Authors:

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

August/September 1979 | Volume 30, Issue 5

Authors: John Egerton

Historic Era:

Historic Theme:

Subject:

August/September 1979 | Volume 30, Issue 5

The Reverend L. Francis Griffin sat in a metal folding chair in the basement assembly hall of the First Baptist Church in Farmville, Virginia. His modified Afro, bushy eyebrows, and Vandyke beard were flecked with gray. Behind horn-rimmed glasses, his brown eyes seemed to suggest a mixture of attentiveness and fatigue, of serenity and sadness.

He had been the pastor of First Baptist for nearly half of his sixty-one years. In the assembly hall where he sat, he had conducted countless hundreds of meetings: with members of his congregation, church committees, Sunday-school children—and with striking high school students, civil rights groups, attorneys, the press. Twenty years ago the Reverend Griffin was the central figure in a long-running effort to achieve desegregation and racial equality for the black citizens of Farmville and Prince Edward County. Now, in the quiet repose of a weekday morning, he pondered a visitor’s question for a moment before responding in a baritone voice rich with the accent and cadence of Southside Virginia. “Who won? It depends on how you look at it. If you’re talking about integration in a local sense, then it could be said that the whites won, because there’s still a lot of segregation and inequality around here. But if you’re looking at it on a national scale, I’d say we won a victory. I believe you could say the black people of Prince Edward County saved the public schools in the South, particularly in Virginia. Had we given in, I think perhaps massive resistance might have become the order of the day throughout the South. So in that sense, we won a tremendous victory.”

In his office at the Farmville Herald, barely two blocks from Griffin’s Main Street church, publisher J. Barrye Wall, Sr., recalled Prince Edward County’s crucible of the 1950’s with considerable reluctance. Too much had been said and written about it, he asserted firmly: “Accounts in the national press were all so one-sided. It was a long time ago, and I don’t have the time or the interest to look back. I don’t want to go into it any further.”

Barrye Wall is eighty years old, a portly man with white hair and friendly blue eyes. He is a Southern gentleman in the classic mold—formal, courtly, unfailingly polite. Being reminded of an earlier time of discord did not please him, and he searched carefully for proper words

And so, twenty-eight years after the beginning of a school-desegregation controversy in Prince Edward County that attracted national attention and resulted in one of the most significant Supreme Court decisions of all time, it is still unclear exactly who won what. L. Francis Griffin and J. Barrye Wall were principal figures in that conflict—personal symbols of diametrically opposed philosophies. For all their differences (and they are many, and vast), the two men brought some common characteristics—pride, confidence, determination, stubbornness—to what has been aptly labeled “a gentlemen’s fight.” They inspired and influenced large followings—Griffin with the power of his voice, Wall with the power of his press. Now, in retrospect, they speak with ambivalence about the winners and losers, talk instead of “stalemate” and “cold war” and “peaceful coexistence” and “unsettled issues”—and they are not alone.

Melancholy echoes of the Civil War linger in the recesses of private thought about the past quarter of a century of life in Prince Edward County. Farmville, the county seat, was on Robert E. Lee’s route of retreat in 1865, and Appomattox is just twenty-five miles away to the west. Now as then, blacks ponder the meaning of a “victory” that has borne meager fruit, and whites reflect upon a “defeat” that has left attitudes unaltered, lessons unlearned.

Of all the battlegrounds in the struggle for civil rights and racial equality in the South in the nineteen fifties and sixties, none seemed more unlikely—or in the end more inexplicable—than Prince Edward County. It was a conservative rural jurisdiction populated mainly by small-acreage farmers (slightly more of them white than black), and its Old South traditions of white paternalism and black deference seemed to have survived intact from the nineteenth century. Lacking a history of either radicalism or violence—those being considered forms of extreme behavior unbecoming well-mannered people—the county seemed incapable of producing a wellspring of black demands for equality or a massive white counterforce of reaction and resistance.

But consider what actually happened in Prince Edward County, in startling contradiction to its past:

In 1951, almost a decade before organized student protests became a weapon in the civil rights movement, a group of juniors and seniors in the county’s black high school in Farmville led a strike in protest against educational inequities. Virtually the entire student body joined in the walkout, keeping the school closed for

Shortly thereafter, black students and adults in the county accepted the aid of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in a lawsuit challenging segregation in the public schools. Three years later, when the case reached the U.S. Supreme Court on appeal, it was incorporated with similar ones from Kansas and elsewhere and made the basis for the court’s famous Brown v. Board of Education decision declaring school-segregation laws unconstitutional.

In 1959, after the state of Virginia had tried and failed to meet the Supreme Court ruling with “massive resistance” —a strategy bordering on open defiance of the federal government—the white elected officials of Prince Edward County shut down their public schools and kept them closed for five years rather than permit white and black children to attend class together. A makeshift private school network was set up to accommodate white students and teachers; all blacks were locked out.

Now, twenty years after it closed its schools and fifteen years after it was compelled by the Supreme Court order to reopen them, Prince Edward County clings stubbornly to school segregation. Most of its white pupils attend the all-white private academy, which has become a permanent fixture in the community, and all of its black students are in the public schools with a minority (25 per cent) of whites. Thus, even as desegregation has become more the rule than the exception in the schools of the South—and more widely established there than in the rest of the country—most Prince Edward whites have continued on their charted course of racial separation. Only in that—and in a general avoidance of violence—has the county behaved consistently with its past.

By the time it was chartered in 1754 and named for the grandson of the reigning king of England, Prince Edward County already had formed the basic patterns of a way of life that would continue in recognizable form through nationhood, civil war, reconstruction, and twentieth-century modernism. It had a tobacco-based agricultural economy, sharp social-class divisions among whites, black subservience, and a general lack of enthusiasm for the notion of education for the masses. Before and after the Civil War, it gave its upper-class whites classical education in home-based private schools, and provided little else for white children of lesser means and nothing at all for blacks until 1870, when some segregated primary schools were opened for both races. The first public high school for whites wasn’t built until the turn of the century, and it was nearly forty years after that before black students could complete twelve years of schooling.

The Robert R. Moton High School, named for a Prince Edward County native who had succeeded Booker T. Washington as president of Tuskegee Institute,

The principle of “separate but equal” facilities and opportunities for whites and blacks had been set down by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1896, but in the states of the South equality never really had been considered, much less achieved, and Prince Edward County was no exception. Moton High School was in no way equal to the high school facilities provided for white students, and the tar-paper outbuildings only served to accentuate the inequality. From time to time there was talk of a new high school for blacks, and the Moton Parent-Teacher Association regularly petitioned the county school board for improvements. But by the beginning of 1951, the board had taken no action on the matter.

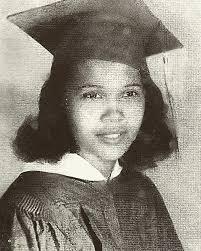

That’s when a sixteen-year-old member of the Moton junior class, Barbara Rose Johns, brought together a small group of her classmates and planned the strike that set in motion thirteen years of conflict, and changed the pattern of white-black relations in Prince Edward County.

On the morning of April 23,1951, the 450 students of Moton High were called to the auditorium, there to be met by Barbara Johns and her companions. The two dozen members of the faculty were asked to return to their classrooms, and reluctantly did so; the school principal was away from the building, responding to an anonymous phone message that two of his students were in trouble at the Farmville bus station.

Quickly, the case for a protest strike was put before the student body: their school was grossly inadequate and unequal, their education was being severely shortchanged as a result, and they should walk out together and stay out until county officials promised them a new school. Protest signs were stored and waiting (“We want a new school or none at all” and “Down with the tar-paper shacks”), and the mass of students rose cheering, took up the signs, and marched out. The strike was on.

The student leaders made two telephone calls that afternoon. One was to the Reverend L. Francis Griffin at his church in Farmville; the other was to the Richmond law office of Spottswood Robinson and Oliver Hill, attorneys for the NAACP. Two days later, in the assembly hall of First Baptist Church, the lawyers and Griffin met with a delegation of students, and the following night, an estimated 1,000 students and parents crammed into the Moton High auditorium to hear and approve, with only a few dissenting voices, a plan for legal action—not just to obtain equal educational facilities, but

White reaction was by stages disbelieving, confused, alarmed, resentful. There were meetings with the student leaders, letters to parents, promises of an all-out effort to secure funds for a new school, charges that the principal of Moton and others (including Griffin) had masterminded the strike. After the school board rejected a petition from the NAACP attorneys calling for desegregation of the education system, the petition promptly was taken into federal court, and the black students returned to school to await the results.

It proved to be a long wait. M. Boyd Jones, the Moton principal, was fired at the end of the year by the school board. The family of Barbara Johns, concerned for her safety, sent her for her senior year to Montgomery, Alabama, where she lived with her uncle, the Reverend Vernon Johns, an expatriate Prince Edward Countian (and predecessor of Martin Luther King, Jr., in the pastorate of Montgomery’s Dexter Avenue Baptist Church). Pressure to abandon the lawsuit was brought to bear upon many blacks in Prince Edward County, including some in Francis Griffin’s church, causing him to put his job on the line by calling for a vote of confidence (and getting it, almost unanimously). Local and state officials, hoping to blunt the desegregation suit by making “separate but equal” a reality, came up with over $800,000 and quickly went to work building a new Moton High School. The months became years. The NAACP lost its case, and appealed. Finally, three years after Barbara Johns and her young allies had raised the issue of discrimination and inequity, the U.S. Supreme Court sought to settle it.

“We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place,” a unanimous court declared in Brown v. Board of Education on May 17, 1954. “Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”

But school desegregation—in Prince Edward County, the South, and the nation—was still a long way from reality.

During the fall of 1954, J. Barrye Wall of the Farmville Herald and a local businessman named Robert B. Crawford became principal figures in the creation of a legal-political-action organization called Defenders of State Sovereignty and Individual Liberties. With strong backing from Virginia’s senior U.S. senator, Harry F. Byrd, and other leading politicians, the group soon built up a membership of several thousand persons across the state. The Defenders also gained quick control of the political machinery in Prince Edward County, and in the spring of 1955 persuaded the county board of supervisors and the leaders of the white parent-teacher association in the county to make plans for a shutdown of the public school system, and the creation of a segregated private school network for white children.

In truth, little persuasion was necessary. White public sentiment had

In Congress Senator Byrd and Virginia Congressman Howard W. Smith introduced the Southern Manifesto in 1956, and used that document of defiance against the Supreme Court’s Brown decision to erect an almost solid wall of resistance across the South. And in the state capitol at Richmond, the Byrd machine—with ideas and encouragement from Richmond’s News Leader editor James Jackson Kilpatrick—developed a plan of “massive resistance” against the authority of the federal government.

As court orders implementing the Brown decision were handed down across the state in 1958, Governor J. Lindsay Almond followed the massive resistance plan and ordered the closing of some schools in Norfolk, Charlottesville, and Front Royal; but the courts quickly struck down the state laws upon which the strategy of defiance was based. Against the angry objection of Byrd, Governor Almond capitulated rather than risk being jailed for contempt of court, and massive resistance died a quick death.

Meanwhile, Prince Edward County officials, still determined to close their schools rather than desegregate them, continued to wait for the dreaded implementation order they knew was inevitable. Complex legal maneuvers had kept their case tied up in the lower federal courts since the Brown ruling. Finally, in 1959, all appeals on the particulars of implementation were exhausted, and schools were ordered desegregated with the beginning of the fall term. The Prince Edward supervisors, true to their word, promptly cut off all funds to the school system and shut it down. Even as Virginia’s strategy of recalcitrance was being shattered and token desegregation was beginning to take place in a few schools across the state, little Prince Edward County prepared to go its chosen way alone, without regard for the consequences.

When September of 1959 arrived, almost all the 1,500 white pupils in the county were enrolled in Prince Edward Academy, the new entity which was holding classes in sixteen temporary locations. They had the same white teachers and administrators as before, the staff of nearly 70 having moved virtually intact from the public payroll to the private one. For the 1,700 black students and approximately 25 teachers, there were no classes, no jobs, no schools.

For all practical purposes, the Prince Edward County government, Prince Edward Academy, and the local Defenders of State Sovereignty and Individual Liberties were dominated by the same people. Throughout the more than eight years of turmoil, the whites never broke

Among blacks, public support of desegregation also was muted. Only the Reverend Mr. Griffin, whose livelihood was beyond the reach of the white establishment, was consistently outspoken. The NAACP, of which Griffin was both a local and state leader, continued its efforts in the federal courts to win desegregation and equal educational opportunity for Prince Edward County blacks, but the legal proceedings were agonizingly slow. The beginning of the private school program for whites seemed to suggest to everyone that a long stalemate was at hand, and as that realization sank in, the various parties became, if anything, more determined and uncompromising than ever.

In the fall of 1959 a group of white segregationists offered to set up a private school program for blacks, ostensibly in response to the plight of idle students and teachers. Most blacks were suspicious of the idea, however, seeing it as a cynical ploy to legitimize segregation, and in the end only one application from a black child was received by the sponsors.

Since the state legislators had set up tuition grants for students attending private schools, the Prince Edward segregationists may have wanted a private school for blacks in order to demonstrate that the tuition grants were available to both races and thus nondiscriminatory. Furthermore, the whites badly needed school buildings for their academy, and there was some speculation that if both whites and blacks had private schools, the padlocked facilities of the public system might somehow be reopened to accommodate them. A dispute over that issue in 1960 led to the only serious split between whites in the community during the entire school crisis. In the opinion of Lester E. Andrews, Sr., chairman of the public school board, it was imperative that the public schools be reopened as quickly as possible. Two former chairmen and close friends of Andrews, B. Calvin Bass and Maurice Large, shared that view. But in the leadership of the private academy there appeared to be a consensus that public schools in the county had been abandoned for good. Neither group favored integration, of course—but the Andrews faction believed that it would be economically disastrous for the county to try to function permanently without a public school system, while the academy backers were willing, even eager, to follow that path.

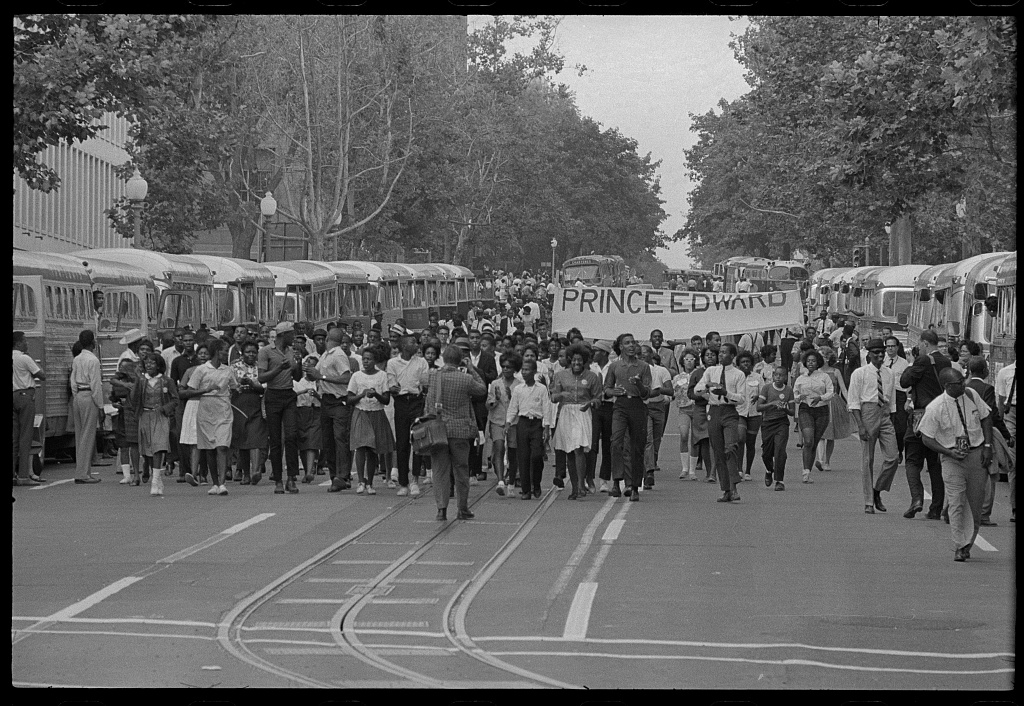

But social ostracism and pressure against the compromisers—derisively dubbed the “Bush League”—grew quickly in the white community. In short order, they abandoned their efforts, and the only sign of serious dissent ever to arise in the school crisis faded and died as quickly as it had arisen. Four more years of closed public schools and dreary stalemate lay ahead for Prince Edward County. Over the years, a number of national groups and organizations tried with varying degrees of success to assist the black children who were locked out of the Prince Edward County schools. The NAACP, the National Council of Negro Women, the American Friends Service Committee, Kittrell College in North Carolina, and numerous others offered assistance. Some students were sent away to schools in other communities and states; some got a little help in makeshift centers set up to operate part-time in the county; some were aided by summer-school programs organized by groups of teachers and others from outside the community. But most of the children—by one estimate, at least 1,100—received virtually no schooling during most of the five-year shutdown. Carlton Terry, one of the fortunate few to be educated elsewhere under the sponsorship of the American Friends Service Committee, called the Prince Edward black adolescents of the 1959—64 period “the crippled generation… [a] generation left lame.” With assistance from officials in the Kennedy administration, private funds were raised to set up a “free school” for black students in the county in 1963. Colgate W. Darden, Jr., a former governor of Virginia and former president of the University of Virginia, was named chairman of the private body’s board of trustees, and Neil V. Sullivan, a well-known public school educator, was brought in as director. Prior to the opening of the free school program in four old “black” public school buildings, a hot summer of demonstrations and discord in Farmville had raised for the first time the threat of widespread violence in the county. Prince Edward was by then a beleaguered community, and a wounded one; its troubles had been told to the nation by television and the press, and in the growing struggle for civil rights that was quickly enveloping the South, it seemed near to becoming a battleground of major importance. One way or another, the stalemate there appeared certain to be broken. During 1963—64, a few fragile seeds of hope took root in the county. The summer demonstrations had ended without disastrous results, the protesters who had come in from other places departed, and a

And at long last, in the summer of 1964, the U.S. Supreme Court concluded once and for all that, in the interest of equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Constitution, Prince Edward County had to maintain a public school system, and that the county’s public officials could be forced, if necessary, to appropriate funds to that end. At a cost beyond measure, the county and the state of Virginia had fought in the courts to prevent that conclusion for thirteen years; in the end, they submitted quietly, and the public schools were reopened in September. The free schools that had operated for one year went out of business. Fewer than a dozen white students and approximately 1,700 blacks enrolled in the “new” Prince Edward County public schools. The number of blacks in school was about the same as in 1959, before the schools were closed—but they were not, of course, all the same children, and it would prove virtually impossible to determine exactly how many had had their education terminated permanently (the total almost certainly ran into the hundreds). As for white children, the commonly expressed belief that they had not been affected adversely by the school closings appeared not to be borne out by the facts: in the eight years prior to 1959, white enrollment in the county grew by 18 per cent; by 1964, the total (i.e., the enrollment at Prince Edward Academy) had fallen by about 20 per cent, and no clear accounting for the loss has ever been made. “People feared the worst,” said James M. Anderson, Jr., the Prince Edward County superintendent of schools, I “but things were never as bad as they were thought to be. There’s great potential here, and we’re making real progress.” In 1979, fifteen years after the schools were reopened, Anderson counted nearly 600 whites and a stable total of 1,700 blacks in the public school enrollment. “When I came here in 1972,” he said, “I was told we would never reach 20 per cent white. We’re at about 25 per cent now.” The “new” Moton High School, erected after the strike in the early 1950’s now is called Prince Edward County

The headmaster at Prince Edward Academy is Robert T. Redd. He has been an administrator and teacher at the school for all of its twenty years. His office is in a building adjoining the academy’s sixty-classroom facility, built in 1961. “The papers tried to crucify us,” he said. “They called us a fly-by-night operation, said we wouldn’t last a year. But we’ve proved them wrong. We’ve shown that we can deliver excellence in education under a controlled environment. Eighty per cent of our graduates go on to college or some kind of post—high school education—and they’re going to highquality institutions like the University of Virginia and Virginia Tech, and doing well there.” Admission to the academy is not selective, Redd said, “except that we avoid known discipline problems.” The school has enrolled nonwhite students he added—Koreans, Chinese, American Indians, Spanish—but no blacks: “None have ever applied. We have no written policy on that. If they came, I suppose we would handle them the same as we do all the others.” According to Redd, Prince Edward Academy’s enrollment was stabilized at about 1,200 for a number of years, before tapering off over the past five years to the present level of about 1,000. Its tuition has increased gradually but steadily, $850 for high school students and $800 for the lower grades. Teacher salaries also have risen, from less than $4,000 a year in the beginning to an average of about $8,000 now. “Our pay scale isn’t as high as the public schools,” the headmaster said, “but we don’t have any trouble getting teachers. All of our classroom teachers are certified, onethird of them have master’s degrees—and this year, we had about a hundred applications for two vacancies. The best teachers want to come here because we don’t have any discipline problems. We run a tight ship.” The relationship between Prince Edward Academy and the public schools of Prince Edward County is not unfriendly, both sides agree—not close, but not hostile either—and while it might be stretching a point to say they wish each other well, it is certainly safe to assume that they watch each other closely, and with keen interest. All the heat of the nineteen fifties and early sixties in Prince Edward County has long since burned out. The people have adjusted, adapted—some with relief, others with resignation—to the new arrangement. Some are pleased with the

Lester E. Andrews, Sr., a one-time chairman of the county school board, now serves on an electoral commission that appoints new members to the board; he also serves as a member of Prince Edward Academy’s governing body. When he resigned the school board chairmanship in 1960 rather than vote to sell school property, Andrews lost some friends. Recalling that, he said: “People didn’t understand what we were trying to do. We were trying to keep the black schools open. I have no regrets about my role in it—or about the outcome. The blacks lost five years of school, and they were hurt immensely by that—but now, they’re probably getting a better education. The academy was hard pressed to begin with, but whites have also ended up getting a better education than before. In a way, you could say we’ve got pretty much what we had before, only better.” Gordon Moss, the history professor at Longwood College who almost alone among Farmville whites opposed not only the closing of the schools but also segregation itself, is less sanguine today. In 1968 he retired from teaching but stayed in Farmville; he lives there still, a seventy-eight-year-old former scholar with a still-active mind and a Sandburgian shock of white hair. His assessment of the outcome of the Prince Edward County school closings is quietly, matter-of-factly negative: “Most of the blacks got no education at all, and have grown up uneducated. Some went away to school, and profited greatly from the experience, but the vast majority were simply lost. I’d say the white segregationists won. They have to obey the letter of the law now, but not the spirit—and they don’t. There is no longer total segregation, but the whites still get what they want. As long as they can raise enough money to keep their academy going strong, they’ve won. Not many lessons have been learned. I’m afraid we accomplished very little.” But of all the people who figured prominently in the Prince Edward County conflict, Leslie Francis Griffin could be said to have been the central character. Many whites—and not a few blacks—saw him as a radical disrupter of the peace and perhaps the instigator of the student strike and the NAACP lawsuit. The NAACP lawyers and all those who tried in one way or another to bring pressure to bear from outside the community found it necessary to reckon with him. Sitting in the two-story brick church his father had pastured before him—a structure that had served as a hospital for Union soldiers during the Civil War and

The youngest of the Griffin children is a student at Prince Edward County High School now, where Mrs. Griffin teaches. The older children are all grown and gone; one of them graduated from Harvard and presently is pursuing doctoral study there. “They missed four years of school, the same as most of the others,” Griffin said. “As long as any black child was without education, I couldn’t in good conscience let mine go off to school somewhere else. After the schools reopened, we did send two of them away. It’s hard to say how much damage was done to children here by the closing of the schools, but many had tremendous gaps in their learning after they returned, and many others never continued school at all.” The quality of the public schools now, in Griffin’s opinion, “is comparable with that of schools elsewhere in Southside Virginia—and I don’t know if that’s saying a lot. I think they’re working up to standard, and I hope they’ll continue to improve. But it’s still a question of money and politics. All American schools seem to be in trouble—and these are no different.” The Prince Edward Academy, he added, “is pretty much like it has always been, and I don’t see anything other than economic factors changing that.” The changes he has seen in Prince Edward County since he returned there to live almost thirty years ago have left Francis Griffin with mixed emotions. He has seen black land ownership decline sharply as small-acreage family farming has become virtually impossible to make profitable; at the same time, he has seen some industry come into the community, with the result that many blacks (and whites) have steadier employment and higher incomes than they have ever had before. Some blacks now serve on the county board of supervisors, on the school board, in other offices of government, and in law enforcement—but there are fewer black craftsmen and small-business owners than in previous years. Race relations, too, are both better and the same, he says: “Among young adults, I think things are better—there’s more contact, more pragmatic cooperation. My hope is with those young adults—and of course, there’s always hope for the little ones, even though the continuation of segregated

Of the country’s white men of power, Griffin said: “I see some of them now and then. Some of them have told me they feel what happened was for the best. They may not tell you that, but they’ve told me. A few of them have told me they now see and appreciate what I was trying to do—but I doubt if you could find any who would say, even in private, that they think integration is right. Even now, they would be afraid to be identified with that position.” And what of the future? “Unless something drastic, such as an economic crisis, forces further change,” he said, “I don’t see things being much different in another twenty or twentyfive years than they are now. In essence, there’s a new status quo here. There is no voluntary movement toward greater equality. That’s unfortunate, but it’s true. This is still a battleground, the lines of separation still exist—but the pressures are not such that there will be skirmishes, or all-out fighting. It’s a cold war now, and I look for it to go on.” What of the “young adults” on whom Francis Griffin pins his hopes? Most members of the Moton High School “strike class” of 1951, including Barbara Johns, left the community. One of them, James Samuel Williams, returned to Farmville in 1977 from Buffalo, where as a Baptist minister he directed a ghetto social-action program for nine years. Williams said the school strike and subsequent developments “didn’t end racism and exploitation in Prince Edward County, but they raised people’s consciousness permanently, raised black expectations, gave blacks a sense of personal worth, and taught them the meaning of justice and equality. Reverend Griffin was responsible for that.” The basic problems of Prince Edward County, he added, are the same as before: “Racism, stratification, and competition are dominant here, as they are everywhere else in the country. But I do see some change for the better since I left. We’ve got a better chance to make it than Buffalo, and I’m glad to be back.” Other young adults have begun to manifest a more independent and progressive outlook in the county’s businesses and professions, in government, and especially in politics. The Prince Edward County Democratic party organization, long dominated by conservatives, is now in the hands of a committee carefully balanced with whites and blacks, progressives and conservatives, young and old, male and female. (Women, virtually invisible in the upper

Donald Stuart, a young English professor at Longwood College and the current chairman of the Democratic party, has made clear his position on race. “The rigid segregationist is a dying breed,” he said. “The world is changing. Younger people are coming into this community who don’t have any hang-ups about race. I wouldn’t call them liberal—they’re just color blind. They want everybody to participate—not necessarily for social reasons, but simply because it’s good for business.” Marshall Ellett, a thirty-one-year-old attorney and native of Southside Virginia, is another activist in Prince Edward’s political “youth movement.” A self-described “pragmatist,” he helped to fashion the “exotic coalition” that now bids to become the new voice of political power in the county. He acknowledges that racial inequities still exist. “We’re still paying for the troubles of the past,” he said. “That’s a cross we bear. But we’re trying to pick up the pieces, and though it may take fifteen or twenty years, I think we can solve our racial and economic and educational problems.” Finally, there is James Edward Ghee, Jr. He was born and raised in Prince Edward County. When the schools were closed in 1959, he was about to enter the ninth grade at Moton High School. He was out of school for two years, a member of the “lost generation”—but he was not lost. He was one of sixty-seven children sent to schools in other parts of the country by the American Friends Service Committee. Ghee attended high school for four years in Iowa City, Iowa, and went on to graduate from the University of Iowa in 1969. Returning to his home state, he was admitted to the University of Virginia law school. After earning his degree there and gaining three years of experience elsewhere, he returned to Farmville in 1975. He is the only black attorney in private practice between Lynchburg and Richmond, and the first ever to practice in Prince Edward County. “I think I always knew I was coming back,” he said. “I knew there was a need—not just for a lawyer, but for someone who could help as I had been helped. The best way to make a difference with my life, I felt, was to go back home—and it’s a real good feeling to be back.” James Ghee is a principal figure in the group of young adults seeking to reform the county Democratic party. He has a thriving practice on Farmville’s Main Street, representing white as well as black clients. He is near his parents (his father is a laborer, his mother a maid) and near his friends, old and new. “I’m really satisfied here,” he said. “There is a sense of accomplishment, a reason to be optimistic. There has been some change—and there’s more coming. The old traditions and customs are falling. Over time, the younger