Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Summer 2017 | Volume 62, Issue 1

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Summer 2017 | Volume 62, Issue 1

Its size alone no doubt would have been enough to guarantee the Statue of Liberty affection right from the start in 1886, the year it was completed. Bigger was surely better in the eyes of most American beholders in that expansive era. When young Theodore Roosevelt of New York, a candidate for mayor the same year, affirmed that big things were in the spirit of the times and a fact of American life, he was addressing a small-town Fourth-of-July crowd in the Dakota Territory, but he could have been speaking for almost anyone, anywhere in the country. “Like all Americans, I like big things,” he said, “big prairies, big forests and mountains, big wheat fields, railroads, herds of cattle, too-big factories, steamboats, and everything else.”

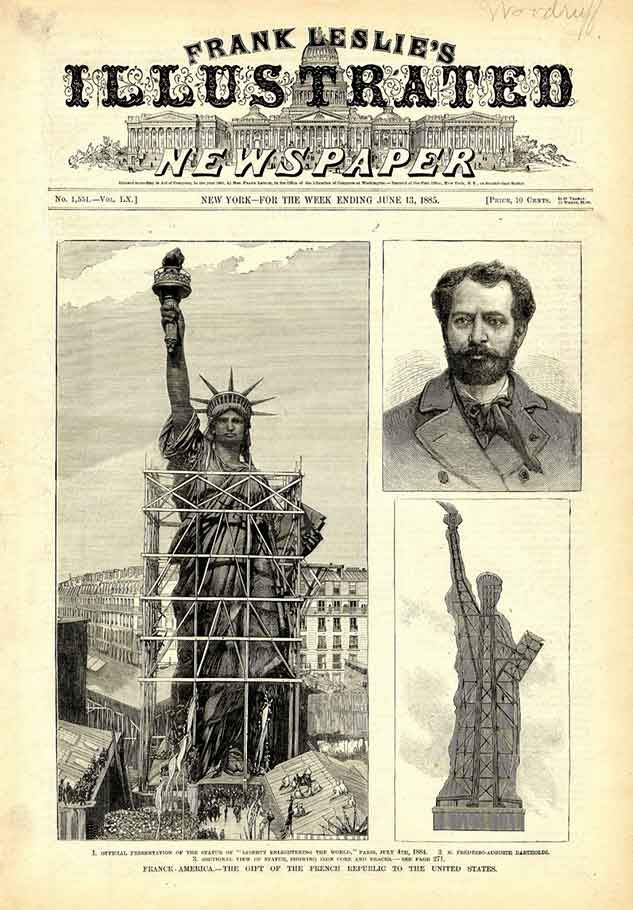

Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, the resolute genius of the great work, observed in a letter home, “Everything is big here - even the peas. . . .” As a Frenchman, he preferred his peas small. He also had some difficulty liking Americans, who, by his lights, were deficient in taste and charm. Still, for a land of such expanse, he could envision only a statue of “colossal proportions,” of “extraordinary proportions.”

At the time of completion, the statue was not just the largest ever built but the tallest structure of its kind in the world. And the vital statistics still seem fabulous. From its toe to the tip of its upheld torch, the statue is 151 feet tall. Counting the pedestal, it rises 305 feet above the tide. Its head measures 10 feet from ear to ear, its nose a good 4 feet in length. It weighs 450,000 pounds, or 225 tons, its sheathing of hammered copper accounting for nearly half of that. Inside, the route from the top of the pedestal to eye level is a steep climb of 154 steps, the same as a twelve-story building. The fact that it stands where it does, taking the winds of New York Harbor full force in all seasons, is testimony to an internal design far more ingenious and important as a feat of structural engineering than most people are aware.

Yet all that hardly explains how we feel about it, our Miss Liberty or “Liberty Enlightening the World,” as once it was known. For all the statistics, the publicity, for all we think we know about the statue, it remains an extremely elusive subject with many sides and a fascinating history.

Of utmost importance is the statue’s placement, at the gateway to America. It is emphatically a New York landmark. If it had been put up in Washington, D.C., or St. Louis or anywhere other than New York, we would not feel