Authors:

Historic Era: Era 9: Postwar United States (1945 to early 1970s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Spring 2010 | Volume 60, Issue 1

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 9: Postwar United States (1945 to early 1970s)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Spring 2010 | Volume 60, Issue 1

Winter weather canceled the sold-out gala banquet to celebrate the opening of the International Civil Rights Center and Museum in Greensboro, North Carolina, on Saturday, January 30. But come Monday morning, glad throngs braved the cold to commemorate the day, 50 years earlier, when the civil disobedience of four young men in a luncheonette snowballed a change for America.

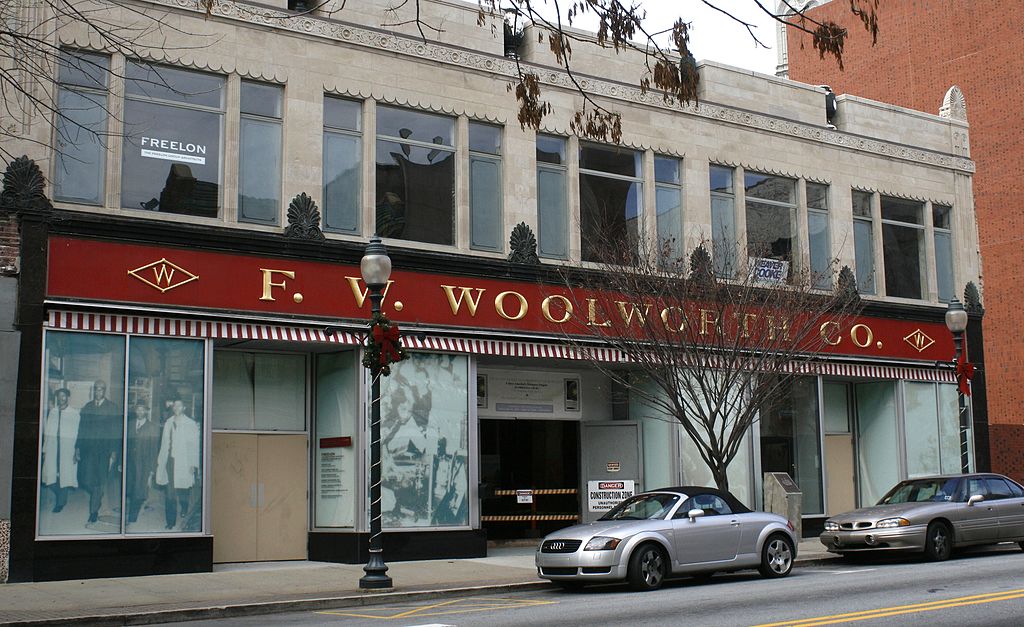

They were the “Greensboro four”—Joseph McNeil, Franklin McCain, Jibreel Khazan (then Ezell Blair Jr.), and the late David Richmond—four freshmen at the local state college, who sat at the whites-only counter at the F. W. Woolworth five-and-dime store, ordered coffee and doughnuts, and held the first sit-in protest that launched a movement felt throughout the nation.

A film in the new museum reenacts the dorm room conversation that McNeil had with his classmates after Christmas five decades ago. He described his anger at not being able to buy a meal in the depots he passed through on the bus from New York City back to school after winter break. Throughout the South (and parts of the North), local custom then maintained separate facilities for “Whites” and “Coloreds”—separate rest rooms, separate water fountains, separate restaurants (or none at all for African Americans). The young men made a plan to do something about it.

That Monday—February 1, 1960—they walked into Woolworth’s an hour before closing and bought a few things. Then they sat down at the lunch counter and ordered drinks and snacks. A clerk refused to serve them because only whites could sit at the counter (blacks had to eat standing up or take their food outside). The manager alerted police to possible trouble but didn’t try to evict the orderly demonstrators. His superiors told him to ride things out; the problem would blow over.

The Greensboro Four returned the next day and every day that week, each time joined by a growing number of other students; some followed suit at the nearby Kress five-and-dime. Within a week, a thousand peaceful demonstrators and counterprotestors were facing off.

Although some white citizens grumbled, and rumors buzzed of Ku Klux Klan retaliation, civility prevailed. Greensboro’s city officials, police, and business leaders—including the Woolworth and Kress managers—chose to break the spirals of confrontation and violence that were disrupting life in other southern cities and lifted their whites-only policy by the end of July. Sit-ins soon became a cornerstone of the civil rights movement, spreading to 55 cities in 13 states.

As Senator Kay Hagan recalled at the new museum’s ribbon-cutting ceremony, “by the end of the week, hundreds from surrounding