Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

February/March 1981 | Volume 32, Issue 2

Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

February/March 1981 | Volume 32, Issue 2

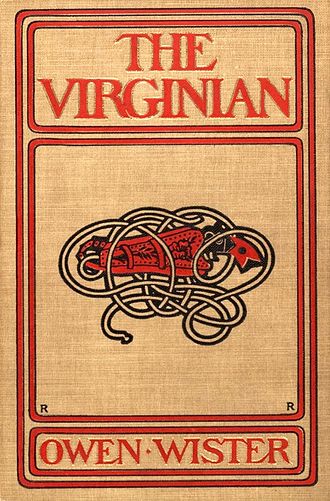

We think of the cowboy and of the open range as part and parcel of the American legend that spread eastward from the West during the nineteenth century. Yet the legend had not become national until the early twentieth century, and its principal literary architect was an Easterner to the core. The crucial event in its popular dissemination was The Virginian, a novel written by Owen Wister and published in 1902. Its success was instantaneous, large-scale, and enduring. Within four months it sold fifty thousand copies, and one hundred thousand in a little more than a year; it was reprinted fifteen times within seven months and nineteen times within the following eight years; fifteen more reprintings followed within a quarter of a century. Such different men as Theodore Roosevelt and Henry James praised it. In 1904 The Virginian was made into a play; in 1914 into a silent movie; in 1929 into a talking movie, with the then largely unknown Gary Cooper as the hero and Walter Huston as the villain; the movie launched Cooper’s career.

The Virginian was, thus, an event in the history of American literature—but even more, an event in the history of American imagination. It fixed the framework of the Western story for good, certainly for the better part of the twentieth century: for it was within this frame that most Western stories, whether in print, on screen, or on television, were to be set again and again and again.

The story of The Virginian is simple, and it may be summed up as follows: At the outset the narrator (very obviously Wister himself) meets “a slim young giant, more beautiful than pictures.” He is a “cow-boy,” from “old Virginia” (except for one passing instance, we never learn his name), sent to meet the narrator at the railroad and to accompany him to the ranch of the latter’s friend, Judge Henry. Immediately he impresses the narrator with his bearing, his manner of speech, and his courage. There are various incidents demonstrating these characteristics of the Virginian, including—again very early in the story—his first encounter with the villain, Trampas, at the poker table. The Virginian is slow calling a bet. “Your bet, you son-of-a —,” Trampas says. “The Virginian’s pistol came out, and his hand lay on the table, holding it unaimed.” (In the 1929 movie Cooper pushed it into the villain’s stomach.) The Virginian drawls the famous phrase “When you call me that, smile !” Trampas is silent. Then and there their mutual hatred begins. They confront each other several times during the hundreds of pages that follow.