Authors:

Historic Era: Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

June/July 1986 | Volume 37, Issue 4

Authors: Elting E. Morison

Historic Era: Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

June/July 1986 | Volume 37, Issue 4

Editor's Note: This is the story of the efforts of naval officers to bring steam, coal, iron, steel, and high explosives together in satisfying combination during the last century. It was a time of transformation and change when the U.S. Navy made its way from the old sailing ships of the line to the dreadnought, also known in its first American version as the Skeerd of Nuthin. What we know of all this is still pretty much what the historian Frank M. Bennett told us in 1896 in his remarkable book, The Steam Navy of the United States. But the subject is especially important today because it may serve as a latter-day cautionary tale when technology is more complicated, more powerful, and far more omnipresent than in the days of those old ships and sailors.

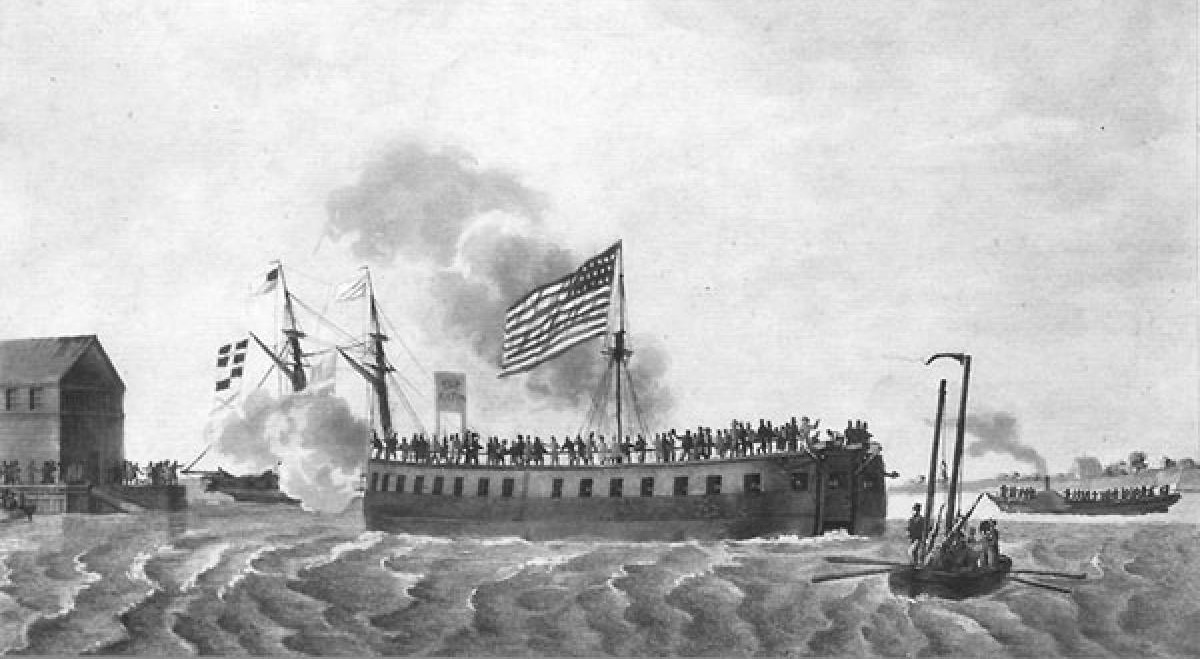

During the War of 1812, Robert Fulton persuaded the president and the Congress to build the Demologos, as the first steam warship in any navy. Because the war ended before this “steam battery” actually was finished, she never engaged in any hostile action. Still, in her subsequent trials the ship not only “exhibited a novel and sublime spectacle to an admiring people” but also demonstrated her ability to maneuver effectively in “defense of ports and harbors.”

The Congress was very impressed. In 1816, it provided for the “ gradual increase of the Navy” over the next six years by authorizing the building of three similar vessels. The word gradual was interpreted liberally. Almost twenty years later the secretary of the Navy found it necessary to ask the Board of Navy Commissioners to take “immediate steps” to fulfill the congressional intent. Officers, puzzled from the beginning by what to do with a steam battery in time of peace, had resolved the matter by doing nothing; for the rest of her life the Demologos was used as a receiving ship tied up at the Brooklyn Navy Yard better prepared to act than in 1816.

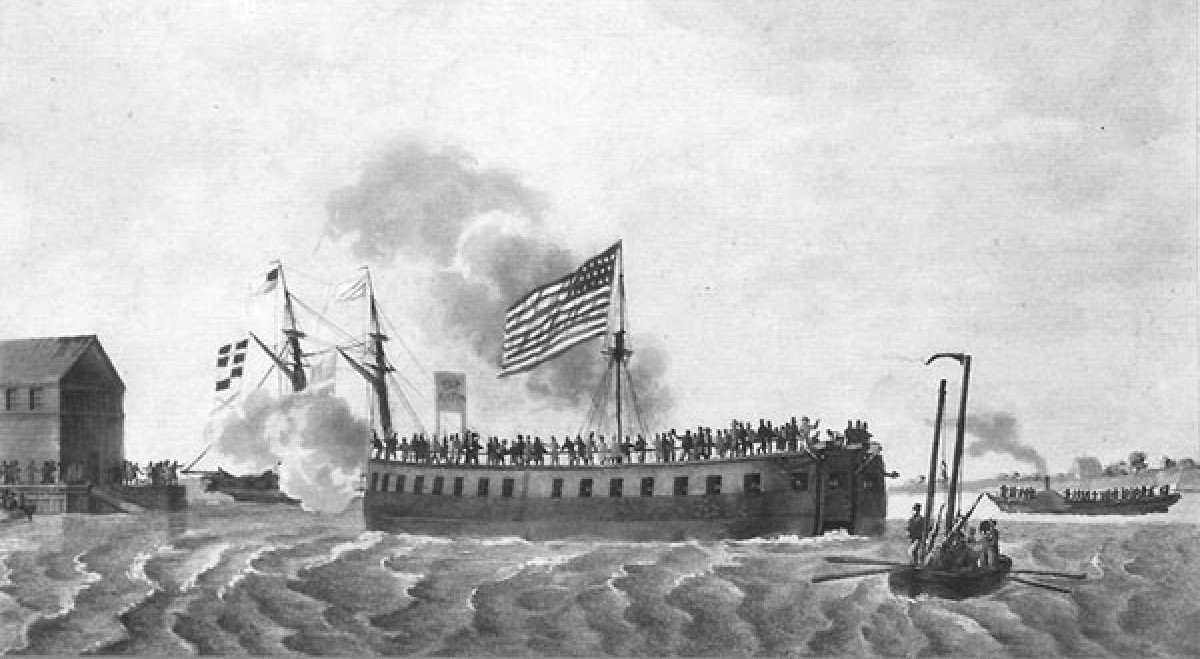

As a start the board advertised in several newspapers for someone to help by “furnishing the steam engines for the steam vessel now building.” When no one came forward in response, the commissioners explained to the secretary that “in their ignorance” they had probably not made clear what they were looking for. In time word of this ill-defined opportunity got about, and someone recommended a man named Charles H. Haswell. He appeared before the board and impressed the members by the excellence of his knowledge, his testimonials, and the elevated tone of his general conversation. In the end the board members strongly urged the secretary to appoint him, while shrouding their approval in the kind of opaque prose designed to get bureaucrats

The secretary interpreted this message to mean that the board probably could not find anyone better qualified. He probably was right. Charles Haswell, after his early schooling, had entered the shops of the great French-born engineer James Allaire, where he had learned all there was for anyone to know at the time about how to put steam engines together. So on February 19, 1836, Haswell was directed to prepare working drawings of boilers to be installed in the steam warship then building at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. He was to perform this service within sixty days in return for a payment of $250. Six months later Haswell was appointed chief engineer to supervise the design and construction of all the machinery that went into this new ship that was to be called the Fulton. He was 27 years old, and he was the first engineer to be appointed to the U.S. Navy.

If the technical universe that Haswell then entered was not quite a vacuum, it nevertheless was little more than an odd jumble of bits and pieces that no one knew much about or what to do with. If it was a ship’s hull, it could be built of wood or of iron. If it was a gun, it could be made of iron or perhaps of steel and it could be a smoothbore or some other kind of barrel not yet clearly defined. If it was a propeller, it might have two, three, four, or six blades or, better still, be a paddle wheel. If it was an engine, it might use either high- or low-pressure steam and the cylinders could vary from a nineinch stroke and a thirty-six-inch diameter to a thirty-six-inch stroke and a sixty-five-inch diameter, and it could be connected to do work in any number of elaborate ways.

For 16 years, Charles Haswell helped the Navy sort out these confusing quantities. He taught himself a great deal through that hands-on experience that is so highly recommended and so rarely obtained today. In the 1840s, it was usually the only way to learn. When Haswell designed the boilers for the Mississippi, for instance, he went to the mold loft and laid out the size and shape of each plate. From the knowledge he acquired by such means, he eventually built a series of substantial, long-wearing, and, for the period, reasonably efficient marine steam plants. He also learned along the way that the power in engines, when let loose among people who neither understood nor respected

When Haswell was the only engineer in the Navy and first went to sea in charge of the engines he had built for the Fulton , no one knew where to put him in the ship’s company. After a good deal of debate, it was decided that he should dine in the wardroom with the other officers, whatever view was taken of his engineering duties, because he seemed a man of some background and his father had been a member of the British diplomatic service. From that day forward, Haswell worked hard to define the duties performed by engineers, to establish tests of competence, and to provide those selected with an appropriate place in the structure of naval society. And his efforts bore fruit. Congress, in 1842, passed an act establishing a corps of engineers—then about twenty in number—under the direction of a “skillful and scientific engineer-in-chief.”

In obtaining this legislation, however, Haswell had received significant assistance from a man named Gilbert L. Thompson, a lawyer and rather dashing man-about-town who knew how to influence the political process. Haswell considered Thompson a “benevolent and influential gentleman” interested in the cause “simply because it was right.” Then, after the act had been passed and the corps of engineers established, the secretary of the Navy appointed none other than lawyer Thompson as the “skillful and scientific engineer-in-chief.”

Thompson came to his new office with an idea for both concealing the smoke and increasing the draft of a steam engine. What he had in mind was to run the smoke pipes through the housing of the paddle wheels where the “centrifugal action of the [turning] wheels would … force air up through the pipes.” He took this idea to Haswell, who had supervised the design and construction of the machinery for the Missouri . Haswell said the scheme was absurd and resisted it vigorously. Thompson insisted on a test and ordered the Missouri modified in accordance with his specifications. This was done in the spring of 1843.

When the changes had been made, Thompson invited members of the president’s cabinet to attend a demonstration of how his new scheme worked. As it turned out, nothing worked at all. The investigation that followed found Charles Haswell to be the source of all difficulties: he had not used “sufficiently inflammable material in lighting the fires.” Haswell was relieved of his duties until more thoughtful heads prevailed and recommended that he should return to the Missouri for her voyage to the Mediterranean—if he would apologize for not having used more volatile stuff to light off his boilers. When Haswell replied that he would “rather suffer injustice from another than be unjust to myself,” he was reassigned

His appointment as engineer in chief did not eliminate all future problems; the second incident had to do with the San Jacinto. She was one of four “war steamers” authorized in 1847 by Congress and the only one to be driven by propeller, instead of by paddle wheels. A board composed of line officers, naval constructors, and Haswell himself was appointed to determine the ship’s characteristics. After a good deal of discussion, the board specified that the San Jacinto should be built of wood; that the propeller should not infringe on any existing patents; that to reduce the length of the unfamiliar propeller shaft, the engines should be placed in the extreme afterpart of the hull; and that to avoid putting a large hole through the sternpost, the opening for the propeller shaft should be located twenty inches off the center line of the keel. Haswell disagreed with every one of these recommendations and argued long and hard against them. But, in the end, he had to yield to the other board members.

And in the end the ship was no better than he thought it would be. The machinery placed so far aft was necessarily in so small a space that oilers, firemen, and engineers had a hard time getting in to tend it. The propeller—conceived in an effort to get around patents that covered the design of lightweight screws—became a monumental wheel that weighed seven tons. Finally, to avoid that hole in the sternpost, this huge propeller not only was set twenty inches to one side of the rudder but also was projected two feet behind it, thus becoming what Bennett termed “manifestly a menace to the safety of the ship.”

Word of these things began to make its way around even while the ship was building, and the opinion grew that Haswell had made a “fearful botch of his designs,” and finally he was relieved of his duties as chief engineer of the San Jacinto.

What followed has no real place in the present discussion; its meaning, as F. Scott Fitzgerald said about something else, was only personal. But it does not seem fair to Charles Haswell or consistent with the laws of proper narration to leave him in the limbo of waiting orders. So, it may be said that when the ship was ready for her maiden voyage, he was ordered back to her as chief engineer.

But Haswell did not want this

Haswell wrote to the senior Navy commissioner to say that he now would have to resign from the service for reasons of health. The commissioner dissuaded his old friend from this action by asking him to return to the San Jacinto for her maiden voyage to the Mediterranean on the condition that if, on reaching Gibraltar, Haswell still was in failing health, he would, on the promise of the Secretary of the Navy, be invalided home. Haswell agreed, but only three days out on the voyage he had to be put on the sick list by the ship’s doctor and relieved of all duties. When the San Jacinto arrived in Gibraltar, Haswell asked the commanding officer of the station to detach him from his ship and send him home, in accordance with his agreement with officials in Washington. When the commanding officer replied that he had no authority to do this, Haswell left the San Jacinto without orders and returned to the United States.

For taking matters into his own hands in this way, Haswell was removed from the naval service in May of 1852. Seven years later, the president asked the Senate to confirm the reappointment of the man who over the course of sixteen years in the Navy had designed, built, and operated much of the machinery for its early steamships, who had been the moving spirit behind the creation of the Navy’s corps of engineers, who had drawn up the general order that defined the responsibilities of engineers (which remained a Navy manual for the next fifty years), and who had written the “Engineers’ Bible,” which stayed in print for seventy years. But the Congress adjourned before taking action on the president’s request. It is pleasing to report, however, that Haswell set himself up as a consulting engineer in New York City, where he remained for the next fifty-five years, serving a distinguished body of clients, public and private. He died, still working, ten days short of ninety-eight years of age.

Much of Haswell’s experience can be taken as confirmation of the fact that life from time to time does indeed imitate H.M.S. Pinafore. Yet beneath all those comic turns in Haswell’s career lay the hard truth that in those days it was very difficult to build a steam warship. First, those engaged did not know enough about the new engines and materials they were working with, and

The endeavors of the inventor Charles Goodyear are an exaggerated but suggestive example. Goodyear had a “firm belief in the future of rubber,” and for years he sought ways to turn raw rubber into a stable commodity. He coated it, treated it, mixed it, and kneaded into it anything that came to hand. Then one day, in the heat of an argument with friends, he happened to drop a globule of the current mixture he was holding in his hand onto the top of a hot stove—and found that he had discovered “vulcanization.”

The hit-or-miss method of inquiry was inefficient, but given the state of the art, it was perhaps the best way to proceed. It was natural, therefore, to apply it to the construction of new devices, to use what you thought you knew to make things—a propeller, a boiler, a gun, a whole ship—to see if these things would do real work. This was understood to be a down-to-earth approach and was called practice. It may also have been the best way to proceed at the time, but it had its grave defects.

For one thing, practice required a great deal of time and money. During Haswell’s time an inventor named E. N. Dickerson had an ineradicable faith that the laws governing the expansion of gases could be directly applied to the design of steam engines. It took nine years and the construction of three new ships to demonstrate that Dickerson didn’t know what he was talking about. For another thing, practice was dangerous. Captain R. E Stockton made for the Princeton a great gun—the “largest piece of wrought iron in the world.” On discharge it blew up, killing the secretary of state, the secretary of the Navy, the sometime chief of the Bureau of Construction, a member of the Congress from Virginia, a Mr. David Gardiner, and a servant of President Tyler.

And for yet another thing, practice was intellectually unproductive. Lt. W. W. Hunter thought that a fully submerged paddle wheel mounted horizontally beneath a ship’s hull would be a good thing. Three new vessels and six years later it was finally proved to be no more than a very inefficient centrifugal pump—a sort of churn. There were countless sterile occasions of this sort when the search for what might work degenerated into discovery only of what didn’t. As with all the others then engaged in mechanizing human activity, what the Navy needed was some effective control over the impulse to run almost anything up the flag-pole to see if

In the years immediately preceding the Civil War, the engineer John Ericsson gave some useful demonstrations of how this might be done. His process was a form of instruction in a novel field—the ways in which a proper concept of experiment and a judicious use of theoretical explanation could be applied to the making of new things.

Such abstract matters did not appeal very much to the available student body. Most of the down-to-earth, hard-nosed engineers considered rational experiment a doubtful exercise or, worse, a dilettante’s diversion. Such views made John Ericsson, who was never an easygoing man, absolutely exasperated. Carried to their logical conclusion, he said, they suggested that “experimentation should be conducted only by those who are incapable of constructing something.” The point of all his own experimentation, Ericsson said, was “to ascertain facts and effects, for guidance, in future practice,” so that new technical solutions could be derived from solid information and fuller understanding.

Time and again in making his new devices for the Navy, Ericsson demonstrated the effectiveness of this way of going at things. For example, he took seriously the views of those old salts who objected to steam warships on the ground that their paddle wheels would be “torn to pieces by exploding shells,” just when they were most needed. But he suggested that it was better to change the wheels than to give up the ship. So he designed a “rotary propeller,” determining the size and twist of the blades by a “geometrical construction.” Then, he built from “theoretical calculation” a “small engine” for “imparting motion directly to the screw propeller shaft.” And then, he built a small boat about two feet long that was powered by the engine and propeller he had designed. This he took to a large circular cistern, a public bath, beside which he placed a boiler. When he fed steam from this boiler into the engine in the boat, the little vessel started on a trip around the cistern at a speed of three miles an hour.

This was the experimental stage in which he confirmed his “theoretical calculations” and acquired the information necessary to build, two years later, an “iron screw steamer” tugboat. Five years after that he designed all the machinery for the USS Princeton, the first propeller-driven steam warship in the world.

The other significant figure in this period of engineering progress, Benjamin Isherwood, was a man Ericsson didn’t like very much—indeed, at all—but he did a great deal to substantiate the validity of Ericsson’s method. Two decades Ericsson’s junior, Isherwood was a member of the first class of

Starting at the other end of things from Dickerson, Isherwood began with actual operations of engines in ships at sea, tracking the distribution of steam throughout the whole propulsive system and carefully measuring gains and losses of energy in the various parts of the system. In the course of a decade he built up a comprehensive record of all his observations. Then he turned the warship Michigan into a laboratory to study the behavior of steam in a series of controlled and changing conditions. From these prolonged exercises, he acquired the evidence he needed to establish the optimal length of the cutoff—the proper amount of steam needed to obtain maximum efficiencies.

This evidence also gave him the information he needed to modify the hypotheses having to do with the expansion of gases, in effect creating a new theoretical scheme for the design of steam power plants, lsher wood published the fruits of his labor in Experimental Researches in Steam Engineering in the early 1860s. The two volumes were translated into six foreign languages and became for several generations a model for further researches.

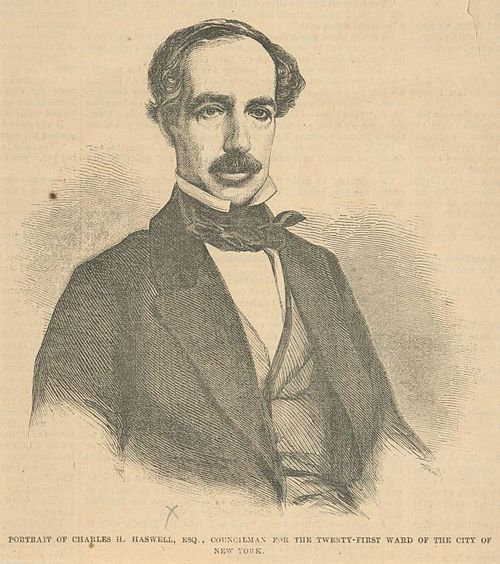

Both Ericsson and Isherwood left behind monuments to their ways of going at things. Ericsson, as all the world knows, made the Monitor, which changed forever the character of naval warfare. Isherwood, in the Civil War, built six hundred steam plants, unsurpassed in the efficiency and reliability of their performance, for the ships of the United States Navy. And toward the end of the war, he built the Wampanoag, a ship called at the time “faultless in her model and, as a steamship—the fastest in the world” and regarded by the great marine engineer George Melville fifty years later as a “magnificent SUCCESS in every way—really in many ways the greatest success as a steam war vessel that the world has ever known.”

Ericsson and Isherwood were among the founding fathers of a process now called research and development. R&D combines

But for a long time the Navy did not benefit from the process that its engineers had played such a part in developing. Between 1865 and 1881 nothing moved. After the Great Rebellion, the country was sick of war. It was a period of financial panic and hard times. In spite of the presumed lessons of the recent hostilities, there was a great deal of confusion about what a navy was supposed to do—protect harbors, destroy other nations’ commerce, guard its own merchantmen, simply show the flag. And whatever a navy did, it ought, in the judgment of a large number of naval officers, to do it with sailing vessels. These officers were hoping, as other people do, to retain an understandable order in the screwed-up scheme of things. Their feelings were bulwarked by the influence of those who were looking for the cheapest possible way to maintain the integrity of the Shield of the Republic.

Given all this it was natural that, for all her “magnificent success,” the Wampanoag, like the Demologos before her, should be turned into a receiving ship (before she was sold out of the service), because no one knew what to do with her in time of peace. Her passing was a striking demonstration that no one at the time was quite clear about what to do with any of the ships on the Navy list. Many of them were therefore left to a gradual deterioration at their moorings. By 1880, as the House Naval Affairs Committee discovered in that year, most of the warships in the fleet were no longer “capable of firing a gun.”

In this stagnant atmosphere strange ideas developed and stranger decisions were taken. Someone came up with a training manual on the art of repelling boarders. It was said by some that there was no point in armor plate; it was believed by others that the ram would become the capital ship of the future. And there was always wood and sail. At one point, a Navy board recommended to the secretary that ten vessels should be built of “live oak frames” because there was a “large supply of suitable timber at present on hand in Navy Yards.” At this time, also there was a general order that “all naval vessels” built thereafter should have “full sail power.” And a year later, Navy regulations stipulated that steam should be used only when “absolutely necessary.”

In 1877, the secretary of the Navy, George Robeson, summarized the nature of the whole period in a report that concluded with the thought that “we should congratulate ourselves on the fact” that the United States had not, “like other maritime nations,” been building fleets of “armor plated, gun bearing vessels.”

The other maritime nations were indeed doing remarkable things in the years from 1860 to 1880. They had made astonishing improvements in many parts of a warship—hulls, armor, metals, boilers, engines, propellers, guns. Those parts may not yet have fitted very nicely together in completed ships, but the activities of these other nations had produced a true revolution in naval architecture.

These alien developments finally bestirred the United States from its self-congratulatory torpor and forced it to redefine the naval reality. A variety of special interests in Congress, in industry, and in the Navy conspired to obtain legislation in 1883 authorizing the construction of four steel vessels. This was the historic White Squadron, regarded ever since as the material manifestation and shining symbol of the New Navy. It was also a demonstration of the psychic pain and practical difficulties of transition. All the ships, though propelled by steam, were rigged for sail. The three warships (the fourth was a dispatch boat) had thick main decks of steel and were called protected cruisers—but there was no armor plate around the hull. The Chicago , which was the only one to reach the designed speed, had a boiler arrangement “familiar in the American backwoods as the generator of power in sawmills.” There was continual trouble in the building of these ships, and their construction was taken out of the hands of the original contractor. But, all in all, the White Squadron was a reassuring symbol of things to come and a very important first step in the new direction.

One good consequence of the experience with these ships was the conclusion that it would be useful to find out more about what other maritime nations had been doing. When the Charleston was authorized in 1885, an American officer, then in England, was told to look around the British yards to see if he could find some plans that would fit the general specifications of the vessel. At Sir William Armstrong’s firm in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, he found the drawings for a warship the company had built for Japan. He purchased them and brought them back to the United States. Here, it was discovered that the engines were a composite of machinery that Sir William had built for the ships of three different nations; and it was further discovered that the separate parts of this composite failed “to agree with each other as to proportion and location.” From such experiences it was soon learned that a better way of achieving

In the years that followed, there were more than enough developments to keep the Navy officers busy. The gradual recognition of the uses of experiment and the growing body of theory was making itself felt throughout American industry. Using these resources, the New Navy constructed a series of ships that were successively larger, faster, and more powerful than their predecessors. But a major problem continued to complicate this progress. Advances in the various components of a warship—propulsion systems, building materials, hull designs, and guns—made it ever more difficult to bring all these changing and interacting components into an integrated whole that worked.

Changes in gun mounts, breeches, and elevating and training gears, for example, had made possible great increases in the rapidity of fire. But for a considerable period it proved impossible to devise machinery that would supply ammunition quickly enough to maintain the gunfire at maximum speed. Another and more striking ballistic example: The range of a 12-inch gun was in those years steadily extended. To achieve the maximum range, the gun had to be elevated. To achieve the maximum elevation, it was found necessary to cut so big a hole in the turret that four 12-inch enemy shells could enter at one time, destroying the gun, killing the gun crews, and dropping down the open ammunition hoist to explode the powder magazine and blow up the ship. Such a consequence was not easily apparent to constructors who had devoted their attention to separate parts in the system—the gun or the turret or the ammunition hoist. An eleven-year-old girl, taken around the gundeck of the newest ship in the Navy in 1900, seemed in a better position to assess the whole. She said at the end of her tour: “I thought you told me the guns were protected by armor. The armor is where the guns ain’t.”

What happened with gunnery systems happened also in the other technical spheres. The Navy was visited with all the trials and dangers both mechanical and human that attend any technological advance—from the uncontrolled flareback of a discharging gun to recurring deficiencies in a new kind of boiler; from the captain who went to pieces because he could not feel at home with the assembly of nuts, bolts, wires, and machines he was supposedly commanding to the chief engineer who found he could not manage the “new high powered triple expansion engines” and so locked himself in his cabin and cut his own throat.

So much for the technical difficulties. There was another major problem for those who were building the New Navy. Since there was no general agreement on what the ships were to be used for, it was hard to decide what kind

One way of dealing with this situation was to build every kind of ship one could think of that the new technology made possible. In the closing decade of the century, the Navy almost succeeded in achieving this end. The expanding fleet included “sea going coastline battleships,” cruisers “armored, sheathed and protected,” gunboats, torpedo boats, torpedo-boat destroyers, submarines, and, for old times’ sake, one armored ram. Four obsolete monitors were also being built.

This attempt to provide for every contingency produced near chaos. For instance, those “sea going coastline bat- tleships” were, as the description suggests, concrete examples of what can happen when the attempt is made to satisfy totally conflicting opinions simply by including all of them. As any seagoing battleship is expected to be, they were well armed and armored, but like any coast-defense vessel, they were slow, had a short cruising radius, and lacked the freeboard to fight in heavy weather in open waters, as seagoing battleships must do.

Another effort to find order and direction was based on the belief that the way out of the existing confusion was to exploit to the fullest the developing technology. This led to a continuing search for bigger, or faster, or better-armed ships—and also to some unexpected results. For instance, if it was accepted that the distinguishing feature of a battleship was its firepower, the obvious thing to do was to increase the weight of metal it could throw. As a result of technological advances, this metal could be thrown in many shapes and sizes. So, it seemed obvious that the thing to do was to include as many of these shapes and sizes as possible in a battleship. So, the New Hampshire was designed to carry four 12-inch, eight 8-inch, and twelve 7-inch guns, plus 20 three-pounders. The object was to throw a maximum amount of metal under any conditions and at all possible ranges. But in fact, the firing of a battery of guns of one caliber interfered with the firing of all other guns of different caliber, and the situation was not improved by the fact that the 7-inch guns had been placed so near the waterline that they could not be used to fight in a moderate sea. At their worst, such efforts to push the technological to an extreme produced the kind of total failure that inspired a naval officer to say: “ Kentucky is not a battleship at all. She is the worst crime in naval construction ever perpetrated by the white race.”

In sum, in the closing decades of the last century, the Navy, intellectually and materially, was at sixes and sevens. To maintain a sense of order and direction in its operations, the Navy continued to rely on past experience. When the new ships went to sea, they followed on the whole

From all this wearing confusion the Navy was at long last rescued by a kind of miracle. One year after the authorization of the White Squadron that had started the train of disorganizing events, an extraordinary man, Admiral Stephen B. Luce, had somehow persuaded the service to establish a war college. He believed that, in such a place, “by reasoning from the facts of naval history to general principles,” it would be possible to raise “naval warfare from the empirical stage to the dignity of a science.”

For a period of years, the institution thus conceived was greeted with utter indifference by most and with measured contempt by the rest. It seemed to have no probable future. The opinion of the service is well expressed by a conversation that took place in 1892. Two officers bumped into a friend on the steps of a Washington club. The friend, also an officer, was on the staff of the War College. Was there to be a session this year? they asked him. There was, he replied. “Well,” he was asked, “are you going to do anything practical?”

“What do you mean by practical?” he wanted to know.

“Well, torpedo boats, launches, and that sort of thing.”

Two years earlier, that staff officer, working at the War College, reasoning from the facts of naval history to some general principles, had finished a book called The Influence of Sea Power upon History. It had been a tremendous success, including among its readers such distinguished names as Kaiser Wilhelm II and Theodore Roosevelt. But it seems probable that none of those officers on the steps in Washington yet realized that in its pages would be found in time the blueprint for the first practical organization not only for torpedo boats and launches but for all the other naval ships at sea.

What Alfred Thayer Mahan said, reduced to its ultimate simplicity, was this: The great end of naval warfare is the command of the sea, and the means to that end are fleet engagements on ocean waters. If this is established, all the subsidiary concerns—our harbor protection, coastline defense, blockade, and commerce destruction—are made irrelevant.

Thirty years earlier, Benjamin Isherwood, brooding upon the potential of his Wampanoag, had thought of all this and had put it more succinctly than had Mahan. Isherwood had argued for the building of a fleet of seagoing “iron steam ships —clad with invulnerable armor plates, furnished with maximum steam power.” With these, he

Thirty years later, when Mahan put forward the well-argued case in support of a similar idea, he found a more receptive audience. His thesis—so carefully developed from historical facts—that the lifeblood of a nation was commerce and that the security of that commerce depended on warships acting together as a fleet—fighting not on a nation’s “hearthstone” but “beyond the threshold”—had an immediate appeal. It took some time to make its way, but it slowly got through. And as this concept of ends and means took hold, it brought order to the technology.

When it became clear, for instance, that a battleship was more than a floating battery of ambiguous purpose, that it was, in fact, an integral, maneuvering part of an organized line of battle, the backbone of the fleet, it became possible by defining its function to determine the characteristics required to fulfill that function—to determine, in other words, its appropriate form. Thus the interfering fire of mixed batteries designed primarily to increase the weight of metal gave way in 1906 to the single-caliber all-big-gun ship that could deliver far more destructive energy far more accurately.

By the same token, it then became possible to figure out the other functions to be performed when lines of battle meet in hostile engagement—the scouting and screening activities that contribute to the whole endeavor—and from there to establish the hierarchy of types —cruisers and destroyers—that made up the fleet. After years of confusion things fell into place.

As the technology moved toward a more settled structure, other less tangible matters began also to fall into place. As the importance of machinery increased, the position and influence of engineers became more clearly defined and accepted. With the progress of ballistics the place of the gunnery officers in the hierarchy of all line officers became almost, if not quite, as significant as that of a good ship handler. And the ascent in that hierarchy led through defined stages of command from destroyers through cruisers to battleship divisions and, if you were lucky, to flag rank. During these years, the Navy recovered its earlier dignity as a service sure of its intentions and at home with itself.

It is no doubt disconcerting for some historians to realize that one of the

He didn’t always get it right. He opposed, for instance, the all-big-gun ship because he felt that opening engagements at the extreme ranges permitted by the great guns would produce in the naval mind an “indisposition to close” that was in conflict with the magisterial Nelsonian dictum that no captain could go far wrong if he laid his ship alongside an enemy. But, on the whole, building his arguments on a base of the historical evidence, he said many wise and constructive things.

And now that Mahan and his works have themselves become historical facts, can they be usefully applied in the present circumstances? Some years ago, I suggested that the development of our modern Navy could be taken as a kind of parable. What the naval history of the past century nicely demonstrates is this: If you want to design and control a satisfying technological system, you must have, beyond a sense of the engineering possibilities, a clear idea of what you want to use it for.

About the time that Mahan was writing his book, Thomas Huxley came over to this country with much the same message. You have all these steam engines, dynamos, open hearths, rolling mills, and consumer goods, he pointed out, but have you figured out what you are going to do with all these things? That, he said, was the “great issue about which hangs a true sublimity and the terror of overhanging fate.”

The world has changed a good deal since then. For one thing, it has in itself become an evolving technological system. It is now within the engineering possibilities to replace the work of the hand with the operation of the robot, to colonize the outer spaces of the universe, to preempt much mental activity with an artificial intelligence, and to blow the whole thing up. But the overhanging issue still overhangs. The criteria for determining some unifying purpose and maintaining order among all these great potentials are simply not yet there. The earlier ideal of progress is insufficiently defined to serve as a controlling concept. The current overriding aim, though more precisely stated as the constant increase of the gross national product, has proved too narrow.

What seems now required is a scheme of things for human affairs as comprehensive in its statement of ends and means as were the command of the sea and the composition of the fleet for those concerned with naval

The search may well start from the recognition that people won’t know what to do with technology until they have a clearer and more distinct idea of what they are and might hope to be. When you can do almost anything with the machinery, it becomes necessary to decide first what you plan to do for and with yourselves. That new scheme of things will therefore have to include a revised list of priorities, an array of alternative satisfactions, the assumption of new kinds of responsibilities, the acceptance of self-imposed disciplines, and quite probably a new definition of what makes life worth living. It’s a tall order and will take some doing, but as the naval lesson suggests, it may be the best way to circumvent the workings of fate.