Authors:

Historic Era: Era 10: Contemporary United States (1968 to the present)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Summer 2012, Summer 2025 | Volume 62, Issue 2

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 10: Contemporary United States (1968 to the present)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Summer 2012, Summer 2025 | Volume 62, Issue 2

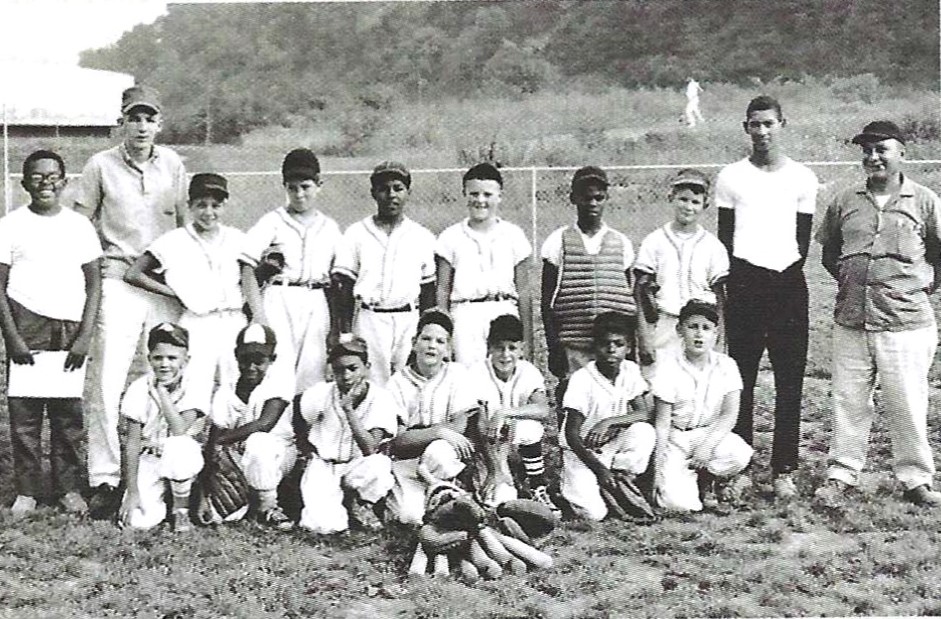

You wouldn’t know Piedmont anymore—my Piedmont, I mean—the town in West Virginia where I learned to be a colored boy. The 1950s in Piedmont was a sepia time, or at least that’s the color my memory has given it. People were always proud to be from Piedmont—nestled against a wall of mountains, smack-dab on the banks of the mighty Potomac. We knew God gave America no more beautiful location. I never knew colored people anywhere who were crazier about mountains and water, flowers and trees, fishing and hunting. For as long as anyone could remember, we could outhunt, outshoot, and outswim the white boys in the valley. We didn’t flaunt our rifles and shotguns, though, because that might make the white people too nervous.

The social topography of Piedmont was something we knew like the back of our hands. It was an immigrant town; white Piedmont was Italian and Irish, with a handful of wealthy WASPs on East Hampshire Street, and “ethnic” neighborhoods of working-class people everywhere else, colored and white. For as long as anyone can remember, Piedmont’s character has been completely bound up with the Westvaco paper mill: its prosperous past and doubtful future. At first glance, the town is a typical dying mill center, with a crumbling infrastructure and the resignation of its people to its gentle decline. Many once beautiful buildings stand empty and unkempt and testify to a bygone time of spirit and pride. The big houses on East Hampshire Street are no longer proud, as they were when I was a kid. Like the Italians and the Irish, most of the colored people migrated to Piedmont at the turn of the 20th century to work at the paper mill, which opened in 1888.

All the colored men at the paper mill worked on “the platform”—loading paper into trucks until the craft unions were finally integrated in 1968. Loading is what Daddy did every working day of his life. That’s what almost every colored grown-up I knew did. Colored people lived in three neighborhoods that were clearly demarcated, as if by ropes or turnstiles. Welcome to the Colored Zone, a large stretched banner could have said. And it felt good in there, like walking around your house in bare feet and underwear, or snoring right out loud on the couch in front of the TV—swaddled by the comforts of home, the warmth of those you love. Of course, the colored world was not so much a neighborhood as a condition of existence. And