Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

April/May 1983 | Volume 34, Issue 3

Authors: Walter Karp

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

April/May 1983 | Volume 34, Issue 3

FOR THE WHALING MEN OF NANTUCKET , the year 1819 looked to be an especially promising one. The island’s famed whaling fleet, ravaged by the 1812 war, now numbered sixty-one stout vessels, and fresh fishing grounds had just been discovered in the equatorial waters of the central Pacific. The new grounds lay 17,000 sailing miles away in ill-charted seas, but Nantucketers routinely made voyages whose immense length only a handfulof great explorers could match. Reaching the grounds usually meant rounding Cape Horn, but Nantucketers had been doubling the dreaded Cape since 1792.

Their quarry was the sperm whale, whose peerless oil lit the ballrooms of Europe. Of the thirty vessels leaving Nantucket in 1819, fifteen were bound for the new grounds. One of them, the whaleship Independence II, would discover an entire new atoll in the central Pacific. Another, the Maro, would sail beyond the new grounds and hit upon still richer grounds off Japan, thereby inaugurating Nantucket’s palmiest days. And then there was the whaleship Essex, which embarked from Nantucket on August 12, 1819, and sailed into the most harrowing nightmare in the disaster-rich annals of whaling.

The doomed bear no marks of distinction. When the Essex sailed for the southern seas, it was just a typical Nantucket whaler with a typical whaling crew. The ship was a tubby, 238-ton three-master, provisioned for a two-and-a-half year cruise, which meant quite literally that it could sail for two-and-a-half years without putting into port. Nantucket’s self-reliant whaling men disliked depending on the land, of which they were often remarkably ignorant. The two chief officers of the Essex were well-tested Nantucket whalemen. George Pollard, recently first mate of the Essex, was now, at age thirty, its captain. His comparative youth was typical; whaling was a young man’s occupation. Owen Chase, recently boatsteerer on the Essex, was now, at twenty-three, its first mate.

Outlanders in the twenty-man crew included one Englishman, one Portuguese, two Cape Codders from Barnstable, and six black men. Their presence, too, was quite commonplace. Nantucket’s ship owners, half of them Quakers, cared nothing about race. “Uncommonly heedful of what manner of men they shipped,” as Herman Melville was to put it, they wanted strong character, firm minds, and high courage in their crews. Hunting the mighty sperm whale, whose twenty-foot

For the first fifteen months of the voyage, nothing out of the ordinary occurred. There were storms, spills, bruises and smashed whaleboats—the routine hazards of the hunt. By January 1820 the Essex had doubled the Horn in the teeth of gales so fierce and seas so mountainous it had taken five weeks to make the brief passage. For several months thereafter the ship had hunted whales off the Chilean coast—the familiar “on-shore grounds”—and taken eight. Heading north off the Peruvian coast it had taken several more. The cruise was already proving successful. In October the Essex had put into the uninhabited Galápagos Islands (which a young naturalist named Charles Darwin was to visit fourteen years later aboard H.M.S. Beagle ) in order to repair a leak and stock up on the island’s huge turtles before plunging westward along the equator to the new whaling grounds.

Looking up from his work, Chase spied a sperm whale a ship’s length away making toward the bow of the Essex at a moderate pace. A full-grown sperm whale is a fearsome leviathan, growing to more than eighty feet long. Its huge, squarish head is an ugly, twenty-foot battering ram filled with one ton of precious spermaceti oil: protection for its brain when it dives into the ocean depths—as much as a mile—in search of giant squid. Chase, however, was not alarmed in the slightest. The sheer strength and size of the sperm whale makes it dangerous to hunt in cockleshell whaleboats, but of malign or hostile intent it had never given the slightest sign. “I involuntarily ordered the boy at the helm to put it hard up, intending to sheer off and avoid him,” Chase recalled in his Narrative of the Extraordinary and Distressing Shipwreck of the Whaleship Essex. (Chase’s “wondrous story,” said Melville, who chanced to read it in 1841, had “a surprising effect on me. ” Indeed it had. Without Chase’s account, Moby Dick might never

What happened next brought sheer, numbing shock. Chase’s order to sheer off from the whale was “scarcely out of my mouth before he came down upon us with full speed and struck the ship with his head.” The Essex trembled from the blow, and “we looked at each other with perfect amazement, deprived almost of the power of speech. ” Minutes later the silence was broken by a frantic shout from one of the men: “Here he is—he is making for us again!”

The impossible was happening a second time. The whale, having passed under the Essex, had turned around to attack it once more, “with twice his ordinary speed, and to me at that moment, it appeared with tenfold fury and vengeance in his aspect.” This time when it struck, the strangely malignant whale completely staved in the bow of the Essex. Snatching up a few supplies, the eight men on board jumped into a whaleboat, pulled at its oars a few times, and then sat back in silence and despair as they watched their ship, their home, their safety, slowly heel over on its side and settle softly in the vast, empty sea.

While Chase and his mates sat in their whaleboat “absorbed in our own melancholy reflections,” the rest of the crew returned from the hunt. Facing forward while the others rowed, the steerer of Captain Pollard’s boat was the first to see the grim spectacle. “Oh, my God,” he cried out, “where is the ship?” Captain Pollard leaped to his feet to look. After one shocking glimpse of the heeled-over Essex, with its masts and sails dipping into the sea, he fell back into the boat, ashen-faced and speechless. Pulling himself together, the captain called to his first mate: “My God, Mr. Chase, what is the matter?” He answered, “We have been stove in by a whale.” It was indeed what Chase was to call it: “a sudden, most mysterious and overwhelming calamity.”

The plight of the men of the Essex, shipless on the vast sea, was more than desperate. Disaster could scarcely have struck them in an area of the Pacific more devoid of islands or more bereft of maritime traffic: 0°40′ south latitude, 119° west longitude, according to Chase’s reckoning. To the east the nearest certain landfall was the coast of Peru, 2,400 miles away, but even that was out of reach, for the ocean current runs westward along the

Consulting their navigation manuals—the steward had rescued two while Chase snatched two compasses before abandoning ship—the two chief officers of the Essex were well aware that the Marquesa Islands lay only 1,500 miles southwest of them. With favoring winds and a west-running current, it was an entirely feasible voyage. To the Marquesas, however, they dared not set sail. “We feared,” Captain Pollard later explained, “that we should be devoured by cannibals if we cast ourselves on their mercy.” Poor, insular Nantucket men, so self-sufficient at sea, so ignorant of the land. The Marquesas, had they but known it, were friendly Polynesian territory, which a U.S. naval commander had actually claimed for the United States in 1813. As for their dread of cannibalism, that would prove a more grisly irony than they could possibly have conceived.

To reach safety, then, they had no choice it seemed but to attempt an immense and near hopeless tack across the southern seas. They would sail south, Pollard and Chase decided, until they reached 25° south latitude, an awesome 1,900 miles away. Once there, in the region of variable, often westerly, winds, they would make for Chile, some 2,200 miles away due east. Such was the prospect that lay before the twenty shipwrecked men of the Essex: a 4,100-mile voyage in three open whaleboats, 500 miles farther than even the redoubtable Captain Bligh had gone in the launch of H.M.S. Bounty thirty-one years before.

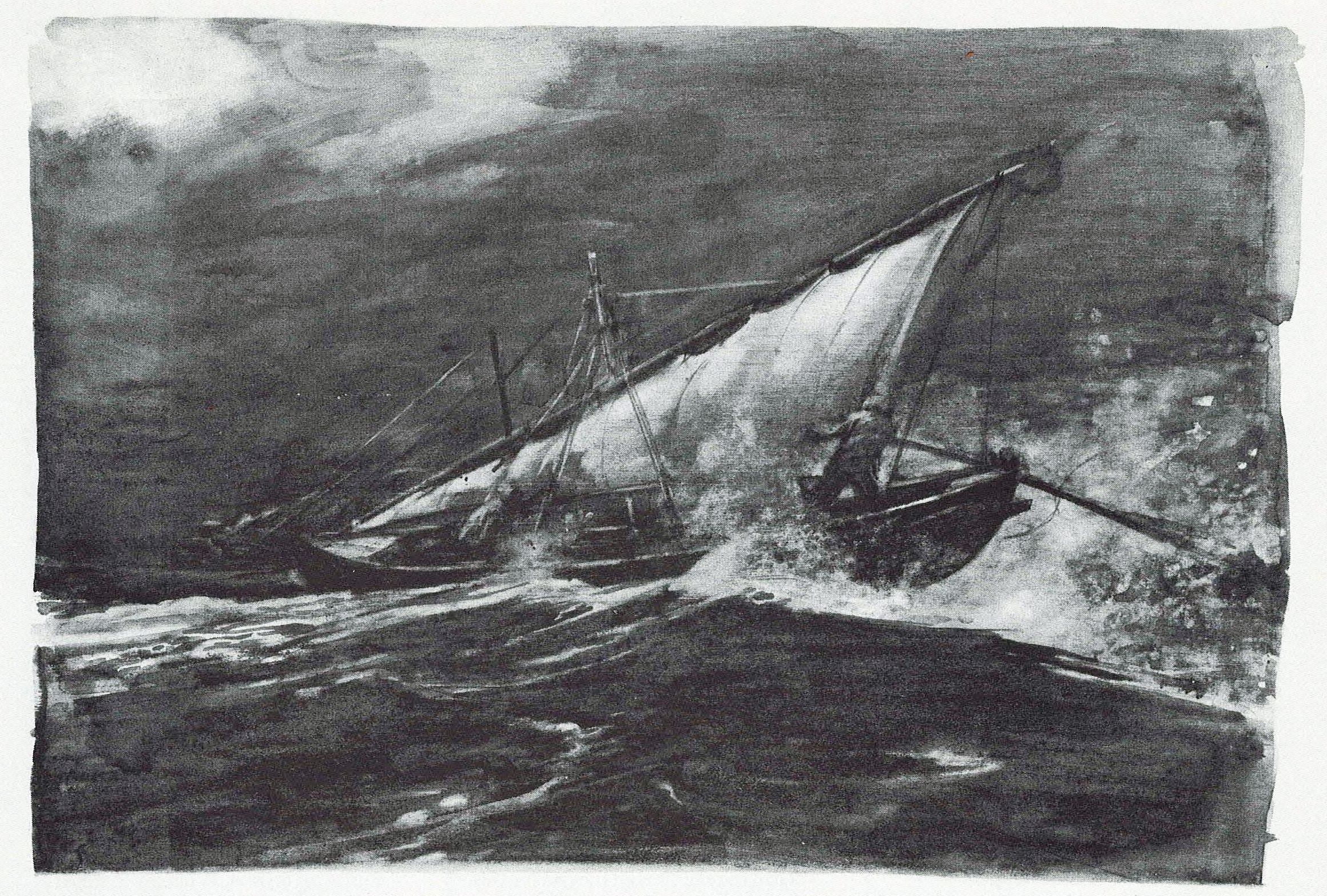

Nor did the Essex crew have sturdy, powerfully built launches to carry them through the cruel caprices of sea and wind. The Nantucket whaleboat was a remarkable seaworthy vessel, so light and buoyant it could keep its bow above “the most riotously perverse and cross-running seas,” as Melville put it. Unfortunately it was as frail as it was buoyant, a boat rudely built for easy repair, since it was likely to be smashed up by a writhing whale at least once during a cruise. All that stood between a whaleboat’s crew and the ocean depths was a half-inch of overlapping cedar planks. How such a fragile, leaky craft would fare over 4,000 miles, through shark-infested waters and tropical gales, the shipwrecked men did not care to ponder too closely.

They had, Chase reckoned, about sixty days’ worth of victuals and no means, save dead reckoning, to calculate the longitude. That night, after fastening long lines from their boats to the wreck of the Essex, twenty emotionally drained men tried to sleep, but only a few succeeded. Some wept, others railed against their singular fate, and even Chase, the most indomitable of them all, could find no rest. The memory of the “horrid aspect and malignancy of the whale” haunted his night thoughts. Not a single man, Chase recalled, had eaten a morsel of food all day. Shock and apprehension had robbed all of their appetites.

The next morning, cheered by the sun, the men of the Essex completed the final preparations for their desperate open-boat voyage. Stripping spars and light sails from the wreck, they rigged each whaleboat with a second mast, a flying jib, and two spritsails. For protection against high seas, they got cedar planks from the Essex and added six inches to the sides of their boats. There was nothing left to do, yet the shipwrecked men made no move to embark.

They were not yet ready to cut the umbilical rope that still bound them to the mother ship. “Wrecked and sunken as she was,” said Chase, “we could scarcely discard from our minds the idea of her continuing protection.” Instead, as Captain Pollard recalled a few years later, “we continued sitting in our places, gazing upon the ship as though she had been an object of tenderest affection.” The looming terrors of the immense journey before them, the thought of their frail open boats, and the sheer awesome loneliness of the indifferent sea paralyzed the men of the Essex for twenty-four hours more.

Not until 12:30 P.M. on November 22, three days after the whale had taken its mysterious revenge, did the three whaleboats cut loose from the wreck and set forth. Captain Pollard commanded one boat, Joy another, and Chase the third. In deference to its weak, patched-up condition, he had one less man aboard than the others, six to their seven.

The grim routine of their lives was quickly set. The daily ration per man was a half pint of water—one-eighth the normal shipboard allotment—and a ship’s biscuit weighing one pound three ounces—meager enough, but it would soon seem a feast. At night in stormy weather the three boat commanders performed prodigies of seamanship to keep the little fleet together. In rough seas they were compelled to bail constantly. In relative calm they patched up little leaks that seemed to spring up perpetually in their clinker-built boats.

Chase and his men had an alarming revelation of the dangerous frailty of their whaleboats before they had been three days away from the Essex: well below the water line the boat suddenly sprang a leak. With great difficulty they managed to nail a piece of planking over the hole, but everyone knew what the accident signified. One loosened nail in the boat’s bottom could doom them. “We wanted not this additional reflection to add to the miseries of our situation.” Three days later the shipwrecked voyagers discovered yet another unnerving aspect of their situation. Chase’s boat had to rush over to rescue Captain Pollard’s from the assault of a twelve-foot fish. It took several men to beat off its attack. Nantucket’s sea hunters had now become the hunted.

Beating south through the region of the doldrums, their progress was proving perilously slow. On December 8, sixteen days after cutting loose from the Essex , the three boats, according to Chase, had only reached 17° south latitude, roughly 600 miles south of the sinking, a rate of less than 40 miles per day. Once they got to the twenty-fifth latitude they could hope to make swifter passage, but the first signs of starvation were already beginning to appear: the steady weakening of wasting limbs, the griping bowels, the fitful sleep that brings not rest but tormenting dreams of savory banquets. On December 10, when a few flying fish struck a sail and landed in the bottom of Chase’s boat, the ravenous men gobbled them up in an instant, raw and alive, bones, scales, entrails, and all.

Despite the ravenous hunger and the maddening thirst, on December 14 Chase made a decision that attested to his courage, to his implacable realism, and to the extraordinary confidence that he inspired in his five comrades. That day, after calculating distance yet to go and provisions still on hand, he proposed that the rations be cut in half. Henceforth his men would have only half a ship’s biscuit per day. A few days later he cut the water ration to a quarter pint a day per man. As a precaution, Chase kept the supplies by his side and slept with a loaded pistol in his hand, but there was no attempt to steal. Under the calm leadership of the twenty-three-year-old mate from Nantucket, discipline remained firm, while the sufferings of the men increased with the passing of each wretched day.

When dawn broke on the twentieth of December, one month since the Essex had heeled over in mid-ocean, two things were apparent to Chase. First, they had completed the first leg of their journey, for they had reached the twenty-fifth latitude. Second, with the supplies on hand, they had only the slenderest chance of ever reaching the coast of Chile. Death by slow starvation, or far worse, by thirst, seemed to be their likeliest fate. Of the six emaciated wretches in the first mate’s boat, two had already abandoned hope and were sunk in apathy, utterly indifferent to their fate. Then, at 7:00 A.M., one of Chase’s men shouted, “There is land!” At that even the broken-down figures roused themselves from the stupor of death. By the sheerest good fortune the three Essex whaleboats had come upon a minute dot of an islet in the empty reaches of the southern seas. “It appeared at first a low white beach,” recalled Chase, “and lay like a basking paradise before our longing eyes.” It took four hours of sailing to reach it. It took every ounce of strength for the hunger-depleted men to crawl out of their boats and wade weakly to the shore. When they reached it, they flung themselves to the ground in blissful relief and thanksgiving. From the terrors of the sea they had, at least for the moment, a blessed surcease.

When the men began foraging for food around the rocky shore, they discovered quickly enough that their providential landfall was something less than a basking paradise. Food in small quantities they found, although many of the men were too weak to do more than crawl on their hands and knees in search of it. There were birds so innocent of men that they did not stir a feather until grabbed by the throat. There were, in addition, birds’ eggs, berries, and edible grasses as well as a crab or two in the tidal pools on the beach. The life-and-death problem was water. For hours a search party of ragged men crawled around the rocky outcroppings near the beach in search of a spring. Nothing turned up all that day. The paradise was beginning to look like the cruelest of traps, enticing desperate men to waste what little water they had while it offered them just enough food to sustain their exhausting search for more. The next day, in a state of near frenzy, the men crawled over the rocky hills, inspecting every crack and crevice, hammering at the very rock itself, in an increasingly frantic search for a freshwater spring. Once again the search proved futile. That evening Captain Pollard told his weary and disheartened men that unless they found water the next morning, they had no choice but to abandon the treacherous island and throw themselves once again on the mercy of the sea.

The following morning, after a few more hours of vain search, even Chase was ready to give up in despair. Then he heard happy cries from the beach. Someone had at last found water. “At one moment I felt an almost choking excess of joy, and at the next I wanted the relief of a flood of tears.” Henderson’s Island had hidden its treasure well. The spring of fresh water burbled from a rocky cleft on the beach itself. At high tide, six feet of sea rolled over it. Twice daily at low tide, however, it offered

For the next two days, the ragged, ravenous men foraged for food while continuing at each low tide to fill up their water kegs. On legs too weak to climb hills, however, their foraging range was severely restricted, and twenty hungry men were depleting its resources with considerable speed. On Christmas Day—their fifth on the island—not a single fresh morsel of food could be found. On that day, at a general council, the survivors of the Essex made a hard decision. It would have been easy enough to sail the boats to another part of the island and begin foraging afresh from there. Perhaps in due time a whaling ship might rescue them. After the suffering they had already endured in their boats, anything might seem preferable to returning to the sea and its terrors.

The illusion of safety, however, did not seduce them. The island’s eighteen square miles simply could not feed twenty men indefinitely. They decided to leave as soon as their water kegs were filled and their leaky boats repaired. Only three men demurred: William Wright and Seth Weeks of Barnstable and Thomas Chappie of Plymouth, England. To the certain perils of the ocean they preferred the passive misery of the semi-barren islet. What lay in store for castaways on Henderson’s Island they were soon to discover in a cave: it held the skeletons of eight shipwrecked mariners.

For the second and final leg of their voyage, Pollard and Chase now sketched out a confident course. Instead of making blindly for the remote South American coast, they intended to set a course south-southeast for Easter Island, 900 miles from Ducie and 1,100 miles from their real location. If they missed that speck in the sea, 2,000 agonizing miles would still separate them from the South American coast. With that prospect of failure in mind, perhaps, Captain Pollard wrote a brief account of the shipwreck of the Essex , put it in a tin box, and nailed the box to a tree; men hate oblivion as much as they fear death. At 10:00 A.M. on the morning of December 27, seventeen emaciated survivors once again took to their whaleboats. The three who chose land did not see their comrades off. The castaways could not bear the painful wrench of parting from those whose sufferings they had shared for so long.

The first man to die was the second mate, Matthew Joy. He had been somewhat sickly, the others recalled, ever since leaving Nantucket. His ailment had probably been minor, but after fifty days on a starvation diet, the smallest bodily frailty becomes as deadly as the deadliest disease. At dawn on the eleventh of January 1821 the mortal remains of the second mate were sewn up in his clothes, weighted with a stone, and “consigned, ” said Chase, “in solemn manner to the ocean. ” Only one other stricken man of the seventeen was to be granted that final dignity.

Two nights later, with a fierce gale blowing, Chase, at the rudder, peered through the gloom and the spray to see how the other two boats were faring. They were nowhere in sight. Heading his own boat into the wind, Chase drifted anxiously for an hour hoping to come upon them, but they had vanished completely. The men in his boat were now utterly alone, in the immensity of the Pacific. “We had lost the cheering of each other’s faces, that which, strange as it is, we so much required in both our mental and bodily distresses. ” According to Chase’s January 14 calculations, they had sailed only 900 miles eastward since leaving the island. At that rate it would take five weeks to reach Juan Fernandez. Chase, the relentless realist, refused to live by false hopes. Once again he cut the food rations, this time drastically. Henceforth, five starving men would each have to survive on one and a half ounces of ship’s bread a day.

The men were approaching a state of unbearable, excruciating misery. Painful boils broke out on their wasted flesh. The griping cramps of empty bowels tormented their waking hours, while dreams of food continued to torment their sleeping ones. From each such dream Chase himself awoke with a craving for food so frenzied that he ripped off a piece of cowhide from one of the oars and tried vainly to chew it. Too weak to stand up—standing brought on blinding vertigo—Chase and his comrades scarcely had strength left to set sails and to steer. On January 15, when a hungry shark began champing at the boat, someone grabbed a lance—a deadly weapon that had ended the lives of countless

The fickle wind, too, unnerved them. It was as variable as the navigation manual had indicated. It would blow favorably for a day, reviving hope, and then turn dead against them for two days more, dashing hope again. Worst by far were the brutal days when the wind failed entirely, and all they could do was strip the sails from the masts and lie under them from dawn until dusk, abandoning the boat to the mercy of the waves. Their minds, said Chase, were now “dark, gloomy and confused.” One night, when they came upon a shoal of whales, the men cowered for hours in the bottom of the boat, terrified of what a few months before they had hunted in that very craft. Yet Chase refused to let his men give up. Again and again he pleaded with them to trust their own efforts, keep faith in God’s providence, and fight against despair. These pleadings probably helped, for by now all that kept the men alive was a vestige of the will not to die.

Proof of that came on January 20 when Richard Peterson, a black man, quietly told Chase that he would henceforth forgo his rations. He had, said Chase, “made up his mind to die rather than endure further misery.” After assuring Chase that he had made his peace with himself and his Maker, Peterson, a quiet, religious man, calmly lay back in the boat. “In a few minutes he became speechless. The breath appeared to be leaving his body without producing the least pain, and at four o’clock he was gone. ” The will not to live had brought death within hours. The next day Peterson’s four comrades buried him at sea. They were now, according to Chase’s reckoning, 1,300 miles from Juan Fernandez, 1,600 miles from Chile, in 35° south latitude.

On the strength of one and a half ounces of daily bread and the fortitude of a twenty-three-year-old leader, the will to live remained intact for several days more in Chase’s boat, although it was not until January 28 that a favoring wind at last began to blow strong and steadily. It had come, it seemed, too late. On the morning of February 7, Chase’s men had but three days of food left—twelve mouthfuls of bread—and several hundred miles still to go. “Our sufferings were now drawing to a close; a terrible death appeared shortly to await us. ” That morning Isaac Cole told Chase that all was “dark” in his mind, “not a single ray of hope was left for him to dwell upon. ” Chase, as always, tried to buoy him up, although what it was that still buoyed Chase, “God alone knows,” as he himself put it.

Once

Dark thoughts now preyed on the minds of the three survivors. “We knew not then to whose lot it would fall next, either to die or be shot and eaten like the poor wretch we had just dispatched.” The fate they so dreaded when they had turned their backs on Tahiti was now threatening each of them.

Between the twenty-fifth and twenty-eighth of January three more men died, and their flesh, too, was shared between the boats. Then, on the night of January 28, a storm separated Captain Pollard’s group from the three men still alive in the other boat. They were never heard from again. In the captain’s boat there were now four starving men: the captain, a young cabin boy named Owen Coffin, bearer of one of Nantucket’s most illustrious names, a Portuguese named Barzillai Ray, and a third Nantucket man, Charles Ramsdell. On February 1 they reached

With the flesh of their comrades all eaten, said Pollard, “we looked at each other with horrid thoughts in our minds, but we held our tongues.… I am sure we loved one another as brothers all the time; yet our looks told plainly what must be done. ” By lot, a victim would be chosen and shot for his flesh. By lot, his executioner, too, would be chosen. Ramsdell drew the executioner’s straw. When the little cabin boy drew the victim’s, “I started forward and cried out, ‘My lad, my lad, if you don’t like your lot, I’ll shoot the first man that touches you.’ The poor, emaciated boy hesitated for a moment or two, then, quietly laying his head down upon the gunwale of the boat, he said, ‘I like it as well as any other.’ He was soon dispatched and nothing of him left.” To his clerical listeners Pollard then cried out in a passion: “I can tell you no more. My head is on fire at the recollection. I hardly know what I say.”

That was February 1 on Captain Pollard’s whaleboat. On February 11 Ray succumbed to starvation, and his flesh, too, prolonged the lives of his two survivors, Pollard and Ramsdell. By now the two horror-haunted whaleboats of the Essex —the captain’s and the first mate’s—were sailing on a perfectly parallel course, with Chase’s boat some 300 miles farther north. On both boats the suffering and the horrors appeared to have been borne in vain. On February 18 three men were still alive on Owen Chase’s boat, but all their carefully hoarded food was gone, and Chile was still 300 miles away.

That morning Chase was dozing at the rudder while seventeen-year-old Thomas Nicholson lay in the bottom of the boat covered with a canvas and praying for death. It would have come to him swiftly enough had not the third man aboard suddenly cried out: “There’s a sail!” Instantly awake, Chase struggled to his feet to gaze “in a state of abstraction and ecstasy upon the blessed vision of a vessel seven miles off.” It was the brig Indian out of London. A few more miles of tense sailing and the hideous ordeal was over for Chase and his comrades. They had been eighty-three days at sea and had voyaged an incredible 4,500 miles in an open boat. Moreover, in a superb feat of navigation, Chase had brought his men from Henderson’s Island to within a few miles of Juan Fernandez. Five days later, Captain Pollard and Charles Ramsdell, too, were rescued at sea, 100 miles

In time, all four of Captain Pollard’s surviving crewmen were to command whaleships of their own, enjoy prosperity, and live long lives. Of their brutal ordeal they gave few outward signs, although Chase in later years became prey to a harmless compulsion. Every time he returned to Nantucket, he would go up to the attic of his house and stow away crackers and bits of food. Only Captain Pollard himself was dogged by misfortune. When he returned to Nantucket in 1825, after his second ship was wrecked on a Pacific reef, the spirit that had sustained him throughout the ordeal of the Essex seemed to have been snuffed out forever.

Retiring from the sea, he became at age thirty-six a humble nightwatchman on the island—meek, mute, yet strangely at peace. After his anguished lapse before the two English missionaries, George Pollard never again spoke about his Essex ordeal. Nor did the people of Nantucket care to hear of it. In that tight-knit community, where ties of kinship bound so many whaling families together, the fate of the Essex and its men touched too many lives too intimately to bear repeating. The veil of silence was still intact some eighty years later when a young Nantucket girl asked the aged daughter of an Essex survivor some questions about what had happened so long ago and so far away. The old woman rose to her feet and said with quiet firmness, “Miss Molly, here we never mention the Essex.”