solitude that was so strong and deep that it inflicted upon the sufferer a madness like poor Pip’s in Moby Dick .

Thoreau had no interest in the pathology of solitude and didn’t engage in marathons of living alone; malignancy of any kind did not intrigue him. And gaily competent though he was when savoring a trip to the wilderness, he never thought of staying in Maine. Quite a sociable man, he was mostly concerned with far more domesticated expressions of nature, and he was offering himself as an exemplar of how anybody could live in leisurely allegiance to it even on the outskirts of a settled community. There was some gallantry to the experiment because so many people ridiculed it. Of course, the conventional thing for a man with a taste for the woods to do was to go West; and when Walden failed to be appropriately understood beyond the circle of his friends ( Knickerbocker magazine reviewed it together with P. T. Barnum’s autobiography as “humbug”), he seems to have lost heart, or at any rate, the impetus of confidence. His most radical views had always concerned how people should live, not the idea of preserving wild places at the expense of profit and development. His ire was more aroused as he watched people hiring away their lives piecemeal than by clearcut logging, and more by what went on inside New England’s textile mills than by the smoke they spouted.

Thoreau’s was stripped down to few entanglements apart from those he had been born with, and he devoted it mainly to keeping his sixthousand-page journal based on his long afternoon walks, when he went out in search of new premonitions as well as in order to spot the phenomena of natural history in which he rooted his essays. His biography is bare bones: He visited New York City twice, Staten Island, Fire Island, walked in the Catskills and Berkshires. He never married, didn’t go to church, never voted, or drank alcohol, and smoked nothing “more noxious than dried lily stems,” said Emerson. “He had no temptations to fight against—no appetites, no passions, no taste for elegant trifles. A fine house, dress, the manners and talk of highly cultivated people were all thrown away on him.…When asked at table what dish he preferred, he answered, ‘The nearest.’ … There was somewhat military in his nature not to be subdued, always manly and able, but rarely tender, as if he did not feel himself except in opposition. He wanted a fallacy to expose, a blunder to pillory. … It cost him nothing to say No; indeed, he found it much easier than to say Yes. ... ‘I love Henry,’ said one of his friends, ‘but I cannot like him; and as for taking his arm, I should as soon think of taking the arm of an elm tree.’ ” He was a born protestant, Emerson added in the funeral oration that remains the best summary of his qualities ever written, yet “no truer American existed.” And though the circumstances of his life appear remarkably uncomplicated, he made so bold as to comment upon everybody else’s.

Emerson, speaking affectionately of Thoreau’s “endless walks and miscellaneous studies,” mentions that the pond lily was his favorite flower and his favorite tree a certain basswood that bloomed in July, whose scent was “oracular” and yet earthy. The grate of gravel under his feet disturbed his delicacy so much that he avoided the highroad when he could for a path through the woods. Thank God they could not cut down the clouds, Henry had said of the axmen then infesting New England. But Emerson believed that “great men are more distinguished by range and extent than by originality” (in an essay on Shakespeare). “The hero is in the press of knights and the thick of events.” So it was inevitable that he didn’t entirely apprehend Thoreau’s achievement. With his energy and practical ability, Thoreau had seemed “born for great enterprise and for command, and I so much regret the loss of his rare powers of action that I cannot help counting it a fault in him that he had no ambition. Wanting this, instead of engineering for all America, he was the captain

America was pounding its way to prominence as a world power and mightily engrossed in inventorying its resources. We can see from reading The Maine Woods that Thoreau was indeed a brisk organizer. Emerson perhaps conceived that he had the wherewithal to be a sort of John Wesley Powell. This Civil War hero, though left with one arm, explored the thousand-mile sequence of canyons of the Green and Colorado rivers seven years after Thoreau’s death as head of a small daredevil expedition and wrote a superb book about it; then went on to become not only director of the U.S. Geological Survey but also the first director of the U.S. Bureau of Ethnology. The vigor, pleasure, and breadth of curiosity Thoreau exhibited in Maine give at least a hint of how successfully he might have pursued such a dashingly nineteenth-century type of career if he had wanted to. Frederick Law Olmsted, the landscape architect who designed New York’s Central Park and many other parks from the late 1850s on, and who probably contributed more pleasure to the public than any other American artist has, is another example of uncloistered intellectuality. So are John James Audubon, who died in 1851 after writing a vivid journal of his travels as well as painting an encyclopedia of Creation, and George Catlin (1796-1872), who wrote about the vanishing Indian tribes almost as brilliantly as he painted them. John Muir (1838-1914) walked about as far as any American except the original mountain men and virtually founded the conservation movement here. Francis Parkman graduated seven years behind Thoreau at Harvard, went west to live among the Sioux, published a sprightly account of his adventures ( The California and Oregon Trail ) in 1849, and immediately plunged into his life’s work, the seven-volume history France and England in North America , which for scholarship and stylistic and dramatic panache remains a benchmark in American historical writing.

But Emerson, in complaining of Thoreau’s lack of vocation, was partly addressing his own dilemma. America since Jefferson hasn’t really had a national intellectual, and, like the skeptic Henry Adams, Emerson often wondered what he himself was—what he should do. He was as rapturous a writer as Thoreau, although possessed of a more comprehensive versatility and more temperance in his passions. He wrote an insightful, delightful book on English Traits and others on Representative Men and The Conduct of Life , and the titles of his many essays bespeak his aspirations: “Love,” “Friendship,” “Heroism,” “Prudence,” “Intellect,” “Art,” “Experience,” “Character,” “Politics,” “The American Scholar.” However, Thoreau tended to address a number of themes simultaneously.

I brag for humanity,” he had written in Walden , and his bold irreverence, his self-assurance and certainty that nature was the central theater of life, carried it off. Without Emerson, fourteen years older, to encourage and champion him, his life would have been far more problematical and threadbare. Reading the chronology of his life, with its edgy penury and fits and starts, what seems remarkable is not how little but how much he wrote. His famous, cocksure pronouncement that “the mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation” is a dubious proposition—yet wasn’t his? Well, no, it wasn’t. He had set as his principle that what he thought—not just how he lived, but what he thought —mattered surpassingly, and that one man operating alone with no resources except his eyes and ears, his powers of logic, intuition, association, and language, could be pivotal in the meritocracy of the mind. He’d been a wall plasterer, chimney builder, apple tree grafter, had paid his dues as a walker and canoeist, had slept sometimes in huts or on the ground, and made no fuss about his college credentials. (“Let each sheep wear his own skin,” he said, when asked whether he wanted a sheepskin diploma.) And what still makes him uncannily appealing is not just his eerie contemporaneity of spirit as he writes about Cape Cod, Maine, or Walden Pond, but his assumption that all speculation is open to him, that no prevailing opinion can stand against plain common sense.

Transcendentalism was eclipsed by a century’s worth of literary realism in the aftermath of the Civil War, but not Thoreau. Most freewheeling essay writing in America on any subject derives from him, and that’s because he was exact, tactile, and practical in what he said, despite being a romantic. The twentieth century’s horrific wars didn’t crush the force of his sensibility for readers either, though one can argue with his aphorisms. Indeed, we’re “constantly invited to be what we are,” as he said. Yet for the rest of us the choice may embrace contradictory things: true-blue husband and yet romancer of women; indefatigable mother and yet a workaholic lawyer; lover of the city, but lover of the ocean. Thoreau never appears to have considered that anybody he was writing for might be any different from him—might want children, for instance, or might love sumptuous food and sensual alliances and volleys of conversation as well as piney woods and loons calling. “Fire is the most tolerable third party,”

The death of his brother John from lockjaw in 1842 had propelled Henry into a nervous collapse with psychosomatic symptoms, and the execution of John Brown seventeen years later afflicted him similarly, so he was clearly a vulnerable man, not impervious to ordinary emotions. But he had few complicating cross-loyalties and gave no hostages to fortune. He believed that life was for exulting and for self-invention; and, walking out of doors about four hours a day (buttering his boots to waterproof them), using his “Realometer” on what he observed, or inspecting the beautiful patterns of fern leaves and of the rainbow tints of clamshells in the dark mud of rivers while smelling the “raspberry air,” he lived enviably. One reads Thoreau for his foxy grace and crystalline precision, his joyful inventories and resilient spirits. Like any good naturalist, he believed that human nature is part of nature, not set aside from it, and his attention did not intensify when he was looking at human behavior instead of at wind riffling a lake. He had consummate faith that integrity and direct speaking would carry the day —that if he spoke his mind it would turn out to be something fresh and forever. And nature repaid his faith by making that true.