Authors:

Historic Era: Era 6: The Development of the Industrial United States (1870-1900)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Spring/Summer 2008 | Volume 58, Issue 4

Authors:

Historic Era: Era 6: The Development of the Industrial United States (1870-1900)

Historic Theme:

Subject:

Spring/Summer 2008 | Volume 58, Issue 4

In his new book, The Telephone Gambit: Chasing Alexander Graham Bell’s Secret, Seth Shulman claims that the famous inventor “was plagued by a secret: he stole the key idea behind the invention of the telephone.”

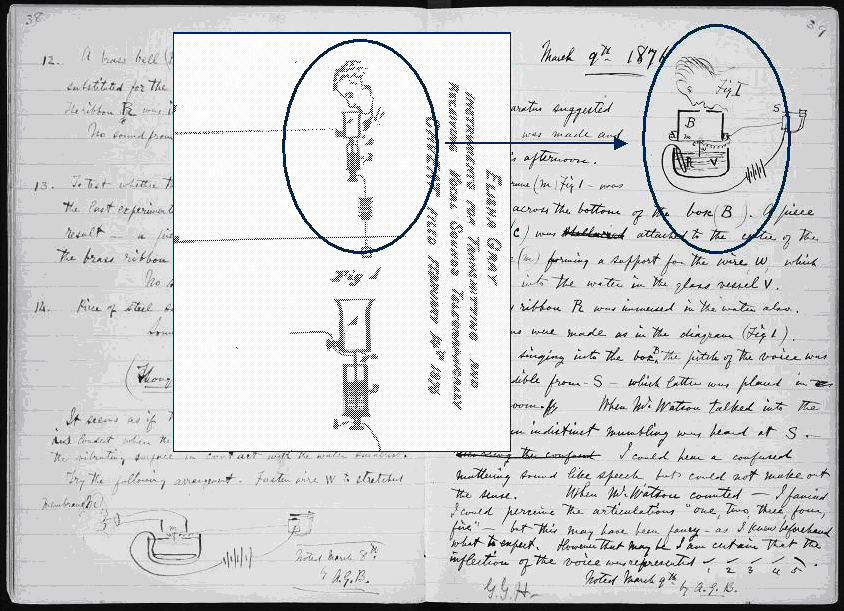

In this well-written, but critically flawed account, Shulman tells the story of his research in the Bell-versus-Gray controversy— the question of who first came up with the key technological innovation for the phone. He digs into archives and discovers a critical page in Bell’s notebook from March 1876, a sketch drawn shortly before the time that Bell uttered the famous phrase, “Mr. Watson, come here; I want to see you.” Shulman claims that the drawing of a liquid transmitter is strikingly similar to the earlier drawing in Elisha Gray’s patent caveat. Shulman’s conclusion is clear: Bell saw the caveat and copied the idea into his notebook. Bell subsequently built the liquid transmitter, which worked, and the rest is history.

Central to Shulman’s argument was his “discovery” of two affidavits written by Zenas Wilber, the clerk in the Patent Office who examined Bell’s application, in which ten years after the fact he claimed the inventor slipped him a $100 bill to reveal Gray’s patent caveat. By now an ill and penniless alcoholic, Wilbur contradicted his earlier testimony that everything was routine in the Bell patent application. Shulman relates how these new documents were discovered in an attic and never played a role in any of the legal challenges to Bell’s claim to the telephone. (authors’ italics)

In fact, these affidavits are far from unknown. They played a central role in the notorious “Pan-Electric Case,” which erupted into the largest scandal of the Grover Cleveland Administration. Wilber’s alleged deathbed confession was not the work of an old man with a burdened conscience, but a carefully crafted legal document written with the help of lawyers working for a company seeking to steal rights to the most lucrative patent ever issued in U.S. history. This dubious testimony has been at the center of a very public debate over the telephone patents for 125 years. It is hard to understand how Shulman could have missed or ignored the question of their credibility.

By 1886, the Bell companies had defended their patents in some 600 court cases, before hundreds of judges in many jurisdictions. Bell never lost a case. Having exhausted all other channels, the only remaining means of attacking the patents was to allege that they had been obtained fraudulently. The founders of Pan-Electric took this course, filing their own patents, which bore a striking resemblance to Bell’s, and then urging the government to have the Bell