Authors:

Historic Era: Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

October/November 1986 | Volume 37, Issue 6

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 8: The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

October/November 1986 | Volume 37, Issue 6

For hundreds of years, ships of war were of wood, moved by the wind. Their long-range weapons were simple cannon, while at short ranges, with ships locked alongside one another in deadly embrace, the sailors used cutlasses, sabers, pikes, and small arms. The strategy of sea power consisted of maneuvering, out of sight and beyond knowledge, into position where the power of the guns and their trained crews could become decisive. Before Trafalgar, as before all his battles, Nelson kept himself informed of the enemy location and movement through his scouting ships (of which he complained he never had enough). Villeneuve, commanding Napoleon’s fleet, knew the British were nearby, and hoped to avoid meeting them, but in fact had no idea of exactly where they were or what Nelson’s strategy might be. When the day of battle dawned, England’s enemy could not escape. Disaster, in the form of a concentration of British sailing battleships, leaped out of the sea and fell upon the hapless French and Spanish on October 21, 1805. Trafalgar determined Europe’s course for a century.

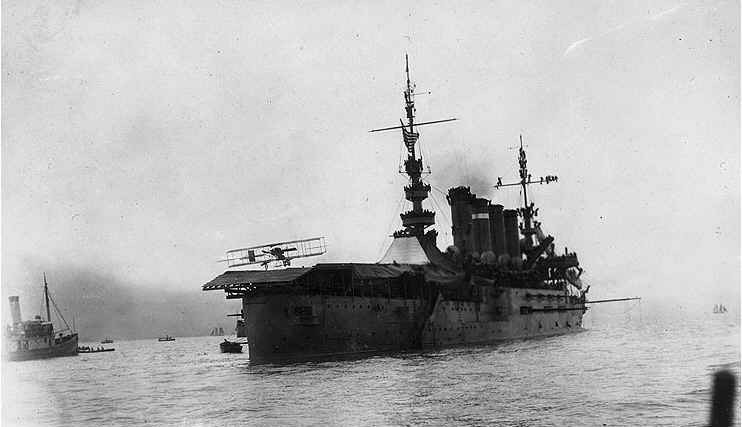

Not for 137 years, until Midway, did a naval battle have such a world-shaping effect. In the meantime, the Industrial Revolution had increased the capabilities of man a thousandfold, and those of his warships by at least twice that. Ships of war changed more in this short period than in all of naval history. It was then that the armored steam-powered battleship as we know it today developed, the first one being the little Monitor of Civil War fame. By 1940, its successors had become the epitome of impregnable force at sea. But during all its history, the battleship seldom was engaged in actual battle. It performed its function more through the majesty of its image than through the effectiveness of its weapons. These were still limited to the range of man’s vision on the surface—to the range, in other words, of guns. Meanwhile, the reach of forces had gone much farther. Despite its aura, the great fort of floating steel never really justified its existence by the conclusive Trafalgar-like combat for which it had been created. Other, smaller, ships fought the battles: even Jutland was principally a battle-cruiser engagement. And, at Pearl Harbor, the battleships were merely victims.

Nevertheless, during the last half of the 19th century and the early years of the 20th, we looked on the battleship as the quintessential, primary ship of war. But after World War I, the battleship began losing this distinction at an ever faster rate. Beginning about 1930, the men in charge of the Navy, still in romantic thrall to the