Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2010 | Volume 59, Issue 4

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 5: Civil War and Reconstruction (1850-1877)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Winter 2010 | Volume 59, Issue 4

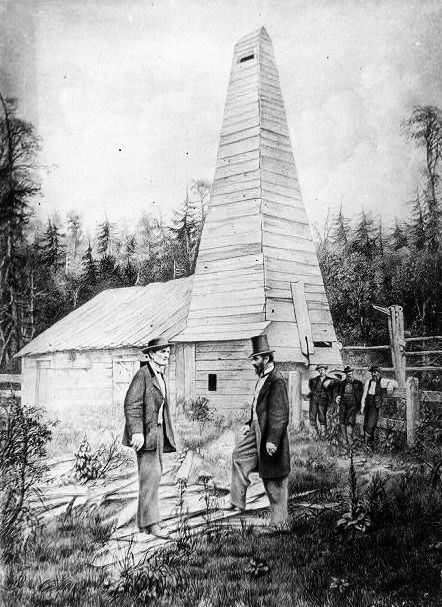

By August 1859, “Colonel” E. L. Drake and his small crew were disheartened. Few if any of the locals believed that oil—liquid called rock oil—could come out of the ground. In fact, they thought Drake was crazy. A small group of Connecticut investors had set Drake up in the small lumber town of Titusville in northwestern Pennsylvania to try this “lunatic” scheme. The work was slow, difficult, and continually dogged by disappointment and the specter of failure. After a year, the venture had run out of money, and New Haven banker James Townsend had been paying expenses out of his pocket.

At the end of his resources, Townsend reluctantly sent Drake a money order as a final remittance and instructed him to pay his bills, close up the operation, and return to New Haven. Fortunately, mail delivery to the backwoods of northwest Pennsylvania was slow, and Drake had not yet received the letter when, on Sunday, August 28, William “Uncle Billy” Smith, Drake’s driller, coming out to peer into the well, saw a dark fluid floating on top of the water.

On Monday, when Drake arrived, he found Uncle Billy and his boys standing guard over tubs, washbasins, and barrels that were filled with oil. Drake attached a hand pump and began to do exactly what the scoffers had denied was possible—pump up the liquid. That same day he received Townsend’s order to close up shop.

This event launched the American oil industry, a business that would transform the world. Had the elements not come together, and had the protagonists not possessed more willpower than reason, the birth of the industry might have been postponed another 10, 20, or 30 years.

Up until that time, Americans had lit their homes with lamps fueled primarily by whale oil. The world was running short of this commodity, and prices had reached the astronomical level of $2.50 a gallon. Finding a substitute would make a man rich.

An entrepreneur named George Bissell virtually stumbled upon the idea of drilling for “rock oil” and using it as a domestic lighting fluid. A graduate of Dartmouth College, Bissell had pursued a disparate range of jobs, from superintendent of schools in New Orleans to journalism. On his way back to the Northeast he had passed through rural, isolated northwest Pennsylvania—the back of beyond—and had come across something of the tiny rock oil industry. People gathered small volumes either by skimming it off creeks in Titusville’s “Oil Valley,” or wringing it out of rags soaked in seeps, and sold it for patent medicine. Visiting back at Dartmouth, Bissell saw a sample sent to a professor there, who said it might make a good lighting fluid. Bissell had one other flash of inspiration, supposedly from seeing the label